重金属可以通过食物链传递带来生物毒性[1],引起了学界的高度重视,重金属污染已成为世界性的环境问题。儿童正处于生理发育的关键时期,与成人相比对重金属等环境污染物更为敏感[2]。重金属对人体多种器官均具有毒性作用[3-4],儿童即使暴露于极低浓度的Pb也会影响智力发育[5]。儿童接触重金属污染的物品曾导致严重的群体Pb中毒事件[6]。除Pb和Cd外的其他重金属,如Cr和Ni的污染受到较少关注,但其危害不容小觑。Cr被认定为致癌物质,长期摄入Cr可能在小肠中诱发肿瘤[7];而摄入过量的Ni会引发心血管和肾脏疾病等[8]。儿童的环境污染物摄入途径包括饮食、呼吸空气、土壤接触[9-10]及皮肤接触[11]。作为儿童密切接触的日用品,塑料玩具中含有多种添加剂类污染物如增塑剂[12]和重金属[13]。玩具生产过程中常使用重金属作为塑料的稳定剂,或使用含有重金属的涂料[14],例如过去Pb常添加于玩具的油漆中[13,15]。玩具中的重金属主要通过皮肤接触和口腔进入儿童体内[16]。

中国是世界上最大的玩具生产国和出口国,随着社会经济的发展,玩具消费增长趋势明显。目前世界各国已对儿童产品中重金属污染进行严格监管,但最近的研究仍然显示,具有重金属残留的玩具仍在市场上广泛流通[13,17-18]。再生塑料的使用是玩具中检出重金属的原因之一。塑料回收是国内废弃塑料的主要处理方法,废塑料经加工可再生产为包括塑料玩具在内的各类塑料产品。在废塑料的回收加工过程中,原有的重金属(例如Pb、Cr和Cd)、增塑剂(如邻苯二甲酸酯)、阻燃剂(多溴联苯醚)等塑料添加剂仍遗留在新产品中[19],并且与新添加的塑料添加剂(例如抗氧剂、增塑剂和着色剂等)混合[20]。上述的各类塑料添加剂尽管已被世界各国禁用,但仍能够通过废塑料的回收再生进入新产品,从而带来持续的环境健康风险。玩具中再生塑料的使用和重金属污染间的关系值得重视。已有的研究大多只检测塑料玩具中的重金属含量,未对塑料玩具的材质进行鉴别,极少关注再生塑料导致的环境污染物残留。本研究的目的如下:(1)了解玩具中各类重金属(Al、Ba、Cd、Co、Cr、Cu、Mn、Ni、Pb和Zn)的污染现状;(2)分析塑料玩具中重金属的组成,以及再生塑料与重金属污染的关系;(3)初步评估玩具对儿童造成的重金属暴露风险。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 实验材料

本研究购买的玩具包括以下类型:硬塑料类玩具(n=51)、软塑料类玩具(n=50)、泡沫塑料玩具(n=31)、毛绒玩具(n=50)和木制玩具(n=50)。

实验用浓硝酸和氢氟酸均为优级纯,购自广州化学试剂厂。

1.2 实验方法

玩具材料的鉴定。通过傅里叶变换红外光谱仪(VERTEX 70,德国BRUKER)对玩具中塑料聚合物进行聚合物材质的鉴定,光谱范围4 000~400 cm-1,分辨率<0.5 cm-1。

玩具总重金属含量测定。剪或刮取玩具表面,向约0.4 g样品中加入12 mL混合酸(浓硝酸/氢氟酸,3/1,V/V))在180 ℃下进行微波消解。消解完毕后赶酸至消解液近无,用双蒸水将样品溶液转移到10 mL离心管中,定容,摇匀。并用0.22 μm滤膜过滤,所得待测液在4 ℃下保存至分析。待测液使用电感耦合等离子体发射光谱仪(ICP-OES 5100VDV,Agilent)测定Ba、Ni、Cr、Pb、Cu、Mn、Al、Co、Cd和Zn含量。设置空白对照组和标准参考物质的常规分析,玩具的重金属含量扣除空白样品平均值。定量限设置为空白样品结果的3倍标准偏差值。重金属全量分析过程中以环境标准物质土壤GBW07430(中国地质科学院地球物理地球化学勘查研究所)为质量控制样品,质控样品的各项重金属元素含量回收率均在91%~107%范围内。

1.3 数据统计与分析

采用SSPS 22.0 Windows版软件(SPSS Inc.)对实验数据进行统计计算。未检出的值以一半的定量限替换。玩具中重金属浓度不服从正态分布,本研究通过Spearman相关系数分析确定样品中重金属含量之间的相关性。通过Kruskal-Wallis检验和Mann-Whitney U检验确定玩具中重金属含量差异是否显著。显著水平设置为P=0.05。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 塑料玩具的材质

