塑料是一种通过加聚或缩聚反应聚合而成的高分子化合物,因其材料特性及生产成本低等特点,广泛应用于现代社会生产活动及人们生活中。据统计,全球的塑料产量从20世纪50年代500万t增长到现在3.5亿t以上[1]。每年无法妥善处理的塑料垃圾达882万m3[2]。此外,因新型冠状病毒传染病疫情的世界大流行,全球医用塑料市场预计将从2020年251亿美元增长到2021年294亿美元,因应对新冠疫情所产生的塑料垃圾正在对水道、土壤和空气构成不容忽视的不良影响[3]。据报道,即使人们现在开始采取措施控制塑料垃圾,到2040年全球仍会产生高达7.1亿t的塑料垃圾[4]。大量废弃塑料在水解、光降解、机械磨损以及生物降解等外力作用下,可形成细小的塑料微粒,其中粒径<5 mm的塑料微粒被定义为微塑料(microplastics, MPs)[5],<0.1 μm的微塑料也被称为纳米塑料(nanoplastics, NPs)[6]。由于塑料难以完全降解,能够在环境中持久存在,从而引发严重的环境污染问题。研究人员已在食品、土壤、水体、深海沉积物以及大气等环境介质中发现不同组分和含量的微塑料[7]。同时,在多种生物体内也发现微塑料的存在,特别是水生生物,如浮游动植物、蚌类、虾类、鱼类和海洋哺乳动物等[8-9]。此外,在人体肺组织[10]、人体粪便[11]、人体胎盘[12-13]以及人体结肠样本[14]等人体生物样本中同样检出了微塑料。目前关于微塑料的研究更多集中在海洋、土壤及淡水等生态圈,关于空气微塑料的研究相对较少,近年来陆续有研究报道了部分城市/地区大气环境中微塑料的丰度、尺寸大小、组分类型、形状及颜色等分布特征,如中国上海[15]、中国沿海城市[16]、英国赫尔市和亨伯地区[17]等。本文主要通过文献调研,对当前空气微塑料的来源、分布特征、吸入暴露评估及其毒性效应最新研究进展进行综述及思考,为后续空气微塑料的研究提供科学线索和参考。

1 空气中微塑料的来源(Sources of airborne microplastics)

微塑料按其来源可分为初生微塑料和次生微塑料,初生微塑料指塑料直接以小颗粒的形式进入环境,如化妆品、肥料和油漆涂料等含有的塑料微珠以及合成纤维衣服在生产使用过程中脱落的塑料纤维;次生微塑料指人类活动中产生的较大块塑料进入环境后,经过太阳的紫外线辐射、风化以及其他外力等一系列物理、化学和生物过程导致大块塑料破裂成碎片并降解形成更小的塑料颗粒后形成微小塑料颗粒[18-19]。包装材料等塑料制品及纺织物品在生产、加工以及使用过程中均可产生大量塑料微粒直接或间接进入大气环境中[7]。此外,垃圾填埋场[20]、轮胎磨损[21]和道路扬尘[22]都是室外空气中微塑料的重要来源,研究显示,由轮胎磨损产生的微塑料对全球海洋塑料总量的相对贡献率约为5%~10%,对空气中可吸入颗粒物的贡献率为3%~7%[21]。O’Brien等[22]的研究显示,微塑料浓度与交通负荷量有显著关系(r2=0.63),交通与环境中微塑料的丰度增加有关。除了轮胎的磨损,汽车排放的烟雾也是城市地区室外空气中微塑料的来源之一[23]。另一方面,衣物服饰、家用纺织物品及室内装潢等则可能是室内空气微塑料的重要来源[24],研究显示,一条湿质量为6.5 kg的聚酯纤维(涤纶)毯子在一次机洗干燥中会产生62~874个聚酯纤维(PET纤维)进入空气中[25]。此外,自2019年底新冠疫情暴发以来,口罩已成为当前全球社会人们日常生活中不可或缺的一部分,据报道,全球每天要消耗数10亿个一次性口罩,研究显示,每个外科口罩或N95口罩或能释放超过10亿颗微塑料,这些塑料微粒大小约在5 nm~600 μm之间[26]。因此,口罩也成为了公众日常生活中密切接触的微塑料来源之一。

2 空气微塑料的分布特征及人体暴露评估(Distribution characteristics of airborne microplastics and evaluation of human exposure)

