随着抗生素在医疗卫生、畜牧养殖等领域大规模的使用,给人类疾病治疗及动植物生产养殖方面带来便利的同时,大量残留的抗生素及耐药基因也随之被检出,导致细菌耐药性的产生[1-2],尤其是具有多重耐药的“超级细菌”。联合国粮食及农业组织(Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO)、世界动物卫生组织(World Organization for Animal Health, OIE)和世界卫生组织(World Health Organization, WHO)均认为抗生素耐药性的出现加剧了世界各地对细菌感染性疾病的治疗难度,已成为当前全球卫生、食品安全和发展面临的最紧迫的威胁之一[3-4]。

正常肠道菌群处于动态平衡状态,理想比例为益生菌∶致病菌∶条件致病菌=2∶1∶7[5]。益生菌进入肠道后会迅速繁殖,并与其他致病菌或条件致病菌竞争所需要的营养及空间,还可主动分泌抗菌物质,起到调节肠道平衡的作用。正常情况下,肠道内的条件致病菌对人体健康并无有害影响,但当宿主个体免疫功能低下时,肠道中的条件致病菌或致病菌将引起严重的食源性疾病。食源性疾病是指食用被食源性病原体或其毒素污染的食物或水引起的疾病,食源性病原体主要包括病毒、细菌、真菌和寄生虫等[6],其广泛存在于肉制品、奶制品、新鲜果蔬和腌菜等各种食物中,而细菌则是导致中毒和死亡的主要原因。目前,常见的食源性致病菌多为条件致病菌,主要有致病性大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、沙门氏菌(Salmonella)、李斯特菌(Listeria)、副溶血性弧菌(Vibrio parahaemolyticus)、金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)和肉杆菌(Carnobacterium)等[7]。欧洲食品安全局(European Food Safety Authority, EFSA)、欧洲疾病预防控制中心(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, ECDC)报道指出,在水果蔬菜等多种食品中检出了条件致病菌,且可对大多数广谱抗生素产生耐药性[8]。Liao等[9]从一批菠菜中筛出了假单胞菌(Pseudomonas)、肠杆菌(Enterobacter)和不动杆菌(Acinetobacter)等共8种细菌,且大部分都属于多重耐药菌。Liu等[10]在包括肉制品、乳制品、水果蔬菜及甜点在内的42份样品中均筛选出了金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus),其中21株具有多重耐药性。Kim等[11]在韩国197份即食性样品中筛到了金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)。多数情况下条件致病菌通过食物的摄取进入人体肠道,导致肠道菌群失调从而影响人体免疫系统等功能,引发如肥胖[12]、糖尿病[13-14]和类风湿性关节炎[15-16]等疾病。根据美国疾病控制和预防中心(Center for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC)报告,美国每年大约有3 000人死于食源性疾病[17]。因此,对食品中细菌耐药性问题的研究乃是当务之急。

新鲜农产品作为公认的营养和健康饮食的重要组成部分,已成为人类每天不可或缺的“能量源”[18],然而自20世纪90年代中期以来,国际上爆发的与新鲜农产品有关的食源性疾病越来越多[19],食用受病原菌污染的新鲜果蔬导致16个国家发生了4 000多起食源性疾病,多数人患有溶血性尿毒综合症,导致54人肾功能衰竭[20]。2011年德国爆发的“毒黄瓜”事件,则是由肠出血性大肠杆菌(Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli)引起的,研究发现该菌株携带着氨基糖苷类、大环内酯类和磺胺类等抗生素耐药基因,有专家认为新鲜果蔬是肠出血性大肠杆菌(EHEC)疫情爆发时细菌传播的载体之一[21]。美国爆发全国性的“毒西红柿”疫情则是由产自墨西哥和美国佛罗里达州的西红柿感染沙门氏菌(Salmonella)导致的。因此,新鲜果蔬受到各种病原体的污染已被认为是当前重大的食品安全问题之一[22],然而,迄今为止,关于新鲜果蔬中病原菌致病机制的研究仍然较少,因此对新鲜果蔬中细菌的分布特征及致病菌耐药性研究已是当务之急,以确保安全的食品供应和最大限度地减少食源性疾病的发生。本文购买了6种新鲜果蔬样品,基于可培养细菌的筛选及与肠道疾病相关致病菌的抗生素耐药性分析,对华北地区冬季新鲜果蔬中细菌的分布特征及致病菌的抗生素耐药性状况进行了研究,以期更好地揭示人体肠道菌群中耐药菌的来源,为人体健康风险评估及食源性耐药菌的防治提供理论数据和科学依据。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 材料与试剂

1.1.1 样品来源及预处理

于2020年12月在华北地区某集市购买6种新鲜果蔬样品,包括苹果、香蕉、草莓、葡萄、番茄和黄瓜。将购买的样品保存于无菌密封袋中,并于12 h内在实验室进行预处理。采用蒸馏水清洗3次,以清除果蔬表面灰尘及土壤中携带的细菌,达到正常食用标准[23]。随后称取25 g[24]洗净样品于无菌研钵中研磨至糊状后置于50 mL无菌离心管中,并添加30 mL PBS缓冲液[25],涡旋10 min以充分混匀,放入4 ℃冰箱以备后续实验的使用。

1.1.2 主要试剂

培养基类:伊红美蓝琼脂培养基、SS琼脂培养基、TCBs琼脂培养基、甘露醇高盐琼脂培养基、绵羊血琼脂培养基、气单胞菌培养基、十六烷三甲基溴化铵琼脂培养基、麦康凯琼脂培养基、麦康凯肌醇阿东醇羧苄青霉素培养基和MH培养基,以上培养基均购自天津所罗门生物科技有限公司。