2.1.1 玩具的聚合物类型

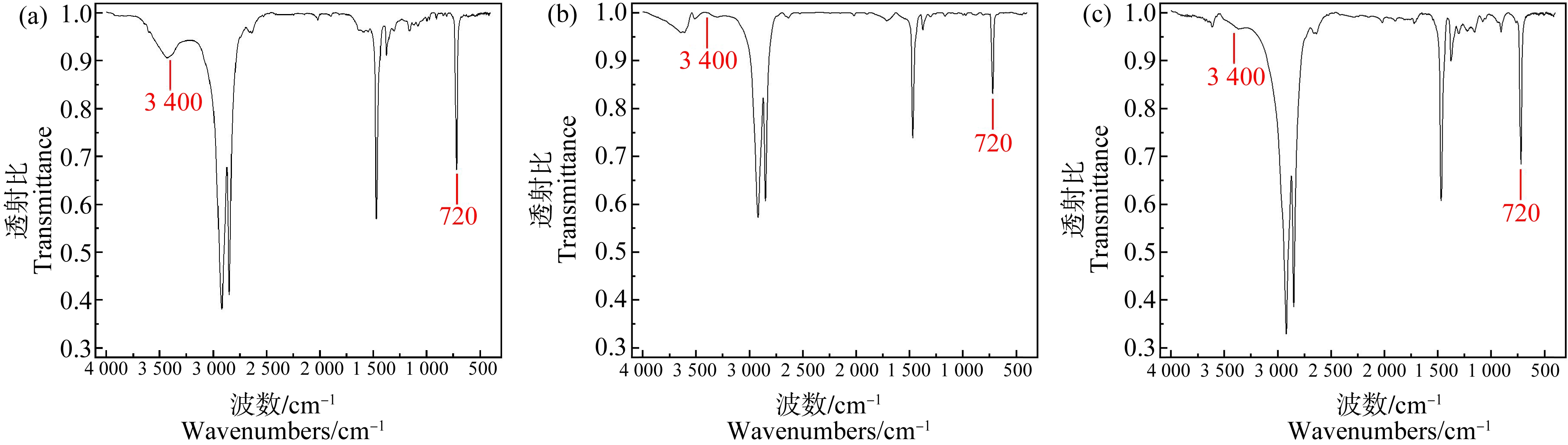

玩具样品中的塑料类型如图1所示,硬塑料类、软塑料类和泡沫塑料类玩具中分别有100%、60%和70%的样品能够通过红外光谱方法鉴定塑料材质。本研究共鉴定出9种聚合物,硬塑料类玩具的主要材质为丙烯腈-丁二烯-苯乙烯(ABS)和聚丙烯(PP),分别占所有硬塑料样品的39%和37%。ABS和PP塑料生产成本低,且硬度较好,是应用于硬塑料玩具的主要原因。聚乙烯(PE)是软塑料类玩具的主要材质,占比80%以上。泡沫塑料类玩具的主要材质是聚氨酯(PU),占比43%,其次为PE和PP,分别占比24%和19%。本研究的结果与文献报道相似,硬塑料和泡沫塑料玩具的主要材质分别是PP和PU[21]。Babich等[12]测得儿童塑料用品的主要材质是聚氯乙烯(PVC)、PP和PE,可能与样品中牙胶占比较多有关,因为PVC常用于生产牙胶类产品。

2.1.2 再生塑料的鉴定

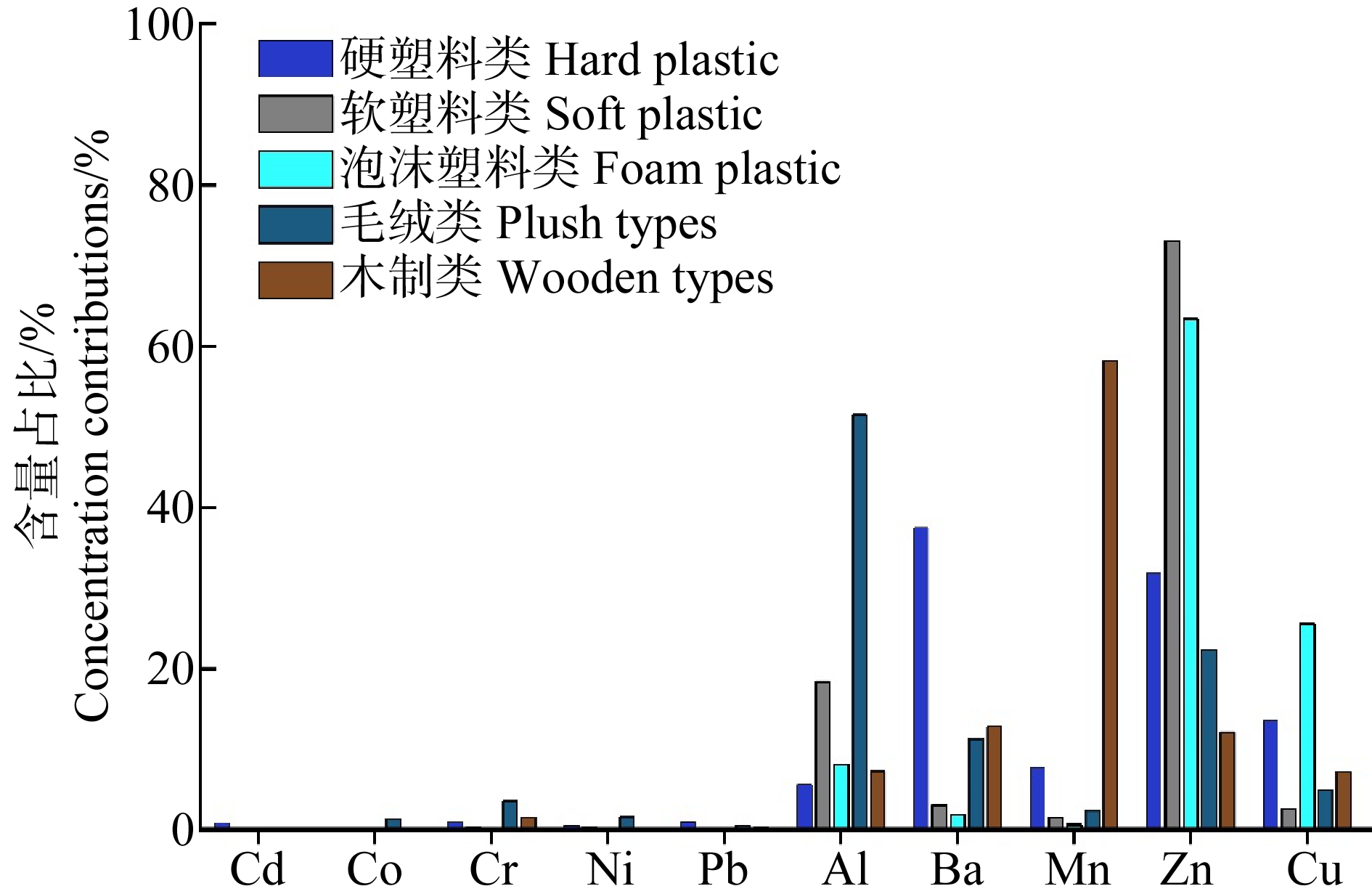

废塑料的回收利用中常经历高温高压等加工过程,存在高分子聚合物的降解氧化反应,导致C—O、O—H等基团的生成[22]。本研究根据PE、PP、PS和ABS玩具的红外光谱中是否存在明显的C—O和O—H基团来判断该样品是否为再生塑料材质。硬塑料类玩具中的再生塑料样品占51%,而软塑料和泡沫塑料中无明显的C—O和O—H基团。但红外光谱方法鉴定再生塑料也存在一定缺陷,C—O和O—H基团的特征峰可能受到塑料添加剂的影响[22],软塑料和泡沫塑料的再生塑料鉴定方法仍需进一步研究。硬塑料中再生聚乙烯、非再生聚乙烯和聚乙烯标准参考物质红外光谱图如图2所示,在2 920、2 850、1 470和720 cm-1等4处出现吸收峰,720 cm-1附近为聚乙烯的特征吸收峰。再生聚乙烯在3 400 cm-1附近区别于非再生塑料,出现弱吸收的宽幅吸收峰,对应分子间氢键O—H伸缩振动。

