随着杀虫剂的广泛应用,环境中残留着大量有机氯、有机磷、拟除虫菊酯和新烟碱类等具有内分泌干扰效应的杀虫剂,对生物体具有显著的生殖和发育毒性[1]。近年来,水体环境中杀虫剂类内分泌干扰物(endocrine disrupting chemicals, EDCs)的检出率和检测浓度越来越高[2],其检出浓度可以高达0.7088 μg·L-1[3],其潜在的生态毒性效应也已经成为热点课题。杀虫剂类EDCs是通过摄入、累积等途径进入生物体,通过与雌激素、雄激素和甲状腺素等激素受体结合、与其他受体结合以及非受体途径干扰体内激素平衡并改变内分泌系统功能[4-5],从而对水生生物的生长发育和存活率具有显著的不良影响。如残留的杀虫剂会干扰溞类的产卵行为,影响其存活率等[6],具有内分泌干扰效应的杀虫剂还会与生物体内的生殖系统、神经系统和免疫系统中不同的内分泌激素受体相结合导致各系统的紊乱,从而影响生物体的表面形态、行为活动、生长繁殖和存活。

水溞是一种广泛存在的淡水浮游动物,其中小型甲壳动物大型溞(Daphnia magna)属于枝角目,由于它具有易于培养、繁殖周期短、对环境条件敏感等特点,是被广泛用作毒理学研究的模式生物之一[7]。在过去的20年里,大量关于杀虫剂对大型溞慢性毒性影响的研究表明,长期暴露于杀虫剂会导致无脊椎动物出现形态异常,生殖改变、产生雄性后代、蜕皮频率异常和基因差异表达的现象[8]。有研究发现大型溞致死现象与杀虫剂的神经毒性密切相关[9],但具体的作用机制仍有待进一步揭示。目前的研究主要集中于杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的急性或慢性毒性,随着组学技术的发展,人们通过应用DNA微阵列分析和高通量测序等技术将大型溞的表型生理变化与基因表达水平联系起来[10],为识别生物标志物和毒性作用途径提供依据,提供了从宏观到微观角度系统分析杀虫剂类EDCs对水生溞类生态毒性的新视角。

由于杀虫剂的作用途径十分复杂,本文旨在根据目前的研究现状总结归纳典型的杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的毒性效应和作用机制。通过繁殖、生长、蜕皮和性别比例等典型生理参数的变化直观反映杀虫剂类EDCs在生理层面对大型溞生长、发育和繁殖的影响,从酶活性变化的角度分析由此造成的氧化应激和神经系统损伤,识别潜在的生物标志物,并在基因表达水平上阐明杀虫剂类EDCs改变的通路,揭示其毒性作用的分子机制,为进行生态环境风险评估和污染物质的管理提供依据。

1 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的急性毒性效应(Acute toxic effects of pesticides EDCs on Daphnia magna)

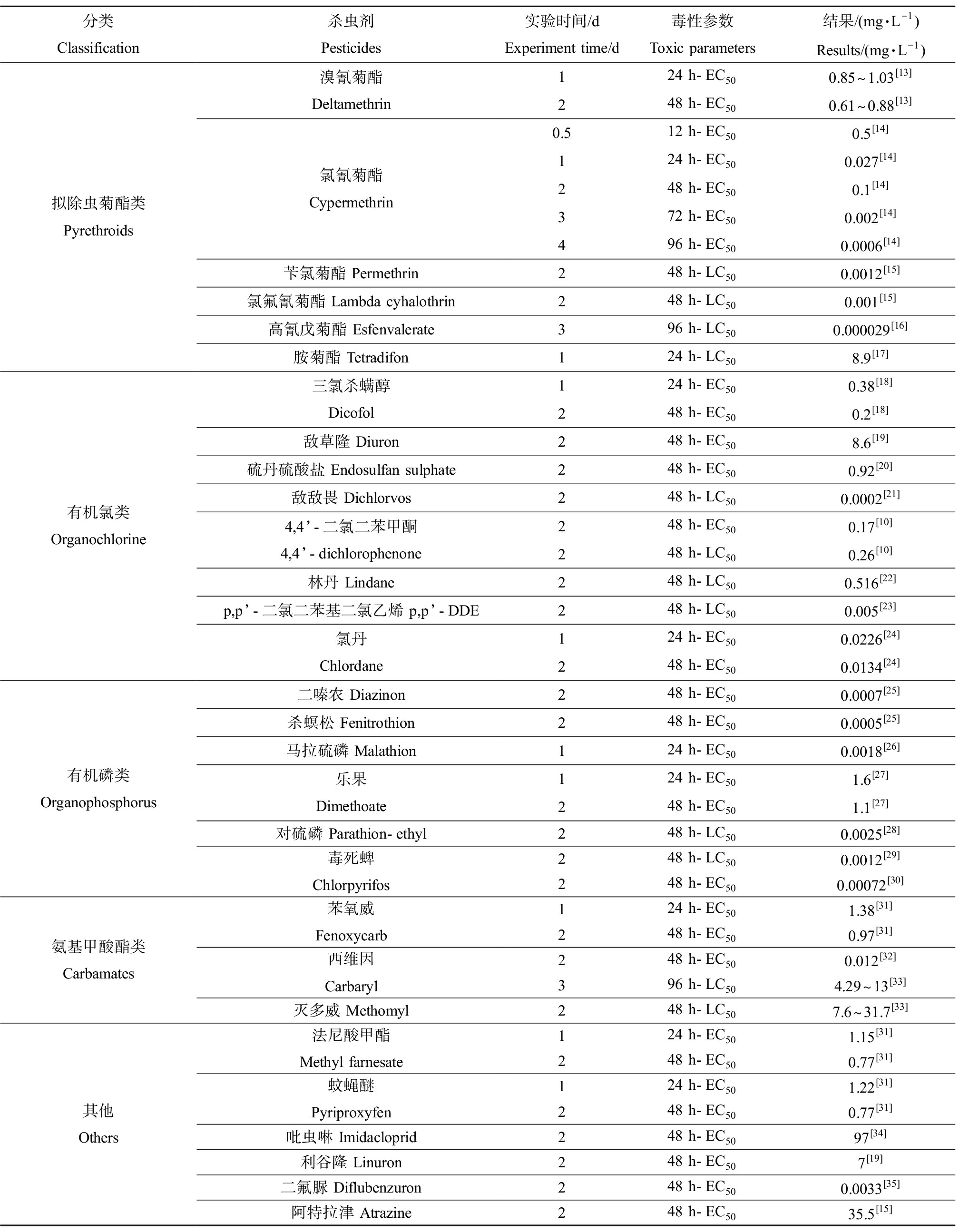

大型溞作为生态毒理学研究的模式生物之一,通常是根据经济合作与发展组织(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD)准则[11]获得的不同杀虫剂类EDCs急性毒性研究结果。通过检索Elsevier Science Direct全文数据库、Springer全文数据库、Web of Science和美国化学学会(American Chemical Society, ACS)数据库,归纳近25年有关淡水无脊椎动物的生态毒理学参数包括:半数效应浓度(concentration for 50% of maximal effect, EC50)、半数致死浓度(lethal concentration for 50%, LC50)[12]等表征参数如表1所示。