抗生素类:氨苄青霉素(ampicillin, AMP)、庆大霉素(gentamicin, GEN)、红霉素(erythromycin, ERY)、多粘菌素B(polymyxin B, PB)、环丙沙星(ciprofloxacin, CIP)、磺胺甲恶唑(sulfamethoxazole, SMZ)、四环素(tetracycline, TET)和头孢他啶(ceftazidime, CAZ),以上抗生素均购自天津恒山化工科技有限公司。

其他:酵母提取物、蛋白胨、PBS缓冲液、琼脂粉、氯化钠和甘油均购自天津鼎国生物技术有限公司。

1.2 仪器与设备

超净工作台(VS-1302L-U,上海仪天科学仪器有限公司,中国);恒温培养箱(DHP-9082,上海海向仪器设备厂,中国);恒温摇床(SPH-2102C,上海世平实验设备有限公司,中国);高压灭菌锅(G180TW,致微仪器有限公司,中国);高速离心机(Centrifuge 5810R,Eppendrof,德国);涡旋振荡器(QL-901,海门市其林贝尔仪器公司,中国);酶标仪(SP-Max2300A2,上海闪谱生物科技有限公司,中国);移液枪(2.5 μL、10~1 000 μL、5 000 μL,Eppendrof,德国)。

1.3 实验方法

1.3.1 可培养细菌分离鉴定

经预处理后的样品用于可培养细菌的分离鉴定。按照培养基配方,分别配制选择性培养基和普通LB固体/液体培养基,并在121 ℃下高压灭菌20 min。将预处理后的样品利用PBS缓冲液进行稀释[26],取100 μL合适梯度的样品涂布于固体培养基上,于(36±1) ℃恒温培养箱过夜培养[27]。挑取大小、颜色、形态不同的菌落进行纯化,将获得的纯菌接种到3.5 mL LB液体培养液,置于(36±1) ℃恒温摇床过夜培养。取1 mL新鲜菌液保存于30% (V(甘油)∶V(水)=24 mL∶56 mL)甘油中并放入-80 ℃超低温冰箱保存,另取2 mL新鲜菌液采用TIANamp细菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒(TIANGEN,北京,中国)提取细菌DNA,并利用NanoPhotometer® N60 (IMPLEN,德国)进行DNA浓度和质量的检测后使用16S rRNA通用引物27F(5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’)和1492R(5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’)进行PCR扩增,将扩增后的PCR产物送至深圳华大基因股份有限公司进行PCR扩增子测序,测序结果通过NCBI网站(https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi)进行分析。将测得的序列复制到“Enter Query Sequence”选项框中,采用GeneBank数据库中的比对工具Nucleotide BLAST进行比对,选取“Max Score”和“Query Cover”值最高的为该序列所对应的菌株。

1.3.2 细菌抗生素耐药性分析

6种新鲜果蔬中筛选出了极易引起呼吸道及胃肠道疾病感染的条件致病菌和可用于植物疾病治疗及土壤防治的益生菌,挑选其中致病性较强的10株条件致病菌和2株应用较为广泛的益生菌进行抗生素耐药性分析,并进一步比较条件致病菌与益生菌间耐药性的差异。选取8种抗生素,庆大霉素(GEN)、红霉素(ERY)、多粘菌素B(PB)、环丙沙星(CIP)、磺胺甲恶唑(SMZ)、四环素(TET)、氨苄青霉素(AMP)和头孢他啶(CAZ),采用微量肉汤稀释法[28]对挑选出的12株菌种进行耐药性检测。分别配制1 024 mg·L-1抗生素,使用无菌注射器将配制好的抗生素溶液通过0.22 μm滤膜进行过滤处理,置于-20 ℃避光保存,以备后续使用。配制MH及LB液体培养基,将选定的12株菌进行活化处理并稀释至0.5个麦氏浊度[29]。96孔板的1~11列分别加入100 μL MH培养液,12列加入200 μL MH培养液,取不同种抗生素100 μL(1 024 mg·L-1)加至96孔板第1列,2~10列逐级稀释至512、256、128、64、32、16、8、4、2和1 mg·L-1,1~11列加100 μL菌液,即11列为阳性对照,12列为阴性对照[30]。将处理好的96孔板置于(36±1) ℃恒温培养箱过夜培养,用酶标仪测其OD600。

1.3.3 数据处理

采用Microsoft Excel 2010进行数据的处理及计算,并使用Origin 2021绘图。

2 结果与讨论(Results and discussion)