2.1 空气中微塑料的分布特征

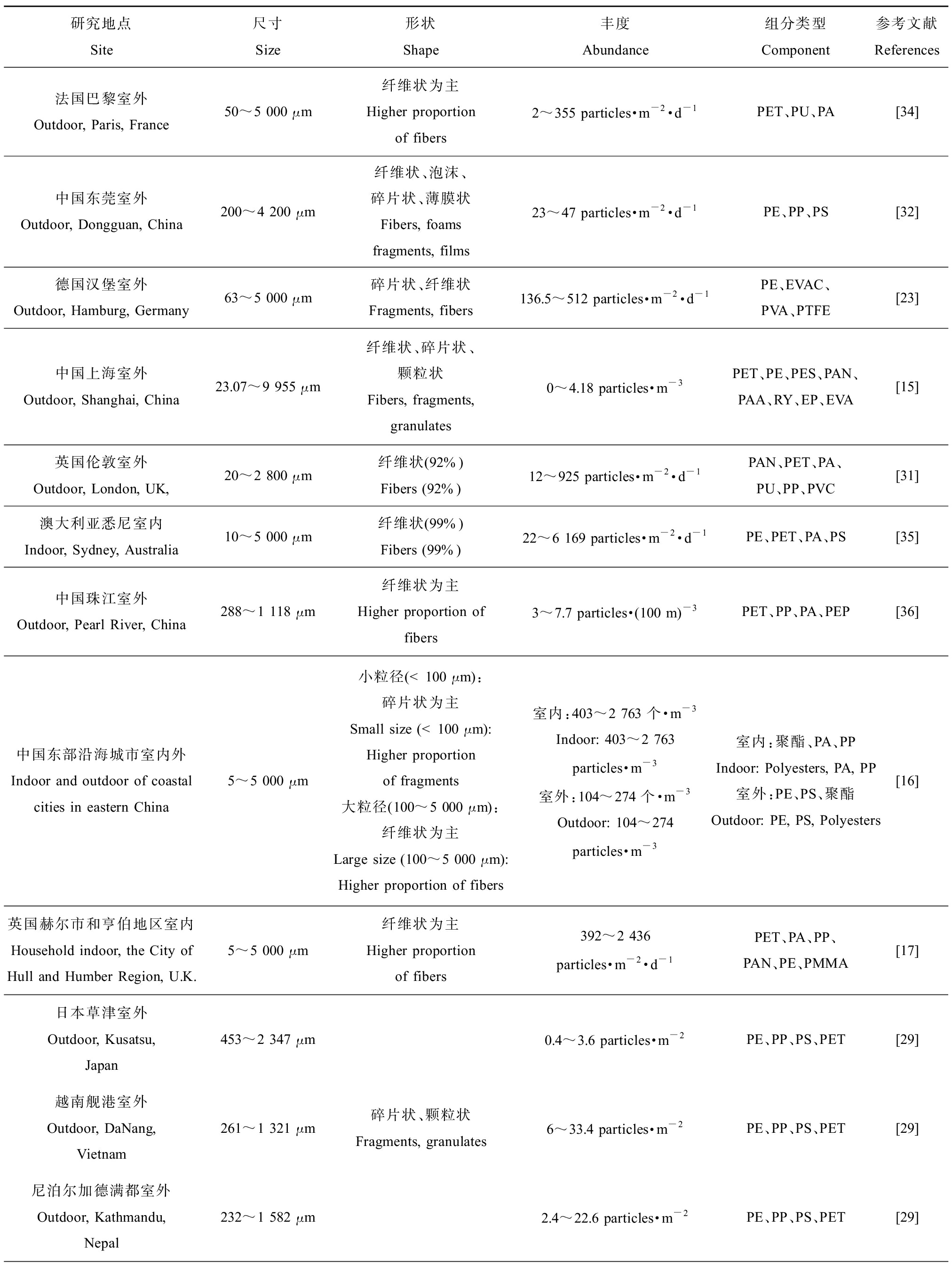

目前空气微塑料的研究大多集中于通过检测所研究区域室内外空气降尘(被动采样)、大气悬浮物或其他动力采样空气样品(主动采样)中的微塑料,分析所研究区域内空气微塑料的分布特征,包括微塑料的丰度、粒径分布、塑料类型、形状及颜色等,空气微塑料的研究报道结果如表1所示,不同国家或地区空气微塑料的丰度差异较大,在Zhang等[27]的一项关于中国、巴基斯坦、希腊、韩国、日本和美国等12个国家室内灰尘微塑料的研究中,聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯(polyethylene terephthalate, PET)在所有样本中均大量检出(29~120 00 μg·g-1),其中PET检出量最高的是韩国(均值25 000 μg·g-1)和日本(均值23 000 μg·g-1),其后是沙特阿拉伯(均值13 000 μg·g-1),其余国家的样本中PET检出量均值均在10 000 μg·g-1以下。近期一项关于中国5座特大城市空气微塑料的研究显示,中国北方城市空气中微塑料的丰度(226~490 个·m-3)高于中国东南部城市(136~324 个·m-3),空气样品中94.7%的微塑料粒径<100 μm,且88.2%的微塑料为碎片状,其中聚乙烯(polyethene, PE)、聚酯纤维(polyester, PET纤维/涤纶)以及聚苯乙烯(polystyrene, PS)为主要检出的塑料类型[28]。此外,道路扬尘作为室外空气中微塑料的来源之一,道路灰尘中微塑料的污染特征影响着空气中微塑料的分布特征,研究显示,日本草津道路灰尘中微塑料(100 μm~5 mm)的丰度最低,为0.4~3.6 个·m-2,而越南舰港和尼泊尔加德满都均远高于日本,分别为6.0~33.4 个·m-2 (14种聚合物类型)、2.4~22.6 个·m-2 (15种聚合物类型),研究者认为道路灰尘中微塑料的污染特征可能与各地区所采取的垃圾处理措施有关[29]。