对比表1中不同EDCs的急性毒性参数发现,具有保幼激素活性的杀虫剂和有机磷类、拟除虫菊酯类杀虫剂的急性毒性较强,48 h-EC50大多低于10 mg·L-1,表明实际环境浓度下的杀虫剂会对水溞和小型水生动物的健康产生威胁。其中,吡丙醚作为防治公共卫生虫害的杀虫剂,应用广泛。Ginjupalli和Baldwin[36]发现吡丙醚作为保幼激素的类似物,幼龄大型溞对其非常敏感,能显著干扰幼体的生理发育和繁殖,当大型溞暴露于25 ng·L-1吡丙醚时就开始出现发育延缓和卵子的孵化率降低现象,从而导致大型溞死亡率升高和种群密度下降。此外,当大型溞暴露于250 μg·L-1的苯氧威时,水溞胚胎的孵化率会显著降低,在高浓度下会出现完全不孵化现象[37]。这些毒性差异可能是由于不同化学物质的化学性质和环境中的累积量所导致的。由于大部分杀虫剂对大型溞表现出强烈的毒性作用和过量毒性,这不仅仅与疏水性有关,还与极性比表面积、极性、分子体积和氢键碱度有关。这些特征共同表明具有保幼激素活性的杀虫剂与大型溞生物活性大分子之间是基于配体-受体相关的特异性作用发挥毒性的[38]。

表1 典型的杀虫剂类内分泌干扰物(EDCs)对大型溞的急性毒性

Table 1 Acute toxicity of typical pesticides endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) to Daphnia magna

分类Classification杀虫剂Pesticides实验时间/dExperiment time/d毒性参数Toxic parameters结果/(mg·L-1)Results/(mg·L-1)拟除虫菊酯类Pyrethroids溴氰菊酯Deltamethrin氯氰菊酯Cypermethrin苄氯菊酯 Permethrin氯氟氰菊酯 Lambda cyhalothrin高氰戊菊酯 Esfenvalerate胺菊酯 Tetradifon124 h-EC500.85~1.03[13]248 h-EC500.61~0.88[13]0.512 h-EC500.5[14]124 h-EC500.027[14]248 h-EC500.1[14]372 h-EC500.002[14]496 h-EC500.0006[14]248 h-LC500.0012[15]248 h-LC500.001[15]396 h-LC500.000029[16]124 h-LC508.9[17]有机氯类Organochlorine三氯杀螨醇Dicofol敌草隆 Diuron硫丹硫酸盐 Endosulfan sulphate敌敌畏 Dichlorvos4,4’-二氯二苯甲酮4,4’-dichlorophenone林丹 Lindanep,p’-二氯二苯基二氯乙烯 p,p’-DDE氯丹Chlordane124 h-EC500.38[18]248 h-EC500.2[18]248 h-EC508.6[19]248 h-EC500.92[20]248 h-LC500.0002[21]248 h-EC500.17[10]248 h-LC500.26[10]248 h-LC500.516[22]248 h-LC500.005[23]124 h-EC500.0226[24]248 h-EC500.0134[24]有机磷类Organophosphorus二嗪农 Diazinon杀螟松 Fenitrothion马拉硫磷 Malathion乐果Dimethoate对硫磷 Parathion-ethyl毒死蜱Chlorpyrifos248 h-EC500.0007[25]248 h-EC500.0005[25]124 h-EC500.0018[26]124 h-EC501.6[27]248 h-EC501.1[27]248 h-LC500.0025[28]248 h-LC500.0012[29]248 h-EC500.00072[30]氨基甲酸酯类Carbamates苯氧威Fenoxycarb西维因Carbaryl灭多威 Methomyl124 h-EC501.38[31]248 h-EC500.97[31]248 h-EC500.012[32]396 h-LC504.29~13[33]248 h-LC507.6~31.7[33]其他Others法尼酸甲酯Methyl farnesate蚊蝇醚Pyriproxyfen吡虫啉 Imidacloprid利谷隆 Linuron二氟脲 Diflubenzuron阿特拉津 Atrazine124 h-EC501.15[31]248 h-EC500.77[31]124 h-EC501.22[31]248 h-EC500.77[31]248 h-EC5097[34]248 h-EC507[19]248 h-EC500.0033[35]248 h-EC5035.5[15]

注:EC50表示半最大效应浓度,LC50表示半致死浓度。

Note: EC50 means concentration for 50% of maximal effect; LC50 means median lethal concentration.

2 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的慢性毒性效应(Chronic toxic effects of pesticides EDCs on Daphnia magna)

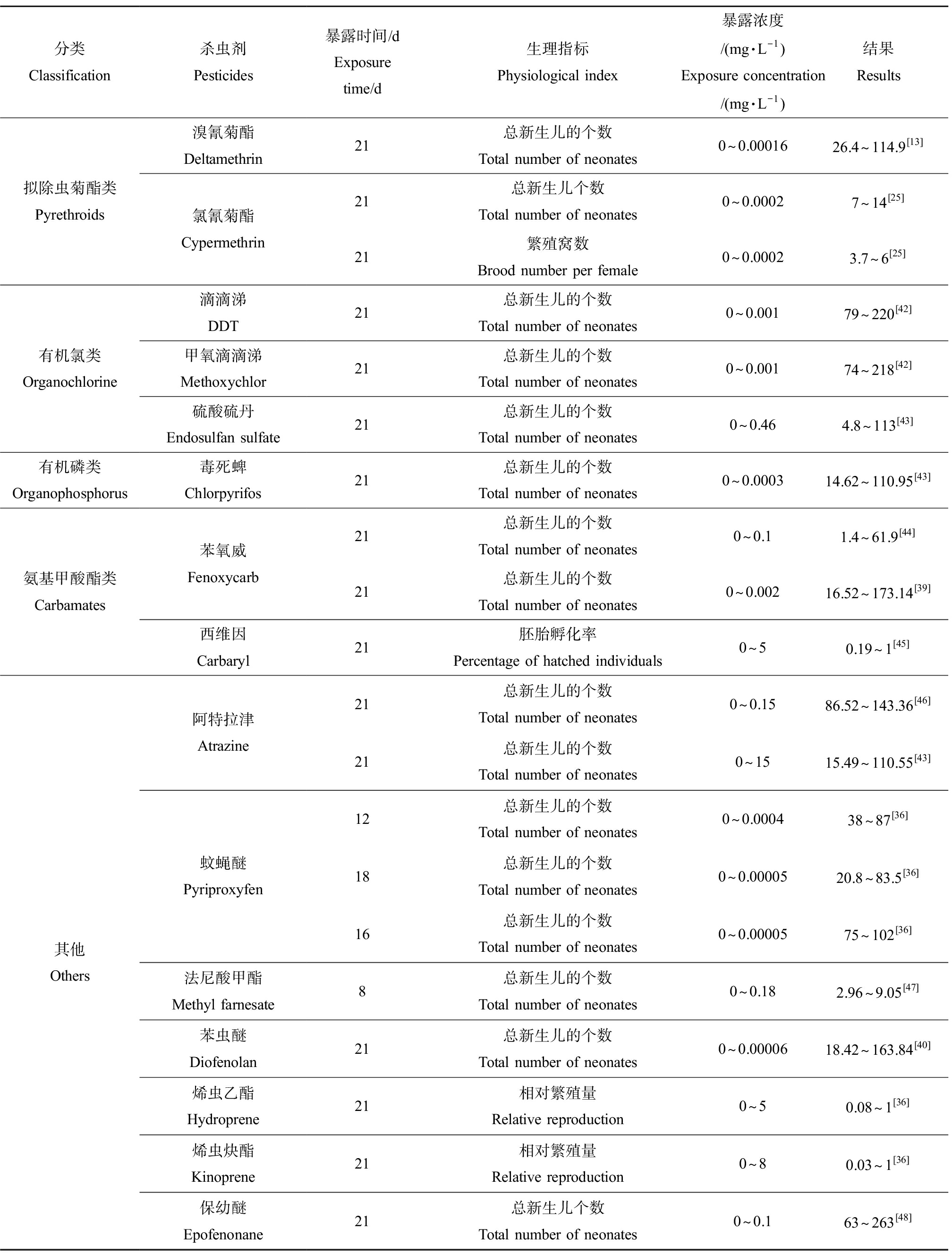

EC50值是用剂量-反应曲线表示不同化学物质的急性毒性,但是由于急性毒性并不能全面反映化学物质对模式生物长时间作用的结果,因此有必要研究更具现实环境意义的慢性毒性实验,从而揭示化学物质的慢性毒性效应。慢性毒性实验是在急性毒性实验的基础上,将水生动物暴露于一系列亚致死浓度的污染物质一定时间后,通过观察水生溞类的生长(体长)、繁殖、蜕皮、畸形率和雌雄比例等的变化研究污染物质通过多种途径对水生生物产生的毒性效应。通过查阅大量文献整理了目前关于模式生物的毒性效应,重点总结了慢性暴露于环境相关浓度的杀虫剂类EDCs后对大型溞不同生理指标的影响。