2.1 新鲜果蔬中益生菌的分离与鉴定

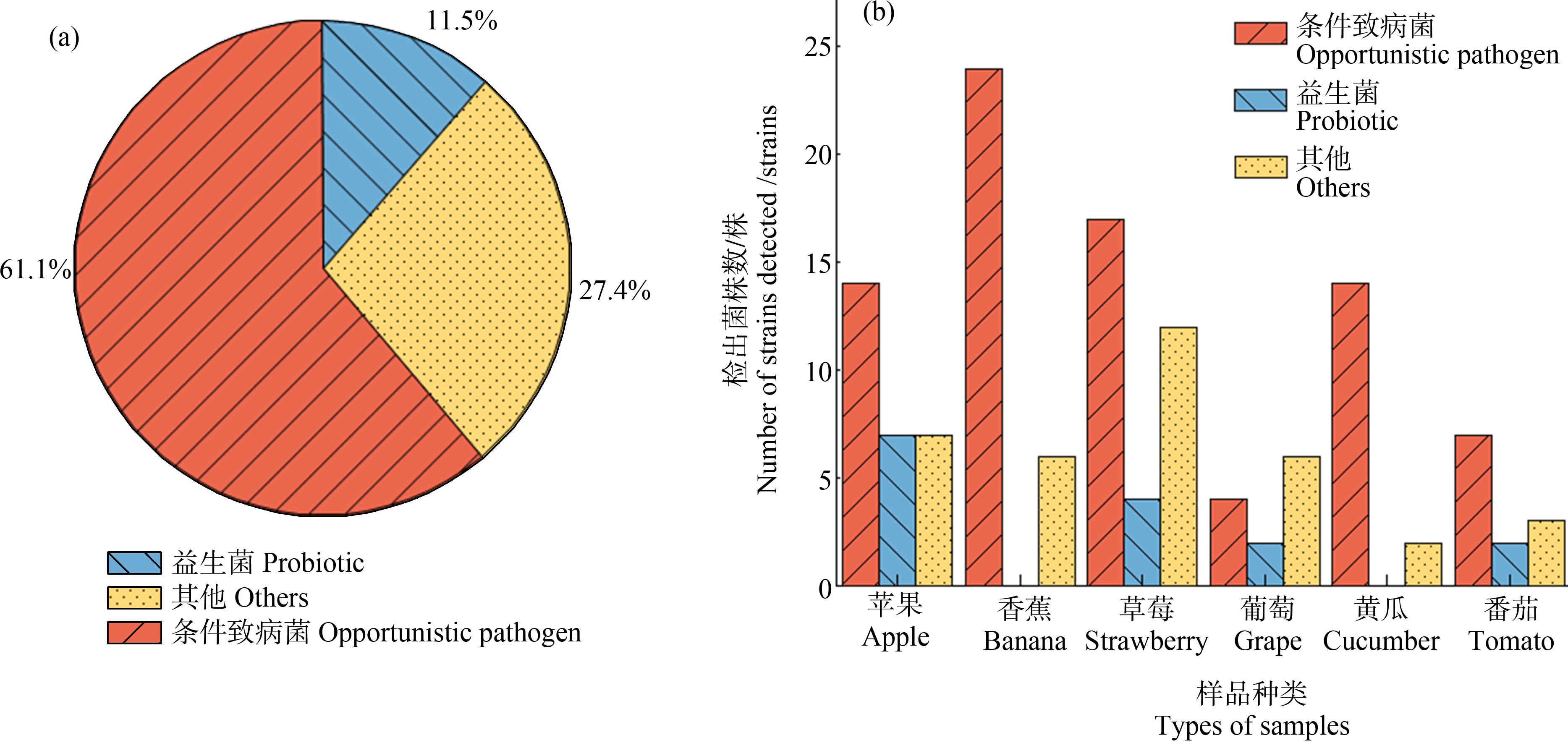

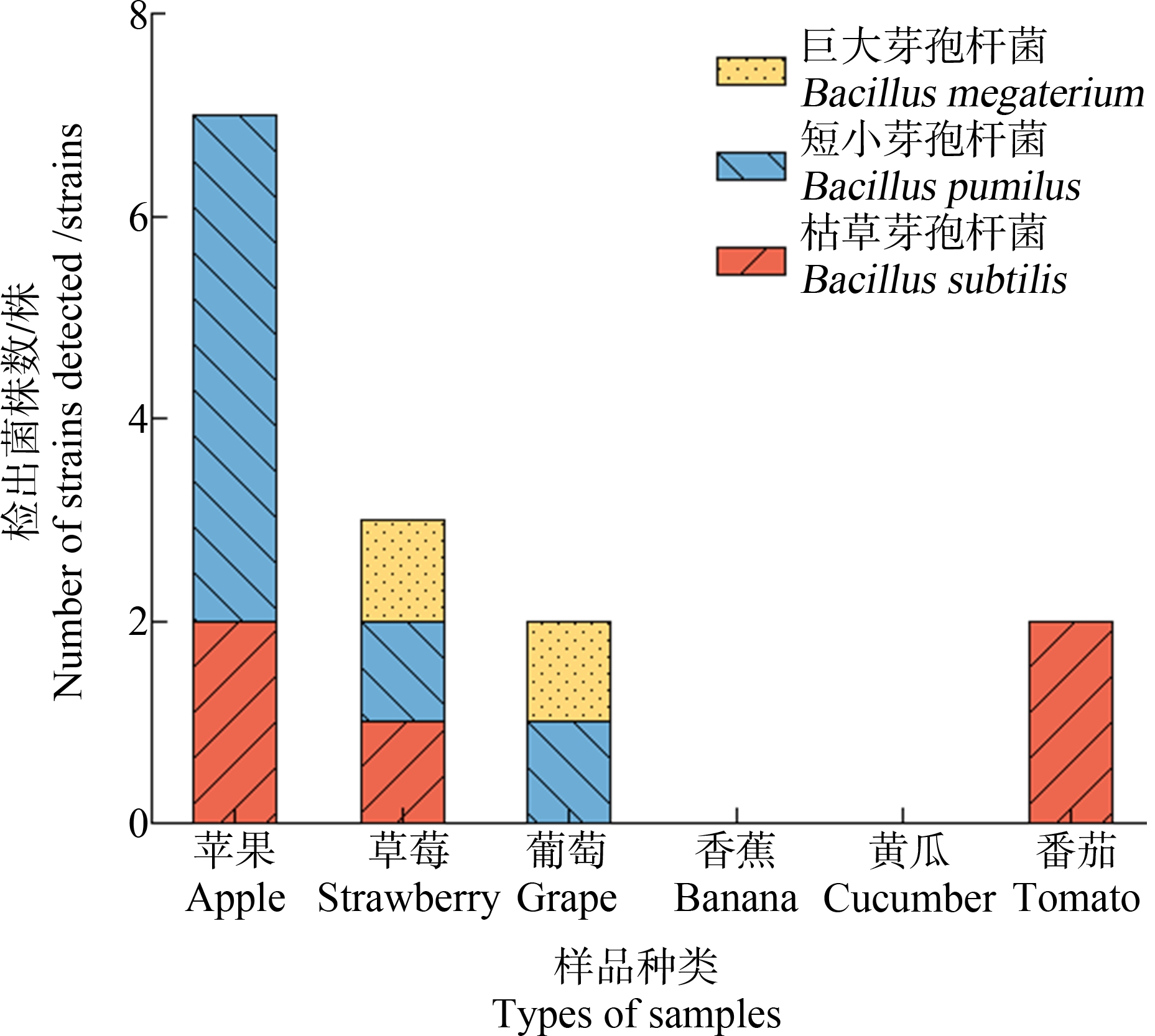

6种新鲜果蔬中共分离得到270株细菌,挑选形状、颜色和大小不同的131株鉴定比对,检出类型可分为益生菌(11.5%)、条件致病菌(61.1%)、其他(27.4%)三大类(图1(a))。6种新鲜果蔬中共检出15株益生菌,类型包括枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)、巨大芽孢杆菌(Bacillus megaterium)和短小芽孢杆菌(Bacillus pumilus)(图2),黄瓜中检出的细菌总数要高于番茄,但并无益生菌检出,只在番茄中检出枯草芽孢杆菌(B. subtilis)。4种水果样品中共检出26种103株细菌,其中益生菌占12.6%,相较于葡萄、草莓和香蕉而言,苹果中检出的益生菌数最多,以短小芽孢杆菌(B. pumilus)为主(图2)。而香蕉中并无益生菌的检出(图1(b))。益生菌可以防治果蔬在生长发育过程中的疾病,如短小芽孢杆菌(B. pumilus)可以抑制黄瓜枯萎病[31],也可有效控制草莓黑腐病[32],枯草芽孢杆菌(B. subtilis)对黄瓜的根系及果实也有防治作用[33]。在果蔬种植过程中,常使用益生菌制作堆肥,在肥料发酵的过程中,益生菌迅速繁殖,产生多种代谢产物,促使农作物的生长发育,增强农作物耐寒抗旱、抗病的能力,预防病虫等的危害。此外,益生菌作用于农作物的果实、叶片等部位还可延长其储藏保鲜时长。益生菌作为抗生素替代物之一,可防治作物各种疾病,提高作物产量的同时,也可维持胃肠道菌群平衡,调节宿主免疫系统,如通过摄取新鲜果蔬使得益生菌进入人体,在胃肠道内定植,产生消化酶,分泌抗菌代谢物,并迅速繁殖与其他致病菌竞争所需的空间及营养,抑制致病菌的生长繁殖[34-35],有助于维持肠道微生物的平衡。健康人体摄入益生菌后,可补充肠道菌群中益生菌的数量,促进肠道内营养物质的消化、吸收和代谢,控制人体质量,预防和缓解慢性疾病,增强人体健康。

图1 新鲜果蔬中细菌种类检出频率(a)与不同果蔬中细菌检出类型及丰度(b)

Fig. 1 Frequency of bacterial species in fresh fruits and vegetables (a), and the abundance of bacteria in fresh fruits and vegetables (b)