表1 空气中微塑料的分布特征

Table 1 Distribution characteristics of airborne microplastics

研究地点Site尺寸Size形状Shape丰度Abundance组分类型Component参考文献References法国巴黎室外Outdoor, Paris, France50~5 000 μm纤维状为主Higher proportion of fibers2~355 particles·m-2·d-1PET、PU、PA[34]中国东莞室外Outdoor, Dongguan, China200~4 200 μm纤维状、泡沫、碎片状、薄膜状Fibers, foams fragments, films23~47 particles·m-2·d-1PE、PP、PS[32]德国汉堡室外Outdoor, Hamburg, Germany63~5 000 μm碎片状、纤维状Fragments, fibers136.5~512 particles·m-2·d-1PE、EVAC、PVA、PTFE [23]中国上海室外Outdoor, Shanghai, China23.07~9 955 μm纤维状、碎片状、颗粒状Fibers, fragments, granulates0~4.18 particles·m-3PET、PE、PES、PAN、PAA、RY、EP、EVA[15]英国伦敦室外Outdoor, London, UK,20~2 800 μm纤维状(92%)Fibers (92%)12~925 particles·m-2·d-1PAN、PET、PA、PU、PP、PVC[31]澳大利亚悉尼室内Indoor, Sydney, Australia10~5 000 μm纤维状(99%)Fibers (99%)22~6 169 particles·m-2·d-1PE、PET、PA、PS[35]中国珠江室外Outdoor, Pearl River, China288~1 118 μm纤维状为主Higher proportion of fibers3~7.7 particles·(100 m)-3PET、PP、PA、PEP[36]中国东部沿海城市室内外Indoor and outdoor of coastal cities in eastern China5~5 000 μm小粒径(<100 μm):碎片状为主Small size (<100 μm): Higher proportion of fragments大粒径(100~5 000 μm):纤维状为主Large size (100~5 000 μm): Higher proportion of fibers室内:403~2 763 个·m-3Indoor: 403~2 763 particles·m-3室外:104~274 个·m-3Outdoor: 104~274 particles·m-3室内:聚酯、PA、PPIndoor: Polyesters, PA, PP室外:PE、PS、聚酯Outdoor: PE, PS, Polyesters[16]英国赫尔市和亨伯地区室内Household indoor, the City of Hull and Humber Region, U.K.5~5 000 μm纤维状为主Higher proportion of fibers392~2 436 particles·m-2·d-1PET、PA、PP、PAN、PE、PMMA[17]日本草津室外Outdoor, Kusatsu, Japan 453~2 347 μm越南舰港室外Outdoor, DaNang, Vietnam261~1 321 μm尼泊尔加德满都室外Outdoor, Kathmandu, Nepal232~1 582 μm碎片状、颗粒状Fragments, granulates0.4~3.6 particles·m-2PE、PP、PS、PET[29]6~33.4 particles·m-2PE、PP、PS、PET[29]2.4~22.6 particles·m-2PE、PP、PS、PET[29]

续表1研究地点Site尺寸Size形状Shape丰度Abundance组分类型Component参考文献References澳大利亚昆士兰东南部室外Outdoor in Southeast Queensland, Australia100~1 000 μm-0.5 mg·g-1(农村)~6 mg·g-1(布里斯班市)0.5 mg·g-1(Rural site)~6 mg·g-1(Brisbane city)PVC、PET、PE、PP、PS、PMMA[22]中国39个城市室内外Indoor and outdoor in 39 cities in China50~5 000 μm纤维状为主Higher proportion of fibers室内PET: 1 550~120 000 mg·kg-1Indoor PET: 1 550~120 000 mg·kg-1室外PET: 212~9 020 mg·kg-1Outdoor PET: 212~9 020 mg·kg-1室内PC: 4.6 mg·kg-1Indoor PC: 4.6 mg·kg-1室外PC: 2.0 mg·kg-1Outdoor PC: 2.0 mg·kg-1PET、PC[24]美国加州沿海城市室内外Indoor and outdoor in coastal cities of California, USA室内:58.6~641 μmIndoor: 58.6~641 μm室外:104.8~616 μmOutdoor: 104.8~616 μm纤维状、碎片状Fibers, fragments室内: 15.9 个·m-3Indoor: 15.9 particles·m-3室外: 7.2 个·m-3Outdoor: 7.2 particles·m-3PS、PET、PE、PVC、PC、PA、ABS[30]中国5座特大城市Five megacities of China94.7% <100 μm碎片状(88.2%)Fragments (88.2%)北方城市: 226~490 个·m-3Northern cities: 226~490 particles·m-3东南部城市: 136~324 个·m-3Southeast cities: 136~324 particles·m-3PE、聚酯(Polyesters)、PS[28]中国环渤海沿海城市室外Outdoor, coastal cities around the Bohai Sea, China<1 mm纤维状(>90%)、薄膜状、碎片状、颗粒状Fibers (>90%), films, fragments, granulates烟台:35.7~154.4 个·m-2·d-1Yantai: 35.7~154.4 particles·m-2·d-1天津: 119.0~327.1 个·m-2·d-1Tianjin: 119.0~327.1 particles·m-2·d-1大连: 98.4~391.4 个·m-2·d-1Dalian: 98.4~391.4 particles·m-2·d-1赛璐玢(Cellophane) (>50%)、PET (>30%)[37]中国大连海岸带室外Outdoor, Dalian coastal zone, China<1 mm纤维状为主Higher proportion offibers-PET、赛璐玢(Cellophane)、EPD[38]