2.1 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的生长和繁殖的影响

雌性大型溞新生儿的个数作为典型的生理指标之一,可以有效评估杀虫剂类EDCs的生殖毒性。多项研究表明,雌性大型溞新生儿的个数与杀虫剂的浓度呈负相关关系。常见的杀虫剂对大型溞繁殖的抑制效应如表2所示。例如,Oda等[39]将大型溞暴露于0.01 μg·L-1的苯氧威21 d后,雌性大型溞新生儿的个数相较于对照组减少了约85%;当暴露于100 μg·L-1苯氧威21 d后,雌性大型溞几乎不产生后代。Abe等[40]对苯虫醚的研究也发现了类似的结果。这些结果表明,大型溞新生儿的个数是极其敏感的生理指标,能够直观地反映杀虫剂的慢性毒性效应。此外,环境中某些低浓度的固醇类化合物可能会影响水溞的繁殖能力,如有研究发现长期暴露于低浓度的雌二醇后,大型溞的繁殖力降低了25%左右,通过检测体内的卵黄蛋白原浓度验证了该现象是由于内分泌系统紊乱导致的[41]。由此可见,雌性大型溞新生儿的个数可作为杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞生殖毒性的标志指标之一,并可以此来预测其对溞类种群水平的影响。

体长是反映大型溞生长发育速率的一个重要指标,当大型溞暴露于杀虫剂时,其生长速率会受到显著的抑制。有研究者将大型溞慢性暴露于0.01 μg·L-1的苯氧威时发现,其体长相较于对照开始出现显著抑制现象;当暴露浓度达到100 μg·L-1时,其体长相较于对照组减小了1/4[44],由此发现对体长的抑制作用随暴露浓度的增加而增强。氟他胺和氯丹等具有内分泌干扰效应的物质对雌性水溞的生长也有影响,成虫体长与对照相比均有所下降[18]。通过测量体长,从形态学角度反映了化学物质对溞类的毒性效应。

2.2 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞发育畸形的影响

此外,慢性暴露于杀虫剂类EDCs后也会导致大型溞发育畸形。有研究表明杀虫剂能够通过抑制幼虫变形来降低其成虫的存活率,从而起到杀灭虫害的作用。通过整理已有的研究发现,大型溞的发育畸形主要包括弯曲或未伸展的壳棘、肿胀的育雏室、发育不良的第二触角、复眼浑浊、流产卵和四肢发红等现象。例如,Kim等[44]发现大型溞在苯氧威中经过21 d的慢性暴露,出现了不同程度的畸形包括弯曲或未伸展的壳棘、肿胀的育雏室和发育不良的第二触角;当大型溞发育的胚胎暴露于3 μg·L-1的苯氧威时,50%的胚胎会发育畸形如第二触角不完全发育,进一步表明苯氧威会引起生物体功能的紊乱从而导致发育异常。