2.2 新鲜果蔬中条件致病菌的分离与鉴定

6种新鲜果蔬中共鉴定出80株条件致病菌,占比61.1%(图1(a))。黄瓜中检出条件致病菌占比66.67%,主要为恶臭假单胞菌(Pseudomonas putida)(37.5%)、大肠杆菌(E. coli)(12.5%)、绿色气球菌(Aerococcus viridans)(12.5%)和弗氏柠檬酸盐杆菌(Citrobacter freundii)(6.25%)(图3),番茄中检出的条件致病菌占比58.33%,主要为大肠杆菌(E. coli)(42.9%)、泛菌(Pantoea)(42.9%)和梭状芽孢杆菌(Bacillus fusiformis)(14.29%)。水果中鉴定出条件致病菌59株,占57.28%,其中香蕉中检出数最多(图1(b)),多为泛菌(Pantoea)(43.3%)、大肠杆菌(E. coli)(13.3%)、嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌(Stenotrophomonass maltophilia)(10%)、恶臭假单胞菌(P. putida)(10%)和肺炎克雷伯菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae)(3%),均可引起呼吸道及胃肠道细菌感染。由于致病菌与益生菌间存在着生态竞争关系,黄瓜、香蕉中条件致病菌的高检出率可能是导致益生菌未检出的原因之一。草莓中检出的条件致病菌占28.8%,主要为大肠杆菌(E. coli)(36.4%)、蕈状芽孢杆菌(Bacillus mycoides)(9%)和蜡样芽孢杆菌(Bacillus cereus)(6%),由于草莓表面的特殊结构,使其更容易携带病原体[36];苹果中检出条件致病菌占23.7%,主要为大肠杆菌(E. coli)(39.3%)、蜡样芽孢杆菌(B. cereus)(7.1%)和表皮葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus epidermidis)(3.6%);葡萄中检出条件致病菌仅占6.8%,以大肠杆菌(E. coli)为主,检出率为25%。大肠杆菌(E. coli)在6种果蔬样品中均有检出,是人和动物体内常见的寄生菌,多数不具有致病性,但仍有少数大肠杆菌可引起食源性疾病的爆发[37-38]。美国每年爆发的与大肠杆菌(E. coli)有关的食源性疾病多数都是由于食用新鲜农产品引起的[39],据报道,肠杆菌科细菌是通过食用新鲜农产品而导致胃肠道感染的主要病原体或机会病原体之一[40]。