注:PP表示聚丙烯;PET表示聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯;PC表示聚碳酸酯;PE表示聚乙烯;PA表示聚酰胺/尼龙;PVC表示聚氯乙烯;PS表示聚苯乙烯;ABS表示丙烯腈-丁二烯-苯乙烯;PAA表示聚丙烯酸;PU表示聚氨酯;PMMA表示聚甲基丙烯酸甲酯;RY表示人造丝;PAN表示聚丙烯腈;PES表示聚醚砜树脂;PTFE表示聚四氟乙烯;PVA表示聚乙烯醇;EPD表示乙烯-丙烯-二烯三元共聚物;EVAC表示乙烯-乙酸乙烯酯树脂;EVA表示乙烯-醋酸乙烯共聚物;EP表示环氧树脂;PEP表示乙烯丙烯共聚物。

Note: PP represents polypropylene; PET represents polyethylene terephthalate; PC represents polycarbonate; PE represents polyethene; PA represents polyamide and nylon; PVC represents polyvinyl chloride; PS represents polystyrene; ABS represents acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic; PAA represents polyacrylic acid; PU represents polyurethane; PMMA represents polymethylmethacrylate; RY represents rayon; PAN represents polyacrylonitrile; PES represents poly(ether sulfones); PTFE represents polytetra fluoroethylene; PVA represents polyvinylalcohol; EPD represents ethylene-propylene-diene; EVAC represents ethylene-vinyl acetate resin; EVA represents ethylvinyl acetate copolymer; EP represents epoxy resin; PEP represents poly(ethylene-co-propylene).

城市地区与乡村地区在交通负荷、工业化程度以及人口密度等方面存在明显差异,而各地区工业化水平、城市交通以及道路扬尘影响着空气中微塑料的分布特征。根据O’Brien等[22]对澳大利亚道路降尘微塑料的研究显示,在丰度方面,城市地区道路降尘中微塑料的丰度(2.8~9.0 mg·g-1)明显高于乡村地区(0.37~0.69 mg·g-1);在粒径分布方面,交通负荷大的道路降尘中小粒径微塑料较乡村地区多,而乡村地区道路降尘中大粒径微塑料较多。在一项关于中国东部沿海城市和乡村地区空气中微塑料的研究中,城市空气中微塑料丰度(154~294 个·m-3)明显高于农村地区空气中微塑料(54~148 个·m-3),但在粒径分布方面,小粒径微塑料(5~30 μm)在乡村地区空气中更高,较大粒径微塑料(300~3 000 μm)在城市地区空气中较乡村地区高[16]。乡村地区由于人口密度低,交通量负荷小,人为活动造成的道路扬尘较少,空气中大粒径微塑料自然沉降之后导致地面灰尘中大颗粒的微塑料较多,而小粒径微塑料可在空气中停留更久,因此小粒径微塑料在乡村地区空气中的丰度更高。此外,研究人员认为城市地区的街道清扫可能影响着空气中微塑料的粒径分布[22],由于城市交通负荷大,人口密度大以及道路清扫频繁,与农村地区相比,城市地区人类活动造成的道路扬尘使较大粒径微塑料更有机会再次漂浮在空气中。