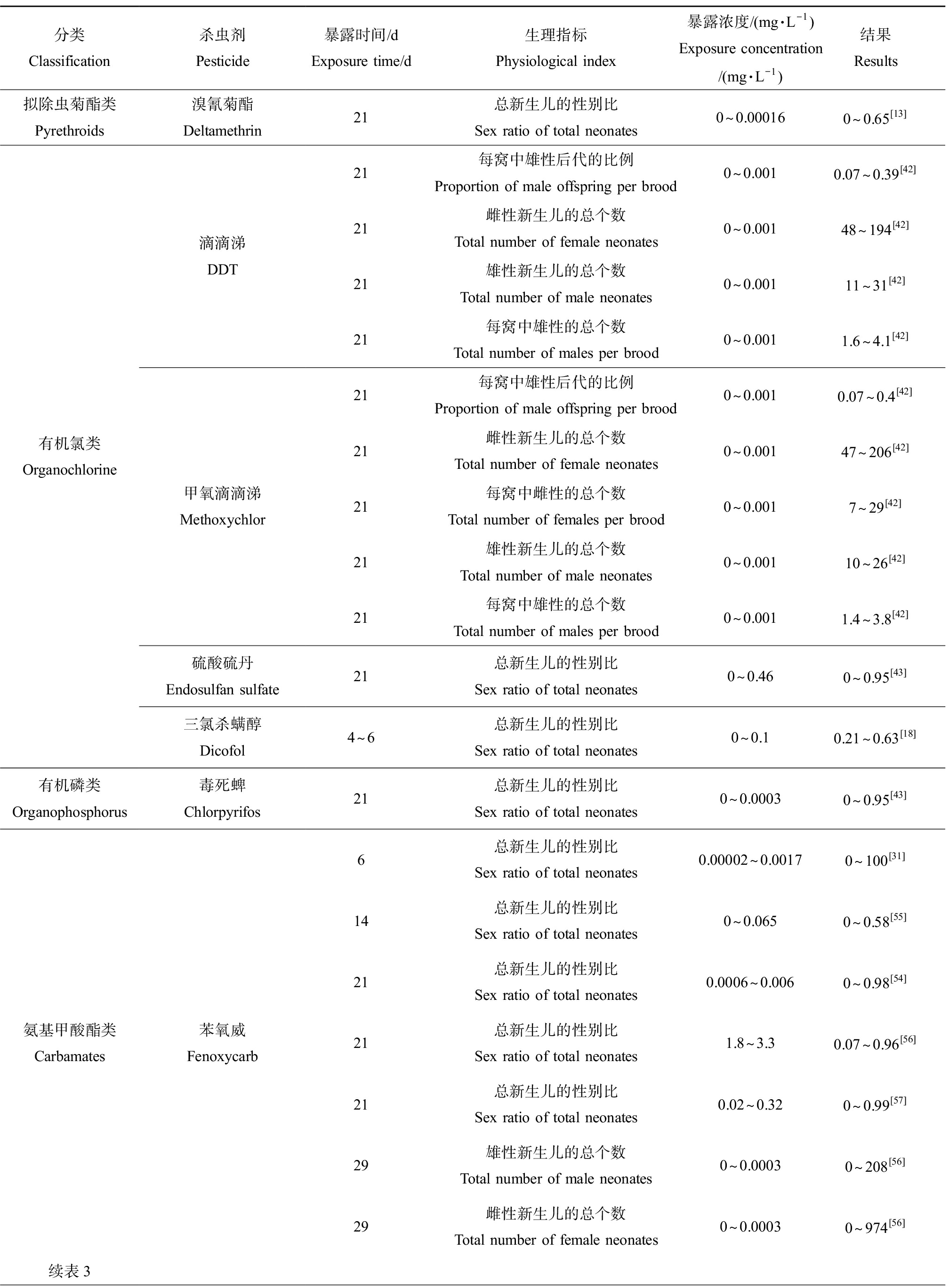

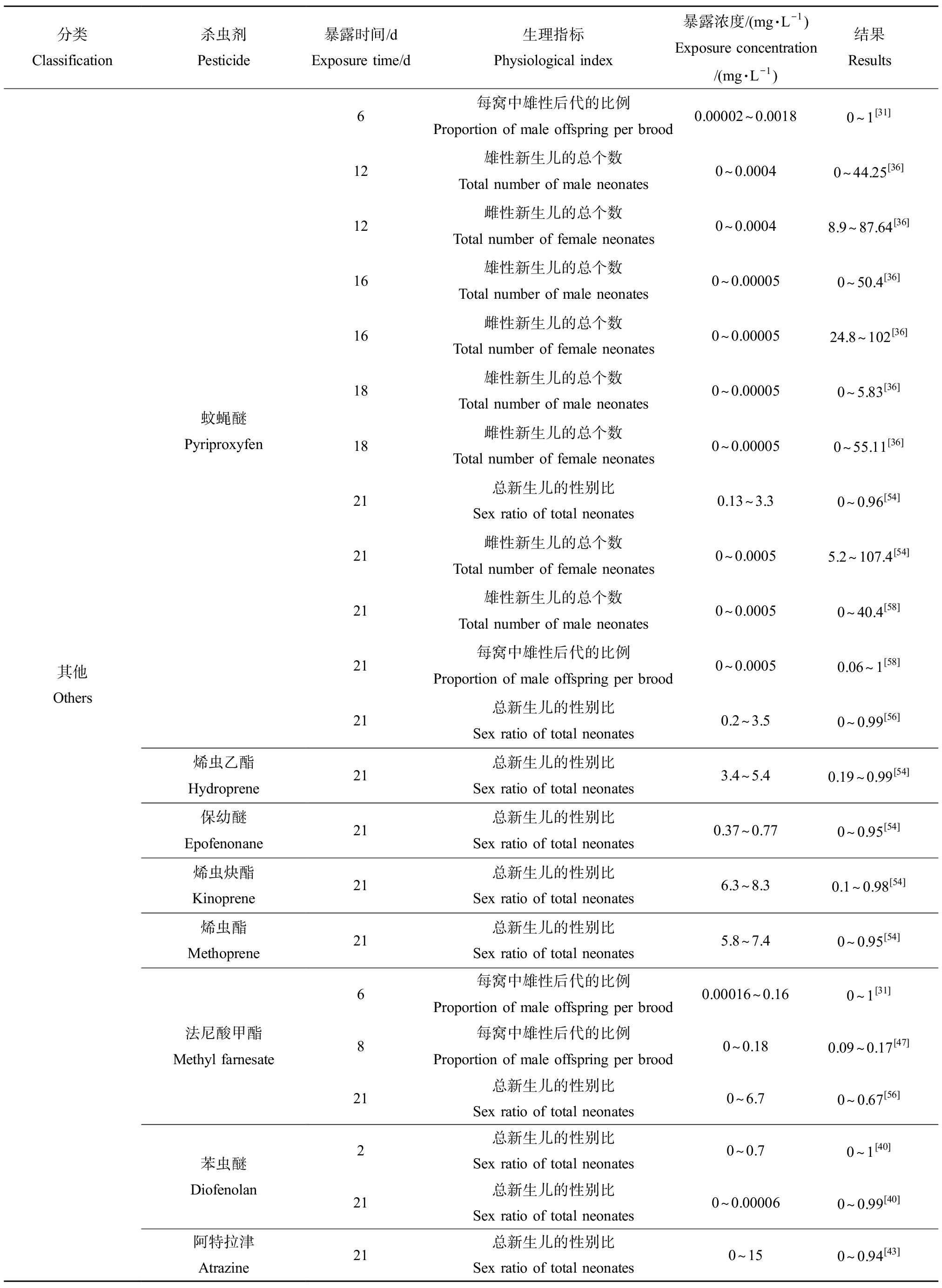

2.3 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞性别分化的影响

目前的研究证据表明,性别决定系统可以从现象上分为2组:基因型性别决定和环境性别决定[49-50]。在适宜的环境条件下,大型溞属于孤雌生殖。但是,一旦环境条件发生变化,大型溞就会改变繁殖策略开始产生雄性后代。大型溞的性别分化主要是通过第二触角的形态来判断,利用显微镜观察发现雄性大型溞的第二触角较长,而雌性大型溞的第二触角短而粗[12],由此能够清晰地区分大型溞的性别。

水溞的性别鉴定发生在卵沉积前1 h左右的关键时期[51],在大型溞雄性后代的诱导已被证明是检测保幼激素类似物的高度特异性终点[52]。目前已经有文献报道保幼激素会调节昆虫的各种生理过程,包括性腺发育、繁殖和变形等,具有诱导雄性后代产生的保幼激素。目前,具有内分泌干扰效应的杀虫剂对水溞性别分化的显著诱导作用已经得到了广泛的验证,如表3所示,这是由于大部分杀虫剂都属于保幼激素类似物且具有保幼激素活性导致的,但其具体的作用机理尚不清晰。例如,Abe等[40]通过研究发现苯虫醚作为一种保幼激素类似物能够显著诱导大型溞的性别分化,其诱导雄性后代的最低有效浓度为4 ng·L-1,且当暴露浓度为32 ng·L-1时能产生100%的雄性新生儿,表明雄性新生儿的比例与苯虫醚的暴露浓度呈正相关趋势。此外,在法尼酸甲酯、苯氧威和吡丙醚作用下均能诱导大型溞产生100%的雄性后代[53],通过评价溞类在水环境中的繁殖策略将有助于监测人类活动对水生生态环境的潜在不良影响。影响大型溞繁殖的浓度差异可能归因于化学物质所具有的毒性和保幼激素的活性。此外,大型溞对保幼激素类似物的敏感性具有遗传差异[54],因此由繁殖率下降和性别比改变引起的种群生长率的差异会可能会导致大型溞种群基因结构的改变从而对种群产生有害影响。

表2 常见的杀虫剂类内分泌干扰物对大型溞的生殖毒性

Table 2 Toxicity of common pesticides endocrine disrupting chemicals to the reproduction of Daphnia magna

分类Classification杀虫剂Pesticides暴露时间/dExposure time/d生理指标Physiological index暴露浓度/(mg·L-1)Exposure concentration/(mg·L-1)结果Results拟除虫菊酯类Pyrethroids溴氰菊酯Deltamethrin氯氰菊酯Cypermethrin21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.0001626.4~114.9[13]21总新生儿个数Total number of neonates0~0.00027~14[25]21繁殖窝数Brood number per female0~0.00023.7~6[25]有机氯类Organochlorine滴滴涕DDT21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.00179~220[42]甲氧滴滴涕Methoxychlor21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.00174~218[42]硫酸硫丹Endosulfan sulfate21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.464.8~113[43]有机磷类Organophosphorus毒死蜱Chlorpyrifos21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.000314.62~110.95[43]氨基甲酸酯类Carbamates苯氧威Fenoxycarb西维因Carbaryl21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.11.4~61.9[44]21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.00216.52~173.14[39]21胚胎孵化率Percentage of hatched individuals0~50.19~1[45]其他Others阿特拉津Atrazine蚊蝇醚Pyriproxyfen法尼酸甲酯Methyl farnesate苯虫醚Diofenolan烯虫乙酯Hydroprene烯虫炔酯Kinoprene保幼醚Epofenonane21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.1586.52~143.36[46]21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~1515.49~110.55[43]12总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.000438~87[36]18总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.0000520.8~83.5[36]16总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.0000575~102[36]8总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.182.96~9.05[47]21总新生儿的个数Total number of neonates0~0.0000618.42~163.84[40]21相对繁殖量Relative reproduction0~50.08~1[36]21相对繁殖量Relative reproduction0~80.03~1[36]21总新生儿个数Total number of neonates0~0.163~263[48]