图2 新鲜果蔬中益生菌检出种类及数目

Fig. 2 Species and number of probiotics in fresh fruits and vegetables

图3 新鲜果蔬中条件致病菌检出丰度

Fig. 3 Abundance of opportunistic pathogen in fresh fruits and vegetables

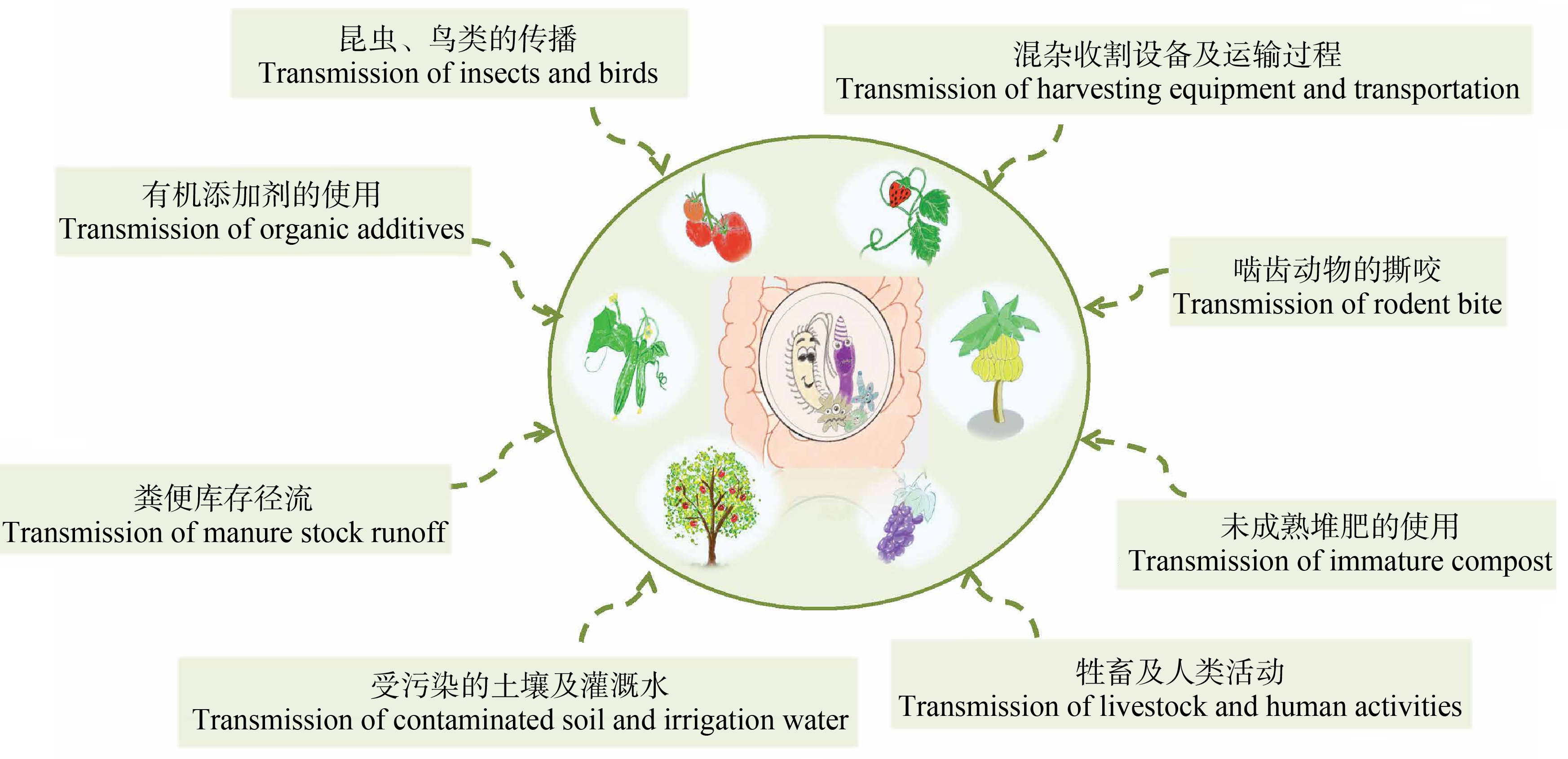

新鲜果蔬中条件致病菌来源较为广泛(图4)。研究表明,接触到地面的叶子比没有接触地面的叶子更容易受到致病菌的污染[41]。草莓生长高度较低,受污染的土壤及灌溉水、啮齿动物的撕咬可能是条件致病菌传播到草莓的主要途径;香蕉树属于多叶草本植物,叶片比表面积较大,表面常附着多种食源性致病菌,包括大肠杆菌(E. coli)、沙门氏菌(Salmonella)和金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)等,叶片上附着的细菌很有可能通过水平传播等方式使得香蕉果肉获得致病菌[42]。此外,也有研究表明,多叶草本植物受污染最为严重[43];苹果长势较高,昆虫、鸟类的传播可能是导致苹果中携带条件致病菌的原因[44],除此之外,牲畜及人类活动、未成熟堆肥的施用、来自农场堆肥和粪便库存的径流、有机添加剂不合理的使用、混杂收割设备的接触及运输过程等都可成为新鲜果蔬中条件致病菌的来源途径[45]。新鲜果蔬的摄入使条件致病菌传播至人体内,破坏肠道内原有的生态平衡,导致肠道菌群失调,从而引发各种疾病,如肥胖、高血压、自闭症、抑郁症、类风湿性关节炎和癌症等,对人体健康造成威胁。因此,对食源性致病菌的预防及治疗迫在眉睫。