除了城乡差异,空气中微塑料的分布特征也存在室内外差异。在丰度方面,研究显示室内空气中微塑料的丰度明显高于室外空气环境中微塑料的丰度,在Liao等[16]的研究中,室内空气中微塑料的丰度比室外高10倍。同样在Gaston等[30]的研究中也显示,室内微塑料的丰度明显高于室外。在粒径分布方面,研究显示,在同一地区室内和室外空气中微塑料的粒径分布没有明显差异[16]。由于现阶段微塑料检查分析方法和仪器分析能力的限制,目前大多数研究所报道的微塑料粒径大小基本在1~5 000 μm之间,其中空气中小粒径微塑料占比高于大粒径微塑料,且随着粒径增大而减少[31]。在Jenner等[17]的研究中,小粒径微塑料(5~250 μm)占比达59%,而在Liao等[16]的研究中,空气中<30 μm的微塑料>60%,30~100 μm的微塑料在30%左右,而300~1 000 μm的微塑料和1 000~5 000 μm的微塑料仅占2.2%和0.5%。在形状方面,纤维状、碎片状以及颗粒状微塑料普遍检出,在英国伦敦地区空气中纤维状微塑料占比高达92%[31],在英国赫尔市和亨伯地区室内空气中纤维状微塑料占比90%,碎片状微塑料占比8%,其余为薄膜状和球形,分别占比1%[17]。在Liu等[24]的研究中,室内和室外灰尘中均显示纤维状微塑料检出量占比最大,其次颗粒状微塑料,且室内纤维状微塑料的占比(88.0%)高于室外(73.7%)。同样在中国上海地区大气悬浮微塑料中,纤维状微塑料达67%,其次是碎片状微塑料(30%)和颗粒状微塑料(3%)[15]。空气中微塑料的形状分布特征可能与微塑料的粒径大小有关,在Loppi等[20]的研究中,碎片状微塑料的平均大小为45~66 μm之间,纤维状微塑料的平均长度在550~796 μm之间。在Liao等[16]的研究中,不管室内还是室外,小粒径(5~100 μm)微塑料中碎片状微塑料占比更多,与Zhu等[28]的研究结果一致,且粒径越小碎片状微塑料占比越高,粒径在5~30 μm的微塑料中碎片状微塑料占比高达90%以上,而在粒径300~5 000 μm的微塑料中,则是纤维状占比较多,研究者认为,与小粒径碎片状微塑料相比,大的纤维状微塑料可能更容易被观察到和被检测到,因此也被报道得更多。组分特征方面,在室内空气微塑料中,聚酯(PET纤维/涤纶)、聚酰胺(PA)以及聚丙烯(PP)普遍被检出。在Liao等[16]的研究中,在室内空气的微塑料中PET纤维占比28.4%、PA占比20.54%,PP占比16.3%。同样在Jenner等[17]的研究中,PET是所有室内样品中检出量最多的微塑料类型(63%),其次是PA、PP等。Zhang等[27]的研究显示,PET在所研究的12个国家室内灰尘中均大量检出,其中作为PET最大生产国,中国室内灰尘样品中PET检出量最高,研究者认为经济发展水平和人类活动均影响着室内微塑料的分布特征,PET作为纺织品和包装行业的主要材料,在全球范围内大量生产和使用,导致空气污染物中PET普遍存在。相较于室内,室外空气中微塑料的组分更加复杂多样。在中国上海的大气悬浮微塑料中,PET、聚乙烯(PE)以及PET纤维/涤纶共占比49%,此外,聚丙烯腈(PAN)、聚丙烯酸(PAA)和人造丝(RY)等均有检出[15]。在意大利垃圾填埋场周围地衣上积累的微塑料中检出最多的也是聚酯和PET[20]。在中国东莞的大气沉降物中除了PE外,还发现大量PP和PS[32]。此外,在英国伦敦中心城区,研究者发现PAN是空气微塑料中含量最多的塑料类型(67%),且聚酯(PET纤维/涤纶)、聚酰胺(尼龙)、聚氨酯(PU/PUR)、PE、PP、聚氯乙烯(PVC)和PS等均被检出,研究者认为,室外大气中微塑料的分布特征与其来源有关,工业排放、废弃塑料垃圾的碎裂和服饰衣物等纺织物品的户外晾晒,轮胎磨损以及汽车尾气排放等均影响着室外空气中微塑料的分布特征[31]。目前为止,用于表征空气中微塑料含量的丰度单位尚没有统一方式或标准方法,现有文献资料中对于表征空气中微塑料含量的丰度单位主要有5种:个·m-2·d-1、个·m-3、个·m-2、个·g-1和mg·kg-1,其中采用个·m-2·d-1和体积单位表征空气中微塑料丰度的较多[33]。