表3 常见的杀虫剂类内分泌干扰物对大型溞性别分化的影响

Table 3 Effect of common pesticides endocrine disrupting chemicals on sex differentiation of Daphnia magna

分类Classification杀虫剂Pesticide暴露时间/dExposure time/d生理指标Physiological index暴露浓度/(mg·L-1)Exposure concentration /(mg·L-1)结果Results拟除虫菊酯类Pyrethroids溴氰菊酯Deltamethrin21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.000160~0.65[13]有机氯类Organochlorine滴滴涕DDT甲氧滴滴涕Methoxychlor硫酸硫丹Endosulfan sulfate三氯杀螨醇Dicofol21每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0~0.0010.07~0.39[42]21雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.00148~194[42]21雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.00111~31[42]21每窝中雄性的总个数Total number of males per brood0~0.0011.6~4.1[42]21每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0~0.0010.07~0.4[42]21雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.00147~206[42]21每窝中雌性的总个数Total number of females per brood0~0.0017~29[42]21雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.00110~26[42]21每窝中雄性的总个数Total number of males per brood0~0.0011.4~3.8[42]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.460~0.95[43]4~6总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.10.21~0.63[18]有机磷类Organophosphorus毒死蜱Chlorpyrifos21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.00030~0.95[43]氨基甲酸酯类Carbamates苯氧威Fenoxycarb6总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.00002~0.00170~100[31]14总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.0650~0.58[55]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.0006~0.0060~0.98[54]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates1.8~3.30.07~0.96[56]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.02~0.320~0.99[57]29雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.00030~208[56]29雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.00030~974[56]续表3

分类Classification杀虫剂Pesticide暴露时间/dExposure time/d生理指标Physiological index暴露浓度/(mg·L-1)Exposure concentration /(mg·L-1)结果Results其他Others蚊蝇醚Pyriproxyfen烯虫乙酯Hydroprene保幼醚Epofenonane烯虫炔酯Kinoprene烯虫酯Methoprene法尼酸甲酯Methyl farnesate苯虫醚Diofenolan阿特拉津Atrazine6每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0.00002~0.00180~1[31]12雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.00040~44.25[36]12雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.00048.9~87.64[36]16雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.000050~50.4[36]16雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.0000524.8~102[36]18雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.000050~5.83[36]18雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.000050~55.11[36]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.13~3.30~0.96[54]21雌性新生儿的总个数Total number of female neonates0~0.00055.2~107.4[54]21雄性新生儿的总个数Total number of male neonates0~0.00050~40.4[58]21每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0~0.00050.06~1[58]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.2~3.50~0.99[56]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates3.4~5.40.19~0.99[54]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0.37~0.770~0.95[54]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates6.3~8.30.1~0.98[54]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates5.8~7.40~0.95[54]6每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0.00016~0.160~1[31]8每窝中雄性后代的比例Proportion of male offspring per brood0~0.180.09~0.17[47]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~6.70~0.67[56]2总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.70~1[40]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~0.000060~0.99[40]21总新生儿的性别比Sex ratio of total neonates0~150~0.94[43]

2.4 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞蜕皮的影响

蜕皮是指生物体在生长过程中脱去旧表皮并长出新表皮的过程,受蜕皮激素控制,蜕皮激素是由P450酶对胆固醇进行酶化修饰而产生的类固醇激素,是一种普遍的生理现象[59]。大型溞为了适应体型增长需要更大的外骨骼。因此,蜕皮是大型溞发育成熟所必需的生理过程之一。未暴露的母本动物平均在6 d后进行第4次蜕皮,这标志着幼年生命阶段的结束。发育时间以及21 d后的繁殖量都与成功完成蜕皮周期有关,但在一定浓度的杀虫剂作用下大型溞会出现明显的蜕皮困难,因此蜕皮周期可以作为评价相关毒性的指标。

目前的研究已经表明部分与类固醇相似的杀虫剂会导致大型溞出现蜕皮延迟、蜕皮数量减少和不完全蜕皮等现象。例如,有研究表明,将大型溞短期暴露于20-羟基蜕皮激素后,与对照组比较发现大型溞的蜕皮频率会显著降低,可能与蜕皮液中分解酶壳二糖酶的活性有关[60]。由于一些类固醇与蜕皮激素具有相似的结构,因此硫丹与蜕皮激素受体的结合阻止了蜕皮激素与蜕皮激素受体的特异性结合,从而导致大型溞蜕皮的延迟[61]。因此,蜕皮这一生理指标可以看作是反映类固醇类杀虫剂对甲壳动物毒性效应的典型标志物之一。

3 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞的毒性作用机制(The toxic mechanism of pesticides EDCs on Daphnia magna)

3.1 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞生物酶活性的影响

3.1.1 杀虫剂对氧化应激相关酶的影响

随着分子生物学技术的发展,已有大量研究根据基因表达水平研究污染物对大型溞的生长、繁殖等方面的影响,以识别改变的生物途径和潜在的生物标记物。当大型溞暴露于外源化合物时,可能会在亚致死和生态相关的水平发生氧化应激,而氧化应激会导致脂质过氧化、膜功能障碍、DNA和蛋白质损伤等[62]。已有大量研究表明,杀虫剂会改变水生动物体内抗氧化酶的活性,诱导氧化应激的产生。例如,当大型溞暴露于增塑剂双酚F时,大型溞会通过激活抗氧化系统中的超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)、过氧化氢酶(CAT)和谷胱甘肽转移酶(GST)来平衡细胞体内的活性氧;但是,过量活性氧的产生会导致显著的氧化损伤包括抗氧化酶失活、DNA损伤和脂质过氧化等现象。其中脂质过氧化是导致细胞功能受损的主要机制,具体表现为脂质过氧化的产物丙二醛(MDA)含量的增加,如当大型溞暴露于0.1 μg·L-1的双酚A时,MDA的含量相较于对照组增加了10%[63]。因此,脂质过氧化和抗氧化防御系统能作为生物标志物来评价环境中双酚类物质的毒性作用。

3.1.2 杀虫剂类EDCs对神经系统相关酶的影响

大部分杀虫剂对大型溞具有神经毒性作用,具体表现为乙酰胆碱酯酶(AChE)活性的抑制延长了神经传递,甚至在高剂量暴露下出现致死现象,对大型溞的健康和生存产生了严重的不良影响[64-65]。大量研究表明AChE活性已经被用于检测有机磷杀虫剂和氨基酸甲酯类杀虫剂对无脊椎动物如大型溞的影响[37-38,66]。乙酰胆碱(ACh)是神经系统的重要神经递质之一,存在于神经肌肉连接处、内脏运动系统的突触和中枢神经系统等位置,对维持水生生物的肌肉功能具有重要作用,其含量的改变会显著影响肌肉收缩进而改变行为活动[67-68]。AChE作为水解酶,存在于神经和肌肉细胞之间的突触间隙,能使ACh快速水解有效地中止突触传递[69]。当大型溞暴露于杀虫剂胺甲萘时,AChE活性会忽然显著下降,但由于补偿机制即AChE合成的刺激,其活性会在20 h内恢复到60%左右,由于这种恢复是有限的,AChE活性会随着暴露时间再次显著下降,从而导致ACh在突触间隙内的浓度升高诱导信号转导紊乱[69-70]。AChE活性的抑制会导致神经末梢激活紊乱、神经传导能力丧失和生物体瘫痪等现象,进而表现为多动、协调性丧失、抽搐和瘫痪等多种行为变化最终死亡[71]。Ren等[72]的研究验证了上述结果,当大型溞暴露于高浓度敌敌畏时,AChE活性在6 h内显著降低并表现出游泳能力丧失直至沉入容器底部。由上述研究可知,神经系统损伤会使大型溞丧失运动和摄食能力,从而造成致命影响,这可能是大型溞死亡率上升的主要原因。此外,随着杀虫剂种类的日益丰富,研究人员发现新烟碱类、有机氯类、苯基吡唑类和除虫菊酯等杀虫剂也能显著抑制AChE活性,并对神经系统轴突、突触前和突触后的靶点具有不良影响[73]。因此,AChE活性可以作为大型溞响应杀虫剂毒性作用的生物标志物,为揭示新兴杀虫剂对大型溞等水生动物的毒性作用机制提供了参考依据。