图4 新鲜果蔬中耐药菌的可能来源

Fig. 4 Source of antibiotic resistance bacteria in fresh fruits and vegetables

2.3 新鲜果蔬中细菌抗生素耐药性分析

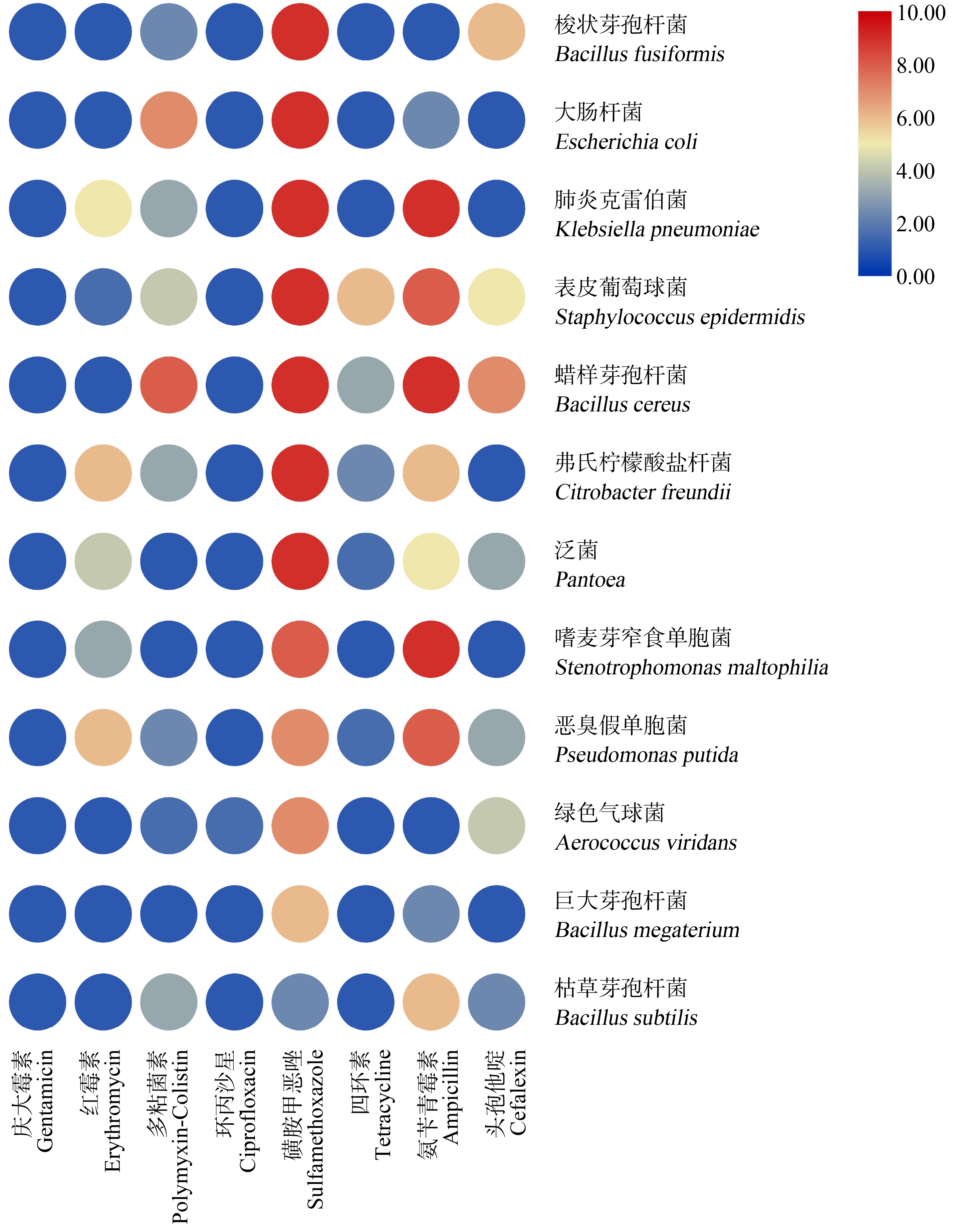

对6种新鲜果蔬中挑选的10株条件致病菌及2株益生菌进行抗生素耐药表型检测,结果表明(图5),12株菌对庆大霉素(GEN)和环丙沙星(CIP)均敏感,8株条件致病菌对磺胺甲恶唑(SMZ)表现出高耐药性,磺胺甲恶唑(SMZ)对7株(70%)条件致病菌的抑菌浓度高于512 mg·L-1,分别为梭状芽孢杆菌(B. fusiformis)、大肠杆菌(E. coli)、肺炎克雷伯菌(K. pneumoniae)、表皮葡萄球菌(S. epidermidis)、蜡样芽孢杆菌(B. cereus)、弗氏柠檬酸盐杆菌(C. freundii)和泛菌(Pantoea);对嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌(S. maltophilia)的抑菌浓度高于256 mg·L-1;对恶臭假单胞菌(P. putida)和绿色气球菌(A. viridans)的抑菌浓度高于128 mg·L-1。磺胺类抗生素作为各领域使用频率最高的化学物质,其原药或代谢产物通过多种途径进入水体、土壤等环境,由于其难降解性,在土壤中长期富集,随之进入蔬菜水果等植物中[46],这可能是多种条件致病菌对磺胺甲恶唑(SMZ)均表现出高耐药性的原因。5株条件致病菌对氨苄青霉素(AMP)的耐药性高于256 mg·L-1,其中3株高于512 mg·L-1,分别为肺炎克雷伯菌(K. pneumoniae)、蜡样芽孢杆菌(B. cereus)和嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌(S. maltophilia)。部分菌株对红霉素(ERY)、多粘菌素B(PB)、四环素(TET)和头孢他啶(CAZ)表现出较高的耐药性,可能是由于四环素类、β-内酰胺类和大环内酯类抗生素广泛应用于畜牧养殖及农药中[47],因在果蔬种植过程中大量使用含有抗生素的杀虫剂及动物有机肥,使得残留的抗生素或其代谢产物进入土壤富集[48],通过水平传播使得果蔬中残留抗生素或其代谢产物,在抗生素的压力下,部分敏感菌死亡,对抗生素具有耐药性的菌株不断生长繁殖,进行垂直传播,产生同样具有耐药性的后代[49]。10株条件致病菌中6株表现为多重耐药,分别为肺炎克雷伯菌(K. pneumoniae)、表皮葡萄球菌(S. epidermidis)、蜡样芽孢杆菌(B. cereus)、弗氏柠檬酸盐杆菌(C. freundii)、嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌(S. maltophilia)和恶臭假单胞菌(P. putida)。而枯草芽孢杆菌(B. subtilis)和巨大芽孢杆菌(B. megaterium)作为益生菌,对大多数抗生素均表现为敏感。磺胺甲恶唑(SMZ)对巨大芽孢杆菌(B. megaterium)的抑菌浓度也较其他条件致病菌低,为64 mg·L-1。枯草芽孢杆菌(B. subtilis)对氨苄青霉素(AMP)耐药性相对较高,为64 mg·L-1,对其他7种抗生素均敏感。相较于益生菌而言,条件致病菌更易获得耐药性,对人体健康产生威胁。