2.2 空气微塑料的暴露评估研究现状

自1998年,Pauly等[39]的研究在人体肺组织压片中发现塑料纤维,越来越多研究者关注及研究空气中微塑料的人体暴露量及其在机体内沉积可能引起的健康风险。空气-呼吸系统、食物/饮水-消化系统以及洗漱/护肤产品-皮肤是人体日常生活中较常见的3种微塑料暴露途径[40],其中经呼吸系统的吸入途径被认为更为普遍[6],据报道,通过呼吸道途径吸入微塑料的量是消化道途径摄入微塑料的3倍~15倍[5]。目前大部分研究主要通过测量海洋生物、空气样品、食品及家庭用品等环境介质中微塑料的量来评估人体微塑料的外暴露水平。例如,研究显示,人体通过室内尘埃吸入PET和聚碳酸酯(PC)的量分别为360~150 000 ng·kg-1·d-1和0.88~270 ng·kg-1·d-1,且婴儿的吸入量暴露高于成人[27]。Liu等[24]的研究同样表明,由于婴幼儿体质量较轻,室内暴露时间较长,吸尘率较高,婴幼儿的微塑料暴露值最高,而儿童每天摄入PET微塑料为17 300 ng·kg-1。此外,研究显示,人体在室内环境中吸入的微塑料颗粒比在室外高1倍~45倍[17]。Vianello等[41]利用热呼吸人体模型模拟人体呼吸的研究显示,人体在室内24 h内吸入微塑料总数达到272个颗粒,平均量达到(9.3±5.8) 个·m-3。近期一项研究显示,在人体鼻腔冲洗液和痰液中均观察到疑似微塑料污染物的存在,平均丰度分别为0.8 个·g-1和105.4 个·g-1,平均长度分别为590.3 μm和505.6 μm,且90%为纤维状[42],与当前国内外大部分研究报道空气中大粒径微塑料的形态分布相一致。在最新一项人体肺组织微塑料的研究中,研究人员通过对20份人体肺部组织样本进行微塑料检测,发现在13份人体肺部组织中检出37个微塑料颗粒,每克人体肺组织中大概含有0.56个微塑料,以PP和PE以及棉织物等为主要组分,碎片状微塑料粒径均<5.5 μm,纤维状微塑料长度在8.12~16.8 μm之间,且所检出的微塑料中,87.5%为碎片状,12.5%为纤维状,该研究中微塑料的形态分布与前文所提及的小粒径微塑料的形状分布特征相一致[10]。研究者认为,空气中纤维微塑料能否进入呼吸系统主要取决于尺寸和密度,其中长度直径比超过3的纤维状微塑料,虽可被人体吸入,但可能受到上呼吸道黏液纤毛清除机制的影响,从而被清除出体外或转变成胃肠道暴露[40, 43]。一项关于颗粒物在人体肺部沉积规律及影响因素的研究显示,粒径在6~10 μm之间的颗粒物主要沉积在气管及支气管前端,粒径在0.5~6 μm之间的颗粒物主要沉积在肺泡区,粒径<0.5 μm的颗粒物可沉积在细支气管以及肺泡深处[44]。但由于目前检测方法以及检测仪器的检测能力的限制,许多1 μm以下的微塑料及纳米塑料未能被检出及表征。

3 微塑料的吸入毒性效应(The inhalation toxic effect of microplastics)

3.1 微塑料的吸入沉积及其对呼吸系统的毒性效应

人体吸入微塑料后,微塑料进入气道并根据颗粒特性、人体特异性和呼吸道结构特征到达不同部位[6],其中较大颗粒(>10 μm)一般沉积在口径较大的上呼吸道,较小的颗粒在较小的气道(肺外周区)沉积,且随着颗粒尺寸减小,其穿透指数值显著增加[45]。据报道,5~30 μm的颗粒因鼻咽壁的撞击而更多沉积在上呼吸道,密度较低的小颗粒(如PE)则可能到达深部气道,1~5 μm的颗粒可通过沉降和扩散到达小气道,而<1 μm的颗粒沉积则通过布朗运动可到达更深处[6, 45]。沉积后,部分微塑料颗粒可通过多种机制被清除,如纤毛黏液运动、肺泡巨噬细胞吞噬或通过淋巴系统迁移[6, 46]。研究发现,当吸入的颗粒超过清除机制的负荷时,颗粒物沉积增多,当肺颗粒体积负荷超过肺巨噬细胞体积的6%时,就会发生慢性炎症,同时,一旦达到这个剂量阈值,肺泡巨噬细胞的流动性和它们清除肺泡表面颗粒的能力将会减弱[47]。人体内沉积的微塑料对人体的健康效应可能与微塑料的化学性质、结构特性、添加剂、人体特异性以及微塑料表面吸附及携带的有毒有害物质有关[6]。研究发现,细胞与颗粒/纤维之间的相互作用引起炎症后又会由于氧化应激的持续产生而诱导细胞增殖和继发性遗传毒性,且小粒径颗粒(如纳米塑料)更容易通过扩散机制沿呼吸道到达肺泡,进入细胞并诱导细胞毒性效应[48-49]。研究显示,暴露于聚苯乙烯微塑料可导致人体肺细胞增殖抑制和细胞形态发生变化[50]。Dong等[51]的研究显示,吸入高浓度PS-MPs可通过诱导活性氧形成而引起肺上皮细胞的细胞毒性和炎症反应,增加慢性阻塞性肺疾病的患病风险,即使吸入低浓度PS-MPs也会破坏人体保护性肺屏障,增加肺部疾病的患病风险。此外,研究发现,聚苯乙烯纳米颗粒(PS-NPs)在肺上皮细胞和巨噬细胞中具有潜在毒性,可诱导自噬细胞死亡[52]。Paget等[53]的研究显示,PS-NPs对人体肺上皮细胞存在潜在细胞毒性和遗传毒性效应,且与纳米塑料颗粒的表面化学特性有关。Wu等[54]的研究发现,0.1 μm和5 μm 2种粒径大小的PS-MPs对细胞活力、氧化应激、膜完整性和流动性均表现出低毒性效应,且其毒性效应可能与其粒径大小有关。Xu等[55]研究了2种不同尺寸(25 nm和70 nm) PS-NPs对人肺泡上皮细胞的内化、细胞活力、细胞周期、凋亡以及相关基因转录和蛋白表达的影响,结果显示,PS-NPs能够干扰基因表达,导致炎症反应和启动细胞凋亡途径;同时证明,在高浓度下,PS-NPs以剂量依赖性方式抑制细胞活力,而在低浓度时,PS-NPs则以粒径大小依赖性方式影响细胞活力,小粒径PS-NPs(25 nm)比大粒径PS-NPs(70 nm)更快速有效地内化到A549的细胞质中。除了上述在实验室常规微塑料人为暴露的毒性研究发现外,微塑料的吸入毒性效应在实际工业环境领域也有相关研究报道[33],合成纺织业、塑料制造业等行业工人可能会因长期暴露于高丰度微塑料而罹患呼吸道疾病、肺癌、胃癌和食道癌等职业病[56]。在一些职业暴露的工人中发现,长期慢性暴露于空气中某种特定类型的微塑料可导致癌症发病风险增加,例如,职业暴露于PVC粉尘的工人患肺癌风险增加,且与暴露、年龄和工作年限等相关,同时研究表明PVC粉尘可能会造成呼吸道和肺组织物理损伤[57]。在纺织工厂中,纺织工人接触呼吸性粉尘可引起多种不同的呼吸系统健康问题,其中包括慢性阻塞性肺疾病、呼吸刺激等,咳嗽、咳痰和胸闷等[58]。在Song等[59]一项长期慢性吸入PS-NPs的职业暴露研究中,7名年轻女工暴露于PS-NPs中5~13个月,她们在相同的时间范围内均出现相同的病理症状:非特异性肺炎症、炎症浸润、肺纤维化和胸膜异体肉芽肿。同样在近期一项关于纺织厂工人职业性肺病的研究中,因工作场所暴露浓度高,暴露时间长以及个体易感性,部分纺织工人出现呼吸道过敏和一些急性呼吸系统症状(以胸闷、咳嗽、呼吸困难为主)[60]。这些工业环境中空气微塑料的职业暴露研究表明,空气中高浓度微塑料暴露和呼吸道损伤以及肺部病变的发展之间存在联系,提示人体通过呼吸途径日常暴露于空气微塑料中也许存在健康风险。