3.2 杀虫剂类EDCs对大型溞生物基因表达的影响

随着分子生态毒理学领域中组学工具的广泛应用,通过常见的DNA微阵列技术、转录组测序技术和定量实时PCR验证等组学技术手段来揭示污染物及其代谢产物与核酸和酶等生物大分子之间的相互作用关系,以识别改变的生物途径和潜在的生物标记物[74],为表征外源物质的毒性作用模式和识别作用途径提供基础。有研究将大型溞暴露于甲维盐48 h后测定了整体转录组的变化和蜕皮受体的结合能力,发现改变了神经内分泌调节的蜕皮、扰乱了能量稳态、抑制DNA修复和诱导程序性细胞死亡途径与大型溞的蜕皮频率和存活率下降有关[75]。

通过基因表达水平的变化,以验证生理指标与特定基因功能之间的关系,并揭示其作用机理,为生态风险评估提供依据。通过总结目前的研究进展发现,基于抗氧化防御中酶活性、基因组学和转录组学来揭示生物体表型变化与分子作用机制之间关系的研究较为广泛。

通过整理文献发现,已有大量的研究表明具有保幼激素活性的杀虫剂能在分子水平上显著地影响大型溞,并通过相关的生物标志物将转录组和有害表型反应联系起来。例如,Kim等[44]利用寡核苷酸DNA微阵列技术发现,苯氧威的暴露浓度与卵黄蛋白原基因的表达水平呈负相关关系,当苯氧威的暴露浓度为0.01 μg·L-1时,卵黄蛋白原基因的表达水平比对照组低约75%。同时,Toyota等[16]也证明了大型溞暴露于保幼激素类似物后,新生儿数量的减少归因于卵黄蛋白原基因表达的抑制,但具体的作用机理仍不清楚。由此可见,为胚胎发育提供能量的卵黄蛋白原基因可用作评估杀虫剂对大型溞繁殖毒性的重要生物标志物。保幼激素酯酶和保幼激素环氧化物水解酶是2种保幼激素降解酶,主要用于维持昆虫体内正常的保幼激素滴度[76]。有研究表明当大型溞暴露于烯虫酯、保幼醚和中、高浓度的苯氧威时,保幼激素环氧化物水解酶的表达上调,而保幼激素酯酶的表达没有变化[77]。然而,当大型溞暴露于苯虫醚时保幼激素酯酶的表达会显著上调。因此可知,保幼激素降解酶对具有保幼激素活性的化学物质具有不同的选择性[40],能够用作杀虫剂暴露下潜在的生物标志物。

将水溞的整个基因组表达水平的改变用于分析杀虫剂的作用机理,了解孤雌生殖的遗传基础及其对基因方面的影响。然而,关于大型溞的雄性诱导机制和性别分化的相关研究仍然较少。法尼酸甲酯是一种内源性的保幼激素,它在雄性新生儿中的含量显著高于雌性新生儿。此外,已经有研究证明法尼酸甲酯信号的传导可以通过不利环境刺激来确定大型溞新生儿的性别[78-79]。淡水枝角大型溞在短日照条件下会产生雄性大型溞,这是由于NMDA型离子型谷氨酸受体信号的激活促进了法尼酸甲酯的合成。当大型溞暴露于外源性法尼酸甲酯时,蛋白激酶C可能与法尼酸甲酯信号的传导有关[80]。此外,保幼激素含量在诱导大型溞性别决定中也发挥着重要作用。Masteling等[62]研究发现当大型溞暴露于硫丹硫酸盐、烯虫乙酯时会以浓度依赖的方式产生雄性后代。其中,当大型溞暴露于保幼激素Ⅲ并产生雄性新生儿时,基因Dsx1和Dsx2的表达均上调,这一过程有助于黄体形成过程中的性别决定,且当雄性新生儿发育至性成熟时,基因Dsx2的表达会显著增加[81]。由此可知,具有保幼激素活性的杀虫剂是通过干扰内分泌系统来影响大型溞的生殖发育。但就目前的研究现状而言,仍有许多与性别分化与生殖相关的基因是未知的,需要通过基因组学和转录组学研究来进一步了解。

4 展望(Prospect)

近些年,关于杀虫剂对大型溞的毒理学研究已经取得了显著的进展,但目前的大多数研究仅局限于杀虫剂对水生蚤类的表型影响,关于其生态毒性效应研究仍缺乏系统性,因此,今后可在以下2个方面做进一步的研究。

首先,已开展的研究大多是针对一种污染物对水生生物的毒性效应,关于2种及2种以上不同污染物复合毒性的研究相对较少。在自然环境中,通常是多种化学物质共同存在,考虑到所研究问题的现实性,应该更加关注杀虫剂的复合毒性。例如,有研究通过构建模型等方法研究氟苯达唑与芬苯达唑对大型溞的混合毒性,能够更准确系统地评价污染物质对生态环境所造成的危害[82]。

其次,杀虫剂大多是难降解的污染物质,会在自然环境中长期存在并且不断累积,因此会对生物体产生慢性毒性。但是,部分污染物质毒性较弱,需要经过多个世代的暴露后才会对后代产生毒性作用,因此有必要对污染物进行多代研究来更准确地揭示其作用机制,应用长期和多代暴露方法来评估杀虫剂对生态环境的风险具有重要意义。

通讯作者简介:李琦(1974—),女,博士,教授,主要研究方向为环境有机污染物和重金属的污染控制及修复、水资源和水环境安全。

[1] 方琪, 马彦博, 张思远, 等. 农药内分泌干扰效应研究进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2017, 12(1): 98-110

Fang Q, Ma Y B, Zhang S Y, et al. Research progress in endocrine disrupting effects of pesticides [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2017, 12(1): 98-110 (in Chinese)

[2] Gore A C, Chappell V A, Fenton S E, et al. EDC-2: The endocrine society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals [J]. Endocrine Reviews, 2015, 36(6): E1-E150

[3] 杨会会. 湖北省地表水中有机磷农药的分布和健康风险评价[D]. 武汉: 华中师范大学, 2014, 12(2): 13-36

[4] 吕潇, 李慧冬, 杜红霞, 等. 农药类内分泌干扰物的研究进展[J]. 华中农业大学学报, 2006, 25(1): 94-100

Lv X, Li H D, Du H X, et al. Advances in endocrine disrupting pesticides [J]. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University: Natural Science Edition, 2006, 25(1): 94-100 (in Chinese)

[5] Juberg D R, Borghoff S J, Becker R A, et al. Lessons learned, challenges, and opportunities: The US endocrine disruptor screening program [J]. ALTEX, 2014, 31(1): 63-78

[6] Jordão R, Casas J, Fabrias G, et al. Obesogens beyond vertebrates: Lipid perturbation by tributyltin in the crustacean Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2015, 123(8): 813-819