图5 抗生素对新鲜果蔬中细菌的最小抑菌浓度(MIC)

Fig. 5 Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotic on bacteria in fresh fruits and vegetables

长期食用携带食源性耐药菌的新鲜果蔬可破坏正常肠道微生物组的稳定性,破坏人体内自然防御机制,并诱发各种临床症状,若此时长期暴露于抗生素环境下,使病原菌中耐药基因增殖传播,给疾病的治疗带来一定的困难[50]。同时,抗生素的选择性压力将会造成肠道菌群失调,还可诱导其他条件病原菌繁殖,甚至通过水平基因转移获得耐药基因,诱发更严重的并发症。除此之外,肠道菌群中耐药菌及其携带的耐药基因也可通过排泄物等形式释放到环境中,进入水体、空气和土壤等介质,最终以食物链的形式进行循环传播,对人体健康及生态环境造成潜在风险。

综上所述,本文揭示了新鲜果蔬中细菌的分布特征及耐药菌的流行状况,进一步分析了肠道菌群中耐药菌的可能来源。在后续的研究中,可以增加样本量并考虑对新鲜果蔬中不可培养细菌及其耐药性进行研究,以全面揭示新鲜果蔬的摄入对人体健康存在的潜在风险。此外,还需考虑新鲜果蔬中杀虫剂或其他抗生素添加剂的残留及果蔬中如根、茎、叶和果实等各部位致病菌的分布及耐药性,并考虑对新鲜果蔬中致病菌在胃肠道内的定植规律及存活情况进行研究,有助于后续为食源性耐药菌来源分析提供全方位的理论性数据,并为食源性耐药菌的防治及人体健康风险的正确评估提供科学依据。

[1] le Page G, Gunnarsson L, Snape J, et al. Integrating human and environmental health in antibiotic risk assessment: A critical analysis of protection goals, species sensitivity and antimicrobial resistance [J]. Environment International, 2017, 109: 155-169

[2] 李鹏, 谭璐, 李林云, 等. 机舱空气环境耐药基因及耐药细菌的污染特征研究[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2019, 14(3): 130-138

Li P, Tan L, Li L Y, et al. Characteristics of antibiotic resistant genes and resistant bacteria in the air environment of cabin [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2019, 14(3): 130-138 (in Chinese)

[3] Zhang K, Xin R, Zhao Z, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water of China: Occurrence, distribution and influencing factors [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2020, 188: 109837

[4] Ahmed W, Zhang Q, Lobos A, et al. Precipitation influences pathogenic bacteria and antibiotic resistance gene abundance in storm drain outfalls in coastal sub-tropical waters [J]. Environment International, 2018, 116: 308-318

[5] 段宇婧, 吴新颜, 陈则友, 等. 人体肠道耐药基因组的研究进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2020, 15(4): 1-10

Duan Y J, Wu X Y, Chen Z Y, et al. Advances in human gut resistome [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2020, 15(4): 1-10 (in Chinese)

[6] Zhao X H, Lin C W, Wang J, et al. Advances in rapid detection methods for foodborne pathogens [J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2014, 24(3): 297-312

[7] Berg G, Erlacher A, Smalla K, et al. Vegetable microbiomes: Is there a connection among opportunistic infections, human health and our gut feeling? [J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2014, 7(6): 487-495

[8] European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2016 [J]. EFSA Journal European Food Safety Authority, 2017, 15(12): e05077

[9] Liao X Y, Ma Y N, Daliri E B M, et al. Interplay of antibiotic resistance and food-associated stress tolerance in foodborne pathogens [J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2020, 95: 97-106

[10] Liu C, Huang H, Zhou Q, et al. Antibacterial and antibiotic synergistic activities of the extract from Pithecellobium clypearia against clinically important multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria [J]. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 2019, 32: 100999

[11] Kim N H, Yun A R, Rhee M S. Prevalence and classification of toxigenic Staphylococcus aureus isolated from refrigerated ready-to-eat foods (Sushi, Kimbab and California rolls) in Korea [J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2011, 111(6): 1456-1464

[12] Turnbaugh P J, Ley R E, Mahowald M A, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest [J]. Nature, 2006, 444(7122): 1027-1031

[13] Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes [J]. Nature, 2012, 490(7418): 55-60

[14] Knip M, Siljander H. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes mellitus [J]. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2016, 12(3): 154-167

[15] Zhang X, Zhang D, Jia H, et al. The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment [J]. Nature Medicine, 2015, 21(7): 895-905

[16] Rooks M G, Garrett W S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity [J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2016, 16(6): 341-352

[17] Oliver S P, Jayarao B M, Almeida R A. Foodborne pathogens in milk and the dairy farm environment: Food safety and public health implications [J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2005, 2(2): 115-129

[18] Law J W F, Letchumanan V, Chan K G, et al. Insights into Detection and Identification of Foodborne Pathogens [M]//Foodborne Pathogens and Antibiotic Resistance. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017: 153-201

[19] Berger C N, Sodha S V, Shaw R K, et al. Fresh fruit and vegetables as vehicles for the transmission of human pathogens [J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 12(9): 2385-2397

[20] Karch H, Denamur E, Dobrindt U, et al. The enemy within us: Lessons from the 2011 European Escherichia coli O104: H4 outbreak [J]. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 2012, 4(9): 841-848

[21] Brandl M T. Fitness of human enteric pathogens on plants and implications for food safety [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2006, 44: 367-392

[22] Maurice Bilung L, Sin Chai L, Tahar A S, et al. Prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and antibiotic resistance profile of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes at farm level: A highlight of ERIC- and BOX-PCR to reveal genetic diversity [J]. BioMed Research International, 2018, 2018: 3067494