图1 硬塑料类(a)、软塑料类(b)和泡沫塑料类(c)玩具的材质

注:PS表示聚苯乙烯;PE表示聚乙烯;PTFE表示聚四氟乙烯;PP表示聚丙烯;ABS表示丙烯腈-丁二烯-苯乙烯共聚物;PVA表示聚乙烯醇;PVC表示聚氯乙烯;SBS表示苯乙烯-丁二烯-苯乙烯共聚物;PS表示聚苯乙烯;PU表示聚氨酯。

Fig. 1 Types of polymers in hard plastic (a), soft plastic (b) and foam plastic toys (c)

Note: PS means polystyrene; PE means polyethylene; PTFE means polytetrafluoroethylene; PP means polypropylene; ABS means acrylonitrile butadiene styrene; PVA means polyvinyl alcohol; PVC means polyvinyl chloride; SBS means styrene-butadiene-styrene; PS means polystyrene; PU means polyurethane.

图2 再生聚乙烯(a)、非再生聚乙烯(b)和聚乙烯标准参考物质(c)的红外光谱图

Fig. 2 Infrared spectrograms of recycled polyethylene (a), non-recycled polyethylene (b) and reference material of polyethylene (c)

2.2 玩具中的重金属含量与组成

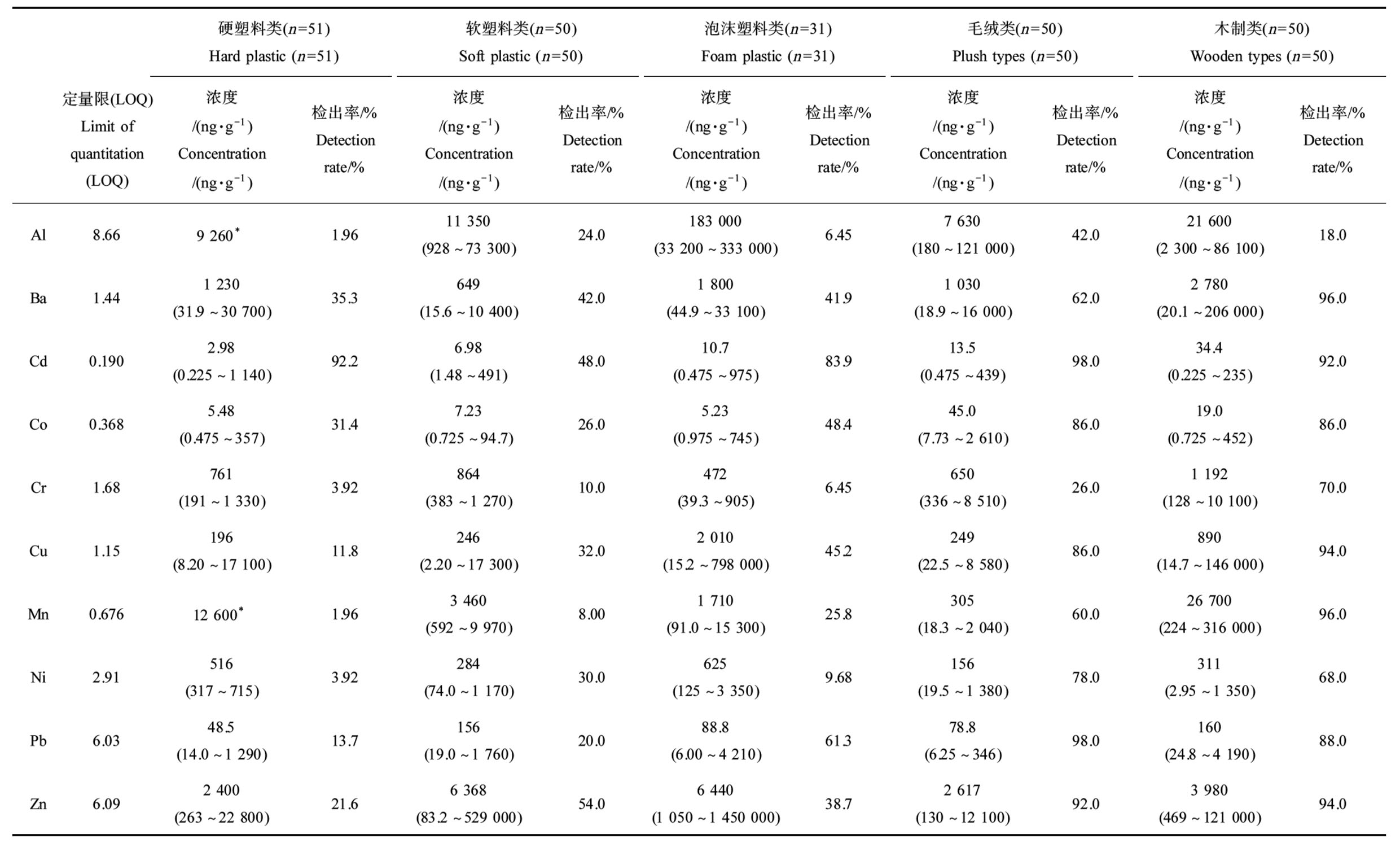

玩具中重金属浓度结果如表1所示。木制玩具和毛绒玩具中重金属检出率较高,样品中分别有7种和5种重金属的检出率超过80%。塑料玩具样品中重金属检出率相对较低,其中泡沫塑料玩具中只有Cd和Pb的检出率超过50%。而在硬塑料和软塑料玩具中分别仅有Cd和Zn的检出率超过50%。Guney和Zagury[13]的研究结果表明塑料玩具的金属检出率相比其他类型玩具更低。Borling等[23]发现泡沫塑料玩具的金属检出率处于较低水平,与本研究的结果相似。Korfali等[24]研究报道77%的塑料玩具样品中检出Zn和Cu,而Cr的检出率则超过90%。Zn在软塑料玩具中检出率较高的原因可能是Zn作为抗氧化剂和稳定剂广泛应用于热塑性塑料生产过程[25]。