[7] Jeong T Y, Simpson M J. Reproduction stage specific dysregulation of Daphnia magna metabolites as an early indicator of reproductive endocrine disruption [J]. Water Research, 2020, 184: 116107

[8] Han S, Choi K, Kim J, et al. Endocrine disruption and consequences of chronic exposure to ibuprofen in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) and freshwater cladocerans Daphnia magna and Moina macrocopa [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2010, 98(3): 256-264

[9] Printes L B, Fellowes M D E, Callaghan A. Clonal variation in acetylcholinesterase biomarkers and life history traits following OP exposure in Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2008, 71(2): 519-526

[10] Ivorra L, Cardoso P G, Chan S K, et al. Environmental characterization of 4,4’-dichlorobenzophenone in surface waters from Macao and Hong Kong coastal areas (Pearl River Delta) and its toxicity on two biological models: Artemia salina and Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 171: 1-11

[11] Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 202: Daphnia sp. Acute immobilisation test [R]. Paris: OECD, 2004

[12] Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 211: Daphnia magna reproduction test [R]. Paris: OECD, 2012

[13] Toumi H, Boumaiza M, Millet M, et al. Effects of deltamethrin (pyrethroid insecticide) on growth, reproduction, embryonic development and sex differentiation in two strains of Daphnia magna (Crustacea, Cladocera) [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2013, 458-460: 47-53

[14] Kim Y, Jung J, Oh S, et al. Aquatic toxicity of cartap and cypermethrin to different life stages of Daphnia magna and Oryzias latipes [J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 2008, 43(1): 56-64

[15] Mokry L E, Hoagland K D. Acute toxicities of five synthetic pyrethroid insecticides to Daphnia magna and Ceriodaphnia dubia [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 1990, 9(8): 1045

[16] Toyota K, Williams T D, Sato T, et al. Comparative ovarian microarray analysis of juvenile hormone-responsive genes in water flea Daphnia magna: Potential targets for toxicity [J]. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 2017, 37(3): 374-381

[17] Villarroel M J, Sancho E, Ferrando M D, et al. Effect of an acaricide on the reproduction and survival of Daphnia magna [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1999, 63(2): 167-173

[18] Haeba M H, Hilscherová K, Mazurová E, et al. Selected endocrine disrupting compounds (vinclozolin, flutamide, ketoconazole and dicofol): Effects on survival, occurrence of males, growth, molting and reproduction of Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2008, 15(3): 222-227

[19] Hernando M D, Ejerhoon M, Fernández-Alba A R, et al. Combined toxicity effects of MTBE and pesticides measured with Vibrio fischeri and Daphnia magna bioassays [J]. Water Research, 2003, 37(17): 4091-4098

[20] Palma P, Palma V L, Fernandes R M, et al. Acute toxicity of atrazine, endosulfan sulphate and chlorpyrifos to Vibrio fischeri, Thamnocephalus platyurus and Daphnia magna, relative to their concentrations in surface waters from the Alentejo Region of Portugal [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2008, 81(5): 485-489

[21] Ren Z M, Li Z L, Zha J M, et al. The avoidance responses of Daphnia magna to the exposure of organophosphorus pesticides in an on-line biomonitoring system [J]. Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 2009, 14(3): 405-410

[22] Hartgers E M, Heugens E H, Deneer J W. Effect of lindane on the clearance rate of Daphnia magna [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1999, 36(4): 399-404

[23] Bettinetti R, Croce V, Noè F, et al. Ecotoxicity of p,p’-DDE to Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2013, 22(8): 1255-1263

[24] Manar R, Bessi H, Vasseur P. Reproductive effects and bioaccumulation of chlordane in Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2009, 28(10): 2150-2159

[25] Qiu X C, Tanoue W, Kawaguchi A, et al. Interaction patterns and toxicities of binary and ternary pesticide mixtures to Daphnia magna estimated by an accelerated failure time model [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 607-608: 367-374

[26] Trac L N, Andersen O, Palmqvist A. Deciphering mechanisms of malathion toxicity under pulse exposure of the freshwater cladoceran Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2016, 35(2): 394-404

[27] Andersen T H, Tjørnhøj R, Wollenberger L, et al. Acute and chronic effects of pulse exposure of Daphnia magna to dimethoate and pirimicarb [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2006, 25(5): 1187-1195

[28] Liess M, von der Ohe P C. Analyzing effects of pesticides on invertebrate communities in streams [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2005, 24(4): 954-965

[29] Demetrio P M, Bonetto C, Ronco A E. The effect of cypermethrin, chlorpyrifos, and glyphosate active ingredients and formulations on Daphnia magna (Straus) [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2014, 93(3): 268-273

[30] George T K, Liber K. Laboratory investigation of the toxicity and interaction of pesticide mixtures in Daphnia magna [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2007, 52(1): 64-72

[31] Matsumoto T, Ikuno E, Itoi S, et al. Chemical sensitivity of the male daphnid, Daphnia magna, induced by exposure to juvenile hormone and its analogs [J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 72(3): 451-456

[32] Coors A, Vanoverbeke J, de Bie T, et al. Land use, genetic diversity and toxicant tolerance in natural populations of Daphnia magna [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2009, 95(1): 71-79

[33] Wilsont P C, Foos J F. Survey of carbamate and organophosphorous pesticide export from a South Florida (U.S.A.) agricultural watershed: Implications of sampling frequency on ecological risk estimation [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2006, 25(11): 2847-2852

[34] Pfaff J, Reinwald H, Ayobahan S U, et al. Toxicogenomic differentiation of functional responses to fipronil and imidacloprid in Daphnia magna [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2021, 238: 105927

[35] Gauthier J R, Mabury S A. The sulfoximine insecticide sulfoxaflor and its photodegradate demonstrate acute toxicity to the nontarget invertebrate species Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2021, 40(8): 2156-2164

[36] Ginjupalli G K, Baldwin W S. The time- and age-dependent effects of the juvenile hormone analog pesticide, pyriproxyfen on Daphnia magna reproduction [J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 92(9): 1260-1266

[37] Barata C, Solayan A, Porte C. Role of B-esterases in assessing toxicity of organophosphorus (chlorpyrifos, malathion) and carbamate (carbofuran) pesticides to Daphnia magna [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2004, 66(2): 125-139

[38] Xuereb B, Noury P, Felten V, et al. Cholinesterase activity in Gammarus pulex (Crustacea Amphipoda): Characterization and effects of chlorpyrifos [J]. Toxicology, 2007, 236(3): 178-189

[39] Oda S, Tatarazako N, Watanabe H, et al. Genetic differences in the production of male neonates in Daphnia magna exposed to juvenile hormone analogs [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 63(9): 1477-1484

[40] Abe R, Toyota K, Miyakawa H, et al. Diofenolan induces male offspring production through binding to the juvenile hormone receptor in Daphnia magna [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2015, 159: 44-51

[41] Goto T, Hiromi J. Toxicity of 17alpha-ethynylestradiol and norethindrone, constituents of an oral contraceptive pill to the swimming and reproduction of cladoceran Daphnia magna, with special reference to their synergetic effect [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2003, 47(1-6): 139-142

[42] Baer K N, Owens K D. Evaluation of selected endocrine disrupting compounds on sex determination in Daphnia magna using reduced photoperiod and different feeding rates [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1999, 62(2): 214-221

[43] Palma P, Palma V L, Matos C, et al. Assessment of the pesticides atrazine, endosulfan sulphate and chlorpyrifos for juvenoid-related endocrine activity using Daphnia magna [J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 76(3): 335-340

[44] Kim J, Kim Y, Lee S, et al. Determination of mRNA expression of DMRT93B, vitellogenin, and cuticle 12 in Daphnia magna and their biomarker potential for endocrine disruption [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2011, 20(8): 1741-1748