3.2 微塑料吸入暴露后的易位毒性效应

除了呼吸道损伤和肺部病变外,吸入的小粒径塑料颗粒可通过血液转运到达其他部位并引起其他器官组织的毒性。肺泡表面有一个<1 μm的非常薄的屏障,小粒径塑料颗粒可以穿过呼吸屏障到达血液,特别是在出现炎症时,内皮细胞和上皮细胞通透性增加,小粒径颗粒(如纳米塑料颗粒)可以进入血液,通过循环系统进入肝、肾等其他组织器官继而产生毒性作用[6]。研究证实,小粒径(如纳米塑料颗粒)可穿透肺上皮细胞的细胞膜,并可滞留在细胞质和核质中,也可聚集在红细胞的细胞膜周围并发挥毒性[59]。近期一项研究显示,产妇剖宫产后在胎盘和胎粪中检出聚乙烯、聚丙烯、聚苯乙烯和聚氨酯等10种常见微塑料,再次证实小粒径塑料颗粒可通过体内循环系统易位沉积[61]。Fournier等[62]的研究显示,PS-NPs经气管灌注到怀孕母鼠后,在母体的肺、心脏和脾脏中均检测到PS-NPs,同时发现PS-NPs也转移到了胎儿肝脏、肺、心脏、肾脏和大脑中,并使胎儿和胎盘受到不良影响。已有研究报道,PS-MPs能够扰乱母体-胎儿免疫平衡并对妊娠小鼠产生生殖毒性[63]。大鼠实验显示,PS-MPs可能通过氧化应激触发的NLRP3/Caspase-1信号通路诱导卵巢颗粒细胞的热下垂和凋亡,表明微塑料对卵巢有不良影响,提示微塑料可能对女性生殖系统具有潜在毒性风险[64]。研究显示,高剂量微塑料暴露对男性同样可能存在生殖毒性,Li等[65]的研究表明,高剂量微塑料暴露可通过激活MAPK-Nrf2途径导致血睾屏障(BTB)完整性的破坏和生精细胞的凋亡,精子活力和浓度降低,精子畸形率升高。Kwon等[66]的研究证实,PS-MPs还可在小鼠脑内小胶质细胞中沉积,且小粒径PS-MPs(0.2 μm)比大粒径PS-MPs(10 μm)在小胶质细胞免疫激活中更具有潜在毒性,可导致小鼠和人类大脑的小胶质细胞凋亡。在小鼠实验中观察到,微塑料可导致结肠黏蛋白分泌减少,进而对肠道屏障功能造成损伤,同时微塑料还可引起肠道菌群失调,进而引起胃肠道功能后续一系列病变过程[67]。肝脏作为主要的代谢器官,也是微塑料的主要积蓄器官之一,研究显示,微塑料除了引起肝脏组织学损伤外,还可引起能量和脂质代谢紊乱以及氧化应激[68]。