研究结果与中华人民共和国国家标准(GB 6675.4—2014)[26]规定的迁移限值(Ba 1.00×106 ng·g-1,Cd 7.50×104 ng·g-1,Cr 6.00×104 ng·g-1,Pb 9.00×104 ng·g-1)相比,样品全部未超标。欧盟玩具安全条例(EN 71-3: 2019)[27]比我国安全标准提供了更多内容,如针对玩具材料定义不同限值。与欧盟标准相比,5类玩具的Cr浓度中值均超过欧盟规定有毒元素Cr(Ⅵ)迁移限值53.0 ng·g-1,其中木制玩具中Cr最高浓度达到1.01×103 ng·g-1,但均在Cr(Ⅲ)迁移限值4.60×105 ng·g-1内。本研究未分析Cr的形态,后续仍需对玩具中不同形态的Cr进行确切健康风险评估。![]() 和Frankowski[28]报道玩具中的Cr(Ⅲ)含量最高为2.32×103 ng·g-1,低于本研究。

和Frankowski[28]报道玩具中的Cr(Ⅲ)含量最高为2.32×103 ng·g-1,低于本研究。

除Cr外,玩具中其他重金属浓度均未超过欧盟标准限值,且至少低于规定值一个数量级,说明塑料、毛绒和木制玩具的重金属污染水平总体较低。Cd和Pb的最高浓度分别来自硬塑料和泡沫塑料玩具,分别为1 140 ng·g-1和4 210 ng·g-1。Borling等[23]发现泡沫塑料玩具中重金属浓度均未超标。在Guney和Zagury[13]研究中,金属玩具的重金属污染水平在各类玩具中最高,其中Pb的最高浓度为6.53×108 ng·g-1,超过欧盟限值几千倍。儿童珠宝塑料配件的As和Cd含量超过欧盟限量,分别达到2.07×105 ng·g-1和7.71×105 ng·g-1,推测是塑料配件与儿童珠宝生产过程中的共同污染[13]。本研究塑料玩具中Cu和Al浓度最高值来自泡沫塑料样品,分别为7.98×105 ng·g-1和3.33×105 ng·g-1,高于Korfali等[24]报道的塑料玩具中Cu(1.4×105 ng·g-1)和Al(9.85×104 ng·g-1)最高值。

玩具样品中重金属组成如图3所示,Zn在软塑料和泡沫玩具重金属中占比较高,在软塑料类重金属中占比70%。泡沫塑料玩具样品中Zn浓度最高值为1.45×106 ng·g-1,对总重金属含量的贡献最大。Al在毛绒玩具中重金属的占比达到50%,Mn在木制玩具中重金属的占比超过50%。

图3 玩具样品中重金属含量占比

Fig. 3 Compositions of heavy metals in toy samples

2.3 玩具中重金属含量差异与相关性

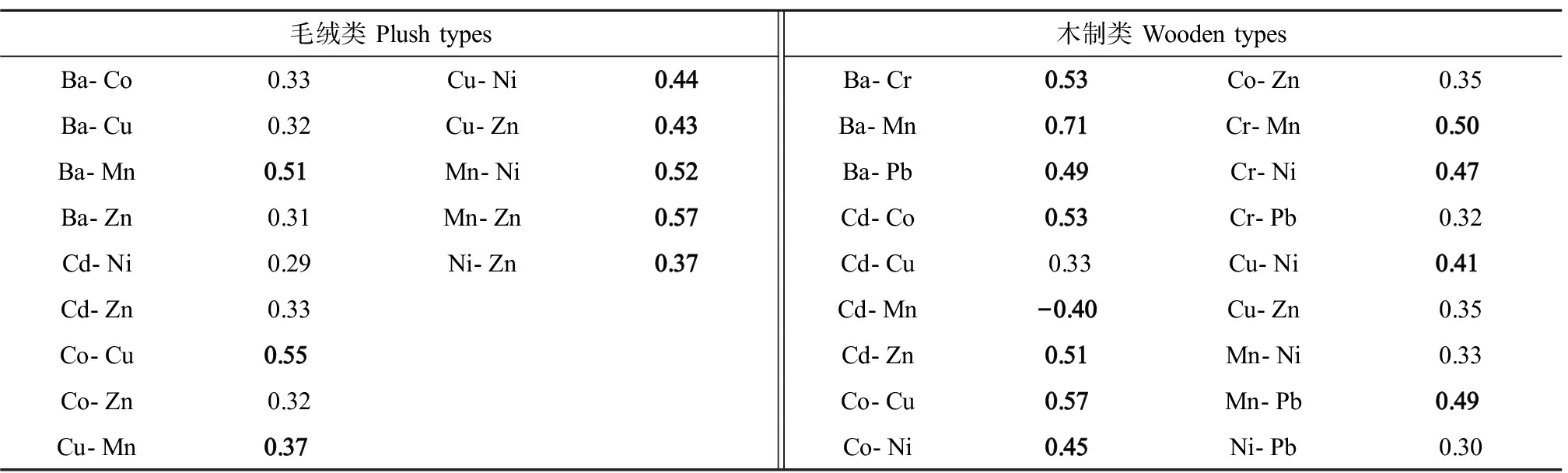

2.3.1 同类玩具的不同重金属含量相关性

通过Spearman检验对玩具样品中检出率>50%的重金属浓度间的关系进行分析(表2),在毛绒玩具和木制玩具中多种重金属浓度显著相关。木制玩具中的Ba-Mn存在较强正相关关系,相关系数(r)>0.7。木制玩具中的Cd-Mn存在负相关性,除此外均为正相关关系。