[45] Navis S, Waterkeyn A, Voet T, et al. Pesticide exposure impacts not only hatching of dormant eggs, but also hatchling survival and performance in the water flea Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2013, 22(5): 803-814

[46] Religia P, Kato Y, Fukushima E O, et al. Atrazine exposed phytoplankton causes the production of non-viable offspring on Daphnia magna [J]. Marine Environmental Research, 2019, 145: 177-183

[47] Lampert W, Lampert K P, Larsson P. Induction of male production in clones of Daphnia pulex by the juvenoid hormone methyl farnesoate under short photoperiod [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2012, 156(2): 130-133

[48] Oda S, Tatarazako N, Watanabe H, et al. Production of male neonates in Daphnia magna (Cladocera, Crustacea) exposed to juvenile hormones and their analogs [J]. Chemosphere, 2005, 61(8): 1168-1174

[49] Kopp A. Dmrt genes in the development and evolution of sexual dimorphism [J]. Trends in Genetics, 2012, 28(4): 175-184

[50] Marín I, Baker B S. The evolutionary dynamics of sex determination [J]. Science, 1998, 281(5385): 1990-1994

[51] Palma P, Palma V L, Fernandes R M, et al. Endosulfan sulphate interferes with reproduction, embryonic development and sex differentiation in Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2009, 72(2): 344-350

[52] Olmstead A W, LeBlanc G A. Insecticidal juvenile hormone analogs stimulate the production of male offspring in the crustacean Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2003, 111(7): 919-924

[53] de Souza Machado A A, Zarfl C, Rehse S, et al. Low-dose effects: Nonmonotonic responses for the toxicity of a Bacillus thuringiensis biocide to Daphnia magna [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(3): 1679-1686

[54] Tatarazako N, Oda S. The water flea Daphnia magna (Crustacea, Cladocera) as a test species for screening and evaluation of chemicals with endocrine disrupting effects on crustaceans [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2007, 16(1): 197-203

[55] Navis S, Waterkeyn A, de Meester L, et al. Acute and chronic effects of exposure to the juvenile hormone analog fenoxycarb during sexual reproduction in Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2018, 27(5): 627-634

[56] Tatarazako N, Oda S, Watanabe H, et al. Juvenile hormone agonists affect the occurrence of male Daphnia [J]. Chemosphere, 2003, 53(8): 827-833

[57] Davies R, Zou E M. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers disrupt molting in neonatal Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology, 2012, 21(5): 1371-1380

[58] Watanabe H, Oda S, Abe R, et al. Comparison of the effects of constant and pulsed exposure with equivalent time-weighted average concentrations of the juvenile hormone analog pyriproxyfen on the reproduction of Daphnia magna [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 195: 810-816

[59] Hassold E, Backhaus T. Chronic toxicity of five structurally diverse demethylase-inhibiting fungicides to the crustacean Daphnia magna: A comparative assessment [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2009, 28(6): 1218-1226

[60] Song Y, Evenseth L M, Iguchi T, et al. Release of chitobiase as an indicator of potential molting disruption in juvenile Daphnia magna exposed to the ecdysone receptor agonist 20-hydroxyecdysone [J]. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 2017, 80(16-18): 954-962

[61] Zou E M, Fingerman M. Effects of estrogenic xenobiotics on molting of the water flea, Daphnia magna [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 1997, 38(3): 281-285

[62] Masteling R P, Castro B B, Antunes S C, et al. Whole-organism and biomarker endpoints in Daphnia magna show uncoupling of oxidative stress and endocrine disruption in phenolic derivatives [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 134: 64-71

[63] Liu T, He Z R. Vessel segmentation using principal component based threshold algorithm [C]. Nanchang: 2019 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), 2019: 2739-2741

[64] Hassold E, Backhaus T. Chronic toxicity of five structurally diverse demethylase-inhibiting fungicides to the crustacean Daphnia magna: A comparative assessment [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2009, 28(6): 1218-1226

[65] Scott G R, Sloman K A. The effects of environmental pollutants on complex fish behaviour: Integrating behavioural and physiological indicators of toxicity [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2004, 68(4): 369-392

[66] Toumi H, Boumaiza M, Millet M, et al. Is acetylcholinesterase a biomarker of susceptibility in Daphnia magna (Crustacea, Cladocera) after deltamethrin exposure? [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 120: 351-356

[67] Kotikova E A, Raikova O I, Flyatchinskaya L P, et al. Rotifer muscles as revealed by phalloidin-TRITC staining and confocal scanning laser microscopy [J]. Acta Zoologica, 2001, 82(1): 1-9

[68] Fukuto T R. Mechanism of action of organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1990, 87: 245-254

[69] Ubaid ur Rahman H, Asghar W, Nazir W, et al. A comprehensive review on chlorpyrifos toxicity with special reference to endocrine disruption: Evidence of mechanisms, exposures and mitigation strategies [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 755: 142649

[70] Venkatalaxmi A, Padmavathi B S, Amaranath T. A general solution of unsteady Stokes equations [J]. Fluid Dynamics Research, 2004, 35(3): 229-236

[71] Casida J E. Esterase inhibitors as pesticides: Because of favorable biological properties they are displacing other types of established compounds [J]. Science, 1964, 146(3647): 1011-1017

[72] Ren Z M, Zhang X, Wang X G, et al. AChE inhibition: One dominant factor for swimming behavior changes of Daphnia magna under DDVP exposure [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 120: 252-257

[73] Crivellente F, Hart A. Establishment of cumulative assessment groups of pesticides for their effects on the nervous system [J]. EFSA Journal, 2019, 17(9): e05800

[74] 巩宁, 孟紫强, 邵魁双, 等. 水蚤分子生态毒理学研究进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2020, 15(2): 11-18

Gong N, Meng Z Q, Shao K S, et al. Advances in ecotoxicogenomics with water fleas [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2020, 15(2): 11-18 (in Chinese)

[75] Masteling R P, Castro B B, Antunes S C, et al. Whole-organism and biomarker endpoints in Daphnia magna show uncoupling of oxidative stress and endocrine disruption in phenolic derivatives [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 134: 64-71

[76] Baldwin W S, Graham S E, Shea D M, et al. Metabolic androgenization of female Daphnia magna by the xenoestrogen 4-nonylphenol [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 1997, 16(9): 1905

[77] Toyota K, Kato Y, Sato M, et al. Molecular cloning of doublesex genes of four Cladocera (water flea) species [J]. BMC Genomics, 2013, 14: 239

[78] Ignace D D, Dodson S I, Kashian D R. Identification of the critical timing of sex determination in Daphnia magna (Crustacea, Branchiopoda) for use in toxicological studies [J]. Hydrobiologia, 2011, 668(1): 117-123

[79] Kato Y, Kobayashi K, Watanabe H, et al. Environmental sex determination in the branchiopod crustacean Daphnia magna: Deep conservation of a doublesex gene in the sex-determining pathway [J]. PLoS Genetics, 2011, 7(3): e1001345

[80] Toyota K, Miyakawa H, Yamaguchi K, et al. NMDA receptor activation upstream of methyl farnesoate signaling for short day-induced male offspring production in the water flea, Daphnia pulex [J]. BMC Genomics, 2015, 16(1): 186

[81] Wuerz M, Whyard S, Loadman N L, et al. Sex determination and gene expression in Daphnia magna exposed to juvenile hormone [J]. Journal of Plankton Research, 2019, 41(4): 393-406

[82] Puckowski A, Stolte S, Wagil M, et al. Mixture toxicity of flubendazole and fenbendazole to Daphnia magna [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2017, 220(3): 575-582