[23] Cerqueira F, Matamoros V, Bayona J, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes distribution in microbiomes from the soil-plant-fruit continuum in commercial Lycopersicon esculentum fields under different agricultural practices [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 652: 660-670

[24] He L Y, Ying G G, Liu Y S, et al. Discharge of swine wastes risks water quality and food safety: Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes from swine sources to the receiving environments [J]. Environment International, 2016, 92-93: 210-219

[25] Cerqueira F, Matamoros V, Bayona J, et al. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in soils and crops. A field study in legume plants (Vicia faba L.) grown under different watering regimes [J]. Environmental Research, 2019, 170: 16-25

[26] Korir R C, Parveen S, Hashem F, et al. Microbiological quality of fresh produce obtained from retail stores on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, United States of America [J]. Food Microbiology, 2016, 56: 29-34

[27] Zhao Y H, Wang Q, Chen Z Y, et al. Significant higher airborne antibiotic resistance genes and the associated inhalation risk in the indoor than the outdoor [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 268: 115620

[28] Rodloff A, Bauer T, Ewig S, et al. Susceptible, intermediate, and resistant: The intensity of antibiotic action [J]. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 2008, 105(39): 657-662

[29] Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock R E W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances [J]. Nature Protocols, 2008, 3(2): 163-175

[30] Bretonnière C, Maitte A, Caillon J, et al. MIC score, a new tool to compare bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics application to the comparison of susceptibility to different penems of clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [J]. The Journal of Antibiotics, 2016, 69(11): 806-810

[31] Bonos E, Giannenas I, Sidiropoulou E, et al. Effect of Bacillus pumilus supplementation on performance, intestinal morphology, gut microflora and meat quality of broilers fed different energy concentrations [J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2021, 274: 114859

[32] Abd-El-Kareem F, Elshahawy I E, Abd-Elgawad M M M. Application of Bacillus pumilus isolates for management of black rot disease in strawberry [J]. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 2021, 31: 25

[33] Punja Z K, Tirajoh A, Collyer D, et al. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis strain QST 713 (Rhapsody) against four major diseases of greenhouse cucumbers [J]. Crop Protection, 2019, 124: 104845

[34] Zhao Y Y, Bi J F, Yi J Y, et al. Dose-dependent effects of apple pectin on alleviating high fat-induced obesity modulated by gut microbiota and SCFAs [J]. Food Science and Human Wellness, 2022, 11(1): 143-154

[35] Loncarevic S, Johannessen G S, Rørvik L M. Bacteriological quality of organically grown leaf lettuce in Norway [J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2005, 41(2): 186-189

[36] Yu K, Newman M C, Archbold D D, et al. Survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on strawberry fruit and reduction of the pathogen population by chemical agents [J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2001, 64(9): 1334-1340

[37] Krumperman P H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1983, 46(1): 165-170

[38] 蒲承君, 吕明环, 曾钰涵, 等. 鸡、猪粪便源大肠杆菌对4种抗生素耐药性的比较[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2017, 12(1): 141-147

Pu C J, Lv M H, Zeng Y H, et al. Drug resistance to four antibiotics of Escherichia coli in chicken and pig feces [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2017, 12(1): 141-147 (in Chinese)

[39] MacDonald K L. The emergence of Escherichia coli O157: H7 infection in the United States [J]. JAMA, 1993, 269(17): 2264

[40] Cooley M, Carychao D, Crawford-Miksza L, et al. Incidence and tracking of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in a major produce production region in California [J]. PLoS One, 2007, 2(11): e1159

[41] Reddy S P, Wang H, Adams J K, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Salmonella serotypes isolated from fresh produce marketed in the United States [J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2016, 79(1): 6-16

[42] Chua P T C, Dykes G A. Attachment of foodborne pathogens to banana (Musa sp.) leaves [J]. Food Control, 2013, 32(2): 549-551

[43] Yanagida T, Shimizu N, Kimura T. Extraction of wax and functional compounds from fresh and dry banana leaves [J]. Japan Journal of Food Engineering, 2005, 6(1): 79-87

[44] Talley J L, Wayadande A C, Wasala L P, et al. Association of Escherichia coli O157: H7 with filth flies (Muscidae and Calliphoridae) captured in leafy greens fields and experimental transmission of E. coli O157: H7 to spinach leaves by house flies (Diptera: Muscidae) [J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2009, 72(7): 1547-1552

[45] Pepper I L, Brooks J P, Gerba C P. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in municipal wastes: Is there reason for concern? [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(7): 3949-3959

[46] Li D L, Zhang H C, Chang F Q, et al. Distribution and health-ecological risk assessment of heavy metals: An endemic disease case study in southwestern China [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2022, 29(3): 4260-4275

[47] 迟荪琳, 王卫中, 徐卫红, 等. 四环素类抗生素对不同蔬菜生长的影响及其富集转运特征[J]. 环境科学, 2018, 39(2): 935-943

Chi S L, Wang W Z, Xu W H, et al. Effects of tetracycline antibiotics on growth and characteristics of enrichment and transformation in two vegetables [J]. Environmental Science, 2018, 39(2): 935-943 (in Chinese)

[48] 邵振鲁, 李厚禹, 李晓晨, 等. 农村固体废弃物中抗生素及耐药基因的赋存及风险管理[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2020, 15(4): 112-122

Shao Z L, Li H Y, Li X C, et al. The occurrence and risk management of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant genes in rural solid waste [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2020, 15(4): 112-122 (in Chinese)

[49] Sazykin I S, Khmelevtsova L E, Seliverstova E Y, et al. Effect of antibiotics used in animal husbandry on the distribution of bacterial drug resistance (review) [J]. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 2021, 57(1): 20-30

[50] Lee K, Kim D W, Lee D H, et al. Mobile resistome of human gut and pathogen drives anthropogenic bloom of antibiotic resistance [J]. Microbiome, 2020, 8(1): 2