2.3.2 不同种类玩具同一重金属含量差异

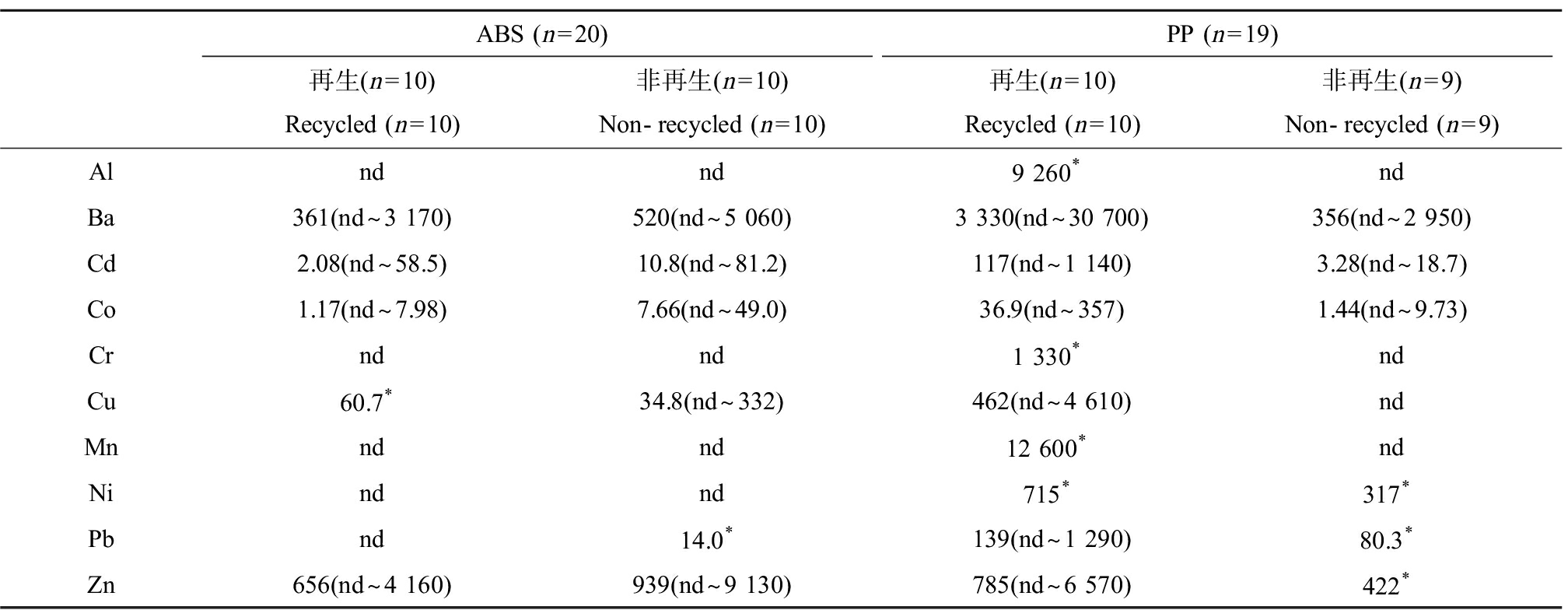

Kruskal-Wallis检验结果表明,硬塑料类和软塑料类玩具中不同塑料材质的重金属浓度不存在显著差异。泡沫类PE和PP材质玩具中的Cd和泡沫类PU和PE材质的Mn浓度存在显著差异(P<0.05)。再生与非再生硬塑料类玩具的重金属浓度如表3所示,ABS玩具中非再生塑料的Ba、Cd、Co、Cu和Zn均值浓度高于再生塑料。Eriksen等[29]发现再生塑料中Al、Pb、Ti和Zn浓度比原塑料更高。硬塑料中所有重金属的最高浓度均来自PP再生塑料。PP玩具中再生塑料的Ba、Cd和Co均值浓度高于再生塑料一个数量级以上,且再生塑料中所有重金属的检出率更高。PP类再生塑料中Cd和Pb均值浓度为117 ng·g-1和139 ng·g-1。通过Mann-Whitney U检验比较了ABS和PP硬塑料玩具中再生与非再生塑料间的同一重金属浓度,发现再生与非再生塑料中的10种重金属浓度均无显著差异,原因可能是不同样品个体中重金属浓度差异较大。已有的研究曾关注再生塑料与有机污染物残留的关系,有机污染物在塑料回收过程中可能降解或迁移,但重金属迁移较少[30],大部分仍残留于再生材料中[31]。本研究结果说明再生塑料比非再生塑料具有更高含量的重金属,使用再生塑料带来的生态安全和健康风险需要引起重视。

表1 玩具中重金属浓度(中值(范围))

Table 1 Concentrations of heavy metals in toys (median (range))

硬塑料类(n=51)Hard plastic (n=51)软塑料类(n=50)Soft plastic (n=50)泡沫塑料类(n=31)Foam plastic (n=31)毛绒类(n=50)Plush types (n=50)木制类(n=50)Wooden types (n=50)定量限(LOQ)Limit of quantitation (LOQ)浓度/(ng·g-1)Concentration/(ng·g-1)检出率/%Detection rate/%浓度/(ng·g-1)Concentration/(ng·g-1)检出率/%Detection rate/%浓度/(ng·g-1)Concentration/(ng·g-1)检出率/%Detection rate/%浓度/(ng·g-1)Concentration/(ng·g-1)检出率/%Detection rate/%浓度/(ng·g-1)Concentration/(ng·g-1)检出率/%Detection rate/%Al8.669 260*1.9611 350(928~73 300)24.0183 000(33 200~333 000)6.457 630(180~121 000)42.021 600(2 300~86 100)18.0Ba1.441 230(31.9~30 700)35.3649(15.6~10 400)42.01 800(44.9~33 100)41.91 030(18.9~16 000)62.02 780(20.1~206 000)96.0Cd0.1902.98(0.225~1 140)92.26.98(1.48~491)48.010.7(0.475~975)83.913.5(0.475~439)98.034.4(0.225~235)92.0Co0.3685.48(0.475~357)31.47.23(0.725~94.7)26.05.23(0.975~745)48.445.0(7.73~2 610)86.019.0(0.725~452)86.0Cr1.68761(191~1 330)3.92864(383~1 270)10.0472(39.3~905)6.45650(336~8 510)26.01 192(128~10 100)70.0Cu1.15196(8.20~17 100)11.8246(2.20~17 300)32.02 010(15.2~798 000)45.2249(22.5~8 580)86.0890(14.7~146 000)94.0Mn0.67612 600*1.963 460(592~9 970)8.001 710(91.0~15 300)25.8305(18.3~2 040)60.026 700(224~316 000)96.0Ni2.91516(317~715)3.92284(74.0~1 170)30.0625(125~3 350)9.68156(19.5~1 380)78.0311(2.95~1 350)68.0Pb6.0348.5(14.0~1 290)13.7156(19.0~1 760)20.088.8(6.00~4 210)61.378.8(6.25~346)98.0160(24.8~4 190)88.0Zn6.092 400(263~22 800)21.66 368(83.2~529 000)54.06 440(1 050~1 450 000)38.72 617(130~12 100)92.03 980(469~121 000)94.0

注:*代表唯一检出。

Note: *means the detection of only one sample.