3.3 空气微塑料潜在的复合毒性

由于微塑料具有高比表面积和疏水性的特性,在环境中经过长期老化作用及吸附作用,微塑料可作为载体吸附及积累环境当中一些有毒有害污染物,如持久性有机污染物(POPs)、重金属和致癌性多环芳烃(PAHs)等,可能存在复合毒性,从而引起健康危害效应[33]。研究显示,在大气颗粒物中检出多种有毒污染物,包括重金属汞(Hg)、PAHs、多氯联苯(PCBs)和有机氯农药(OCPs)等[69],这些有毒有害污染物可吸附在微塑料中并通过被吸食途径进入食物链在生物体内富集,有研究报道,在黑秃鹫体内的微塑料中发现有机氯农药、PAHs、金属和金属类物质[70]。近期一项对PE微塑料和2种PCBs同系物与人类肝癌细胞的毒理学研究显示,微塑料吸附的有机污染物可显著改变其毒性作用,且微塑料与PCBs等亲脂性有机污染物产生的复合毒性比单独微塑料暴露产生的危害更大[71]。Sharma等[72]的研究显示,人体摄入富含致癌性PAHs的微塑料可导致人体罹患癌症的风险增加,微塑料对致癌物PAHs的吸附量可达236 μg·g-1,根据微塑料摄入寿命计算的癌症风险分别为1.13×10-5(儿童)和1.28×10-5(成人),均高于建议值。据报道,不同类型微塑料可对不同重金属重点吸附,且微塑料在环境中吸附重金属后产生的复合毒性比单一暴露产生的危害明显增大[73]。此外,空气微塑料还可成为病毒、致病菌和抗生素耐药基因等有害物质的载体,携带这些有害物质通过呼吸吸入或食物污染等途径进入人体,继而对人体健康产生危害。Cheng等[74]的研究显示,抗生素耐药基因可吸附到微塑料中,并通过微塑料进行传播。研究表明,大连海岸带夏、秋季大气沉降塑料碎片附生生物膜中存在与人类疾病密切相关的功能基因[38]。最新一项研究显示,在空气微塑料的表面发现新型冠状病毒的存在,空气微塑料是新型冠状病毒的一种载体,并增加病毒存活率[75]。为了充分了解空气微塑料复合毒性的潜在危害,需要更多研究聚焦于空气微塑料与其复合污染物之间的相互作用及其相关的致病作用与机理。

4 总结及展望(Summary and prospect)

相较于水体、土壤等生态圈,目前人们对于空气中微塑料的了解与认知仍十分有限,本文主要对空气微塑料的来源、分布特征、暴露评估及微塑料毒性效应的当前研究进展进行综述和思考。由于缺少统一的检测标准和评估方法,相关研究区域内空气微塑料的各研究结果之间无法进行系统比较及综合分析,同时目前尚缺乏空气微塑料的人体内暴露研究及日常暴露的健康风险评估相关研究。为了更全面地了解空气中微(纳米)塑料的污染现状,分析微塑料的吸入暴露特征及评估其健康风险,结合当前空气微塑料的研究现状,展望今后空气微塑料研究:(1)为了快速、准确且全面地分析空气中微塑料的污染特征以及人体暴露特征,需要建立相关样品中微塑料的分离及检测标准化方法,同时提高微塑料检测仪器的分析能力和检测效率,使样品中更多小粒径(<1 μm)微塑料及纳米塑料能够被高效准确地定性定量检测及表征;(2)进一步研究微(纳米)塑料在人体呼吸系统的内暴露特征、沉积规律、易位沉积路径及其吸入毒性机制;(3)深入研究微塑料合并其含有的阻燃剂、增塑剂等化学添加剂以及其表面吸附的有机污染物、重金属等有毒有害物所产生的复合毒性;(4)进一步开展空气微塑料的环境流行病学和职业流行病学研究,综合评估空气微塑料日常暴露的健康风险。

[1] 王菡娟. “塑”尽其用须速办[N]. 人民政协报, 2021-07-22(5)

[2] 陈婉. 塑料污染治理需协同多方力量共同行动[J]. 环境经济, 2020(19): 28-31

[3] Amato-Lourenço L F, Dos Santos Galvão L, de Weger L A, et al. An emerging class of air pollutants: Potential effects of microplastics to respiratory human health? [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 749: 141676

[4] Lau W W Y, Shiran Y, Bailey R M, et al. Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution [J]. Science, 2020, 369(6510): 1455-1461

[5] Pironti C, Ricciardi M, Motta O, et al. Microplastics in the environment: Intake through the food web, human exposure and toxicological effects [J]. Toxics, 2021, 9(9): 224

[6] Facciolà A, Visalli G, Pruiti Ciarello M, et al. Newly emerging airborne pollutants: Current knowledge of health impact of micro and nanoplastics [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(6): 2997

[7] Rhodes C J. Solving the plastic problem: From cradle to grave, to reincarnation [J]. Science Progress, 2019, 102(3): 218-248

[8] Frias J P G L, Otero V, Sobral P. Evidence of microplastics in samples of zooplankton from Portuguese coastal waters [J]. Marine