2.4 健康风险评价

重金属日摄入量(daily intake, DI) (μg·kg-1·d-1)=(C×I×EF)/BW

(1)

式中:C是玩具中某重金属的含量(μg·g-1),I是儿童的口腔接触摄入量0.1 g·d-1[32],EF是暴露频率(1 d-1,一次暴露),BW是平均体质量。根据美国环境保护局(U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)发布的儿童特定因素暴露手册[32]标准,6~12月婴儿为9.2 kg。设定儿童接触玩具所摄入的重金属生物利用率为100%。

摄入元素的危害指数(hazard index, HI)=DI / RfD

(2)

式中:RfD是参考剂量(reference dose)。HI >1,视作高风险水平。

表2 玩具中重金属浓度之间的相关系数(P<0.05)

Table 2 Correlation coefficients between concentrations of heavy metals in toys (P<0.05)

毛绒类 Plush types木制类 Wooden typesBa-Co0.33Cu-Ni0.44Ba-Cr0.53Co-Zn0.35Ba-Cu0.32Cu-Zn0.43Ba-Mn0.71Cr-Mn0.50Ba-Mn0.51Mn-Ni0.52Ba-Pb0.49Cr-Ni0.47Ba-Zn0.31Mn-Zn0.57Cd-Co0.53Cr-Pb0.32Cd-Ni0.29Ni-Zn0.37Cd-Cu0.33Cu-Ni0.41Cd-Zn0.33Cd-Mn-0.40Cu-Zn0.35Co-Cu0.55Cd-Zn0.51Mn-Ni0.33Co-Zn0.32Co-Cu0.57Mn-Pb0.49Cu-Mn0.37Co-Ni0.45Ni-Pb0.30

注:“加粗”表示P<0.01,差异显著。

Note:“Bold” means P<0.01, significant difference.

表3 再生与非再生硬塑料类玩具的重金属浓度(平均值(范围))

Table 3 Concentrations of heavy metals in recycled and non-recycled hard plastic toys (average (range)) (ng·g-1)

ABS (n=20)PP (n=19)再生(n=10)Recycled (n=10)非再生(n=10)Non-recycled (n=10)再生(n=10)Recycled (n=10)非再生(n=9)Non-recycled (n=9)Alndnd9 260*ndBa361(nd~3 170)520(nd~5 060)3 330(nd~30 700)356(nd~2 950)Cd2.08(nd~58.5)10.8(nd~81.2)117(nd~1 140)3.28(nd~18.7)Co1.17(nd~7.98)7.66(nd~49.0)36.9(nd~357) 1.44(nd~9.73)Crndnd1 330*ndCu60.7*34.8(nd~332)462(nd~4 610)ndMnndnd12 600*ndNindnd715*317*Pbnd14.0*139(nd~1 290)80.3*Zn656(nd~4 160)939(nd~9 130)785(nd~6 570)422*

注:*代表唯一检出;nd代表未检出。

Note: *means the detection of only one sample; nd means not detectable.

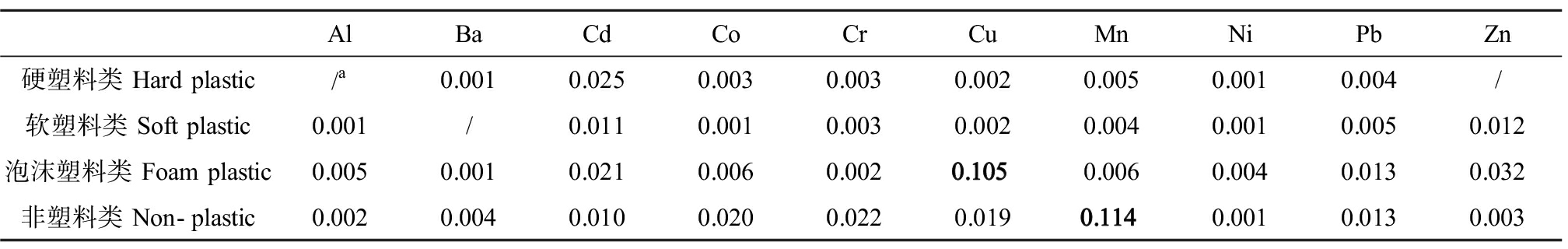

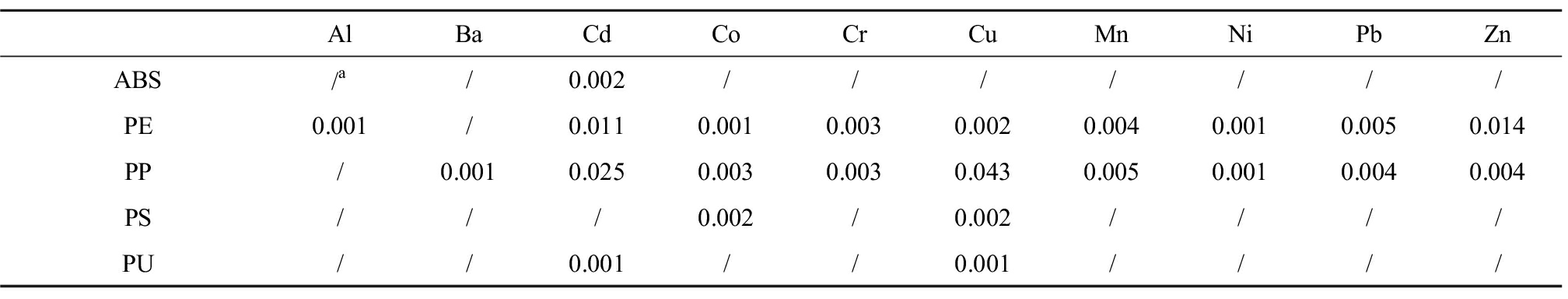

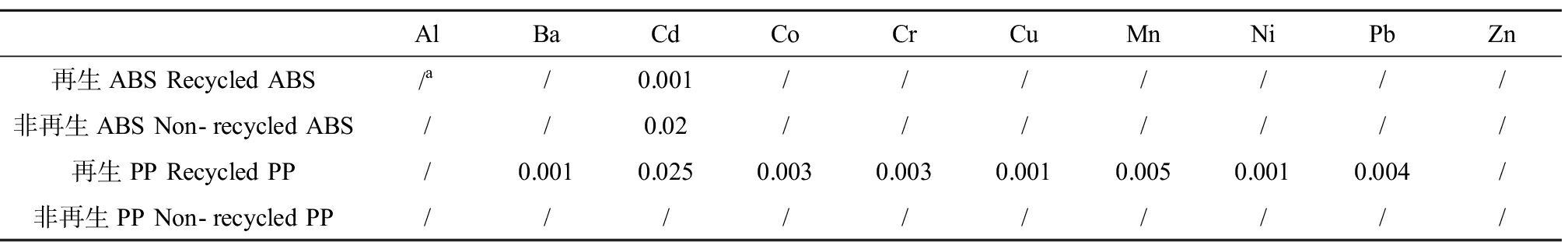

荷兰国家公共卫生和环境研究所报告[7]的儿童玩具中重金属RfD值为Al 750 μg·kg-1·d-1,Ba 600 μg·kg-1·d-1,Cd 0.500 μg·kg-1·d-1,Co 1.40 μg·kg-1·d-1,Cr 5.00 μg·kg-1·d-1,Cu 83.0 μg·kg-1·d-1,Mn 30.0 μg·kg-1·d-1,Ni 10.0 μg·kg-1·d-1,Pb 3.60 μg·kg-1·d-1,Zn 500 μg·kg-1·d-1。选择玩具样品中重金属浓度最高值代入式(1)和式(2)进行计算,以了解玩具可能带来的最高健康风险。为了解塑料材质和再生塑料使用带来的重金属暴露健康风险,本文分别列出了不同塑料类别(表4)、不同聚合物材质(表5)、再生和非再生硬塑料(表6)样品中的重金属危害指数。泡沫塑料的Cu和非塑料类的Mn对6~12月婴儿存在一定潜在风险。硬塑料的Cd,泡沫塑料的Cu、Pb和Zn,非塑料类的Co、Cr、Mn和Pb风险相对较高。PE的Zn,PP的Cd和Cu风险相对较高。硬塑料ABS和PP危害指数如表6所示,再生与非再生ABS健康风险近无。再生PP的Cd与非再生相比更高,整体上再生PP的潜在健康风险更大。其他HI均<0.05,表明塑料玩具、毛绒玩具和木制玩具样品中Al、Ba、Cd、Co、Cr、Ni、Pb和Zn对儿童造成的潜在风险较低。再生PP塑料玩具的潜在健康风险需要引起注意。

3 讨论(Discussion)

目前极少有研究关注玩具中塑料材质、再生塑料和重金属污染间的关系。本研究发现木制玩具和毛绒玩具中重金属检出率高于硬塑料和软塑料,其原因可能是重金属常被应用于玩具颜料和涂料中,较少用于玩具的添加剂。例如Cr主要应用于玩具的涂料中,而不会被直接添加进聚合物中[33]。Greenway和Gerstenberger[34]发现PVC玩具中Pb平均浓度为3.25×105 ng·g-1,非PVC玩具为8.90×104 ng·g-1。而Kang和Zhu[35]发现PVC和ABS玩具中Pb平均浓度分别为2.97×104 ng·g-1和1.02×105 ng·g-1。泡沫塑料玩具中PE的Cd和Mn的污染水平高于PP和PU,具体原因需进一步探究。PP类再生塑料玩具中多种重金属的含量高于非再生塑料玩具,但不具有显著差异。但仍需加强对再生塑料回收和生产过程中的环境污染物监管,杜绝已禁用的塑料添加剂重新“再生”进入新产品。玩具中的重金属风险评价危害指数均<1,说明上述玩具对儿童造成的潜在风险水平较低。值得注意的是,本研究的风险评估假设玩具中的重金属生物可利用度为1,未考虑重金属的皮肤渗透效率、在口腔和胃肠道的吸收效率等因素。有研究表明幼儿有非进食物品相关的高频率口腔行为[36],未来需留意唾液中玩具重金属的迁移,对不同塑料材质玩具中的环境污染物健康风险进行更细致的评估。

表4 基于玩具中重金属浓度最高值对婴儿的危害指数(HI)

Table 4 Hazard index (HI) values based on the maximum levels of metals in toys to infants

AlBaCdCoCrCuMnNiPbZn硬塑料类 Hard plastic/a0.0010.0250.0030.0030.0020.0050.0010.004/软塑料类 Soft plastic0.001/0.0110.0010.0030.0020.0040.0010.0050.012泡沫塑料类 Foam plastic0.0050.0010.0210.0060.0020.1050.0060.0040.0130.032非塑料类 Non-plastic0.0020.0040.0100.0200.0220.0190.1140.0010.0130.003

注:加粗表示0.1

Note: Bold means 0.1

表5 基于各材料玩具中重金属浓度最高值对婴儿的危害指数(HI)

Table 5 Hazard index (HI) values based on the maximum levels of metals in various toys to infants

AlBaCdCoCrCuMnNiPbZnABS/a/0.002///////PE0.001/0.0110.0010.0030.0020.0040.0010.0050.014PP/0.0010.0250.0030.0030.0430.0050.0010.0040.004PS///0.002/0.002////PU//0.001//0.001////

注:/a表示HI<0.001。

Note: /a means HI<0.001.

表6 基于再生与非再生硬塑料中重金属浓度最高值对婴儿的危害指数(HI)

Table 6 Hazard index (HI) values based on the maximum levels of metals in recycled and non- recycled hard plastic to infants

AlBaCdCoCrCuMnNiPbZn再生ABS Recycled ABS/a/0.001///////非再生ABS Non-recycled ABS//0.02///////再生PP Recycled PP/0.0010.0250.0030.0030.0010.0050.0010.004/非再生PP Non-recycled PP//////////

注:/a表示HI<0.001。

Note: /a means HI<0.001.

[1] 蔚青, 李巧玲, 李冰茹, 等. 北京市典型有机设施蔬菜基地重金属污染特征及风险评估[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2019, 14(3): 258-271

Yu Q, Li Q L, Li B R, et al. Heavy metal pollution characteristics and risk assessment of typical organic facility vegetable bases in Beijing [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2019, 14(3): 258-271 (in Chinese)

[2] Becker M, Edwards S, Massey R I. Toxic chemicals in toys and children’s products: Limitations of current responses and recommendations for government and industry [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(21): 7986-7991

[3] United States Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US ATSDR). Interaction profile for toxic substances: Lead, manganese, zinc, and copper [EB/OL]. (2020-11-04) [2021-07-05]. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/interactionprofiles/ip06.html

[4] United States Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US ATSDR). Interaction profile for toxic substances: Arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and lead [EB/OL]. (2020-11-04) [2021-07-05]. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/interactionprofiles/ip04.html

[5] Lanphear B P, Hornung R, Khoury J, et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: An international pooled analysis [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2005, 113(7): 894-899

[6] 周小勇, 雷梅, 杨军, 等. 某铅冶炼厂对周边土壤质量和人体健康的影响[J]. 环境科学, 2013, 34(9): 3675-3678

Zhou X Y, Lei M, Yang J, et al. Effect of lead on soil quality and human health around a lead smeltery [J]. Environmental Science, 2013, 34(9): 3675-3678 (in Chinese)

[7] VanEngelen J G M, Park M V D Z, Janssen P J C M, et al. Chemicals in toys, a general methodology for assessment of chemical safety of toys with a focus on elements, RIVM report 320003001/2008 [R]. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment and Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, 2008

[8] 赵红军, 格鹏飞, 常旭红, 等. 镍的生理毒代动力学模型[J]. 卫生研究, 2017, 46(5): 797-801

Zhao H J, Ge P F, Chang X H, et al. Physiologically based toxicokinetic model for nickel [J]. Journal of Hygiene Research, 2017, 46(5): 797-801 (in Chinese)

[9] Yost L, Tao S, Egan S K, et al. Estimation of dietary intake of inorganic arsenic in US children [J]. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, 2004, 10(3): 473-483

[10] Sexton K, Adgate J L, Fredrickson A L, et al. Using biologic markers in blood to assess exposure to multiple environmental chemicals for inner-city children 3-6 years of age [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(3): 453-459

[11] Guney M, Zagury G J. Heavy metals in toys and low-cost jewelry: Critical review of US and Canadian legislations and recommendations for testing [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(8): 4265-4274

[12] Babich M A, Bevington C, Dreyfus M A. Plasticizer migration from children’s toys, child care articles, art materials, and school supplies [J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2020, 111: 104574

[13] Guney M, Zagury G J. Contamination by ten harmful elements in toys and children’s jewelry bought on the North American market [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(11): 5921-5930

[14] Aurisano N, Huang L, Milà i Canals L, et al. Chemicals of concern in plastic toys [J]. Environment International, 2021, 146: 106194

[15] Dahab A A, Elhag D E A, Ahmed A B, et al. Determination of elemental toxicity migration limits, bioaccessibility and risk assessment of essential childcare products [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(4): 3406-3413

[16] Cui X Y, Li S W, Zhang S J, et al. Toxic metals in children’s toys and jewelry: Coupling bioaccessibility with risk assessment [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 200: 77-84

[17] Guney M, Zagury G J. Children’s exposure to harmful elements in toys and low-cost jewelry: Characterizing risks and developing a comprehensive approach [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014, 271: 321-330

[18] Akimzhanova Z, Guney M, Kismelyeva S, et al. Contamination by eleven harmful elements in children’s jewelry and toys from Central Asian market [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2020, 27(17): 21071-21083

[19] Cherif Lahimer M, Ayed N, Horriche J, et al. Characterization of plastic packaging additives: Food contact, stability and toxicity [J]. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2017, 10: S1938-S1954

[20] Geyer R, Jambeck J R, Law K L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made [J]. Science Advances, 2017, 3(7): e1700782

[21] Tran O T K, Luong T T, Tran H N, et al. Determination of phthalate esters in children’s toys [J]. Science and Technology Development Journal, 2016, 19(3): 79-88

[22] Karlsson S. Recycled polyolefins. Material properties and means for quality determination [J]. Advances in Polymer Science, 2004, 169: 201-229

[23] Borling P, Engelund B, Sørensen H, et al. Survey, migration and health evaluation of chemical substances in toys and childcare products produced from foam plastic [R]. Odense: Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2006

[24] Korfali S I, Sabra R, Jurdi M, et al. Assessment of toxic metals and phthalates in children’s toys and clays [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2013, 65(3): 368-381

[25] Hahladakis J N, Velis C A, Weber R, et al. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 344: 179-199

[26] 国家质量监督检验检疫总局, 中国国家标准化管理委员会. 玩具安全 第4部分: 特定元素的迁移: GB 6675.4—2014[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2016

[27] European Committee for Standardization. EN 71-3: 2019 environmental standards [S]. Brussels: CEN-CENELEC Management Centre, 2019

![]() K, Frankowski M. Analysis of hazardous elements in children toys: Multi-elemental determination by chromatography and spectrometry methods [J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(11): 3017

K, Frankowski M. Analysis of hazardous elements in children toys: Multi-elemental determination by chromatography and spectrometry methods [J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(11): 3017

[29] Eriksen M K, Pivnenko K, Olsson M E, et al. Contamination in plastic recycling: Influence of metals on the quality of reprocessed plastic [J]. Waste Management, 2018, 79: 595-606

[30] Whitt M, Brown W, Danes J E, et al. Migration of heavy metals from recycled polyethylene terephthalate during storage and microwave heating [J]. Journal of Plastic Film & Sheeting, 2016, 32(2): 189-207

[31] Hansen E, Nilsson N H, Lithner D, et al. Hazardous substances in plastic materials [R]. Vejle: COWI and Danish Technological Institute, 2013

[32] US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Child-specific exposure factors handbook: EPA/600/R-06/096F [R]. Washington DC: Office of Research and Development, 2008

[33] Soares E P, Saiki M, Wiebeck H. Determination of inorganic constituents and polymers in metallized plastic materials [J]. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 2005, 264(1): 9-13

[34] Greenway J A, Gerstenberger S. An evaluation of lead contamination in plastic toys collected from day care centers in the Las Vegas valley, Nevada, USA [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2010, 85(4): 363-366

[35] Kang S G, Zhu J X. Total lead content and its bioaccessibility in base materials of low-cost plastic toys bought on the Beijing market [J]. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 2015, 17(1): 63-71

[36] Tulve N S, Suggs J C, McCurdy T, et al. Frequency of mouthing behavior in young children [J].Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2002, 12(4): 259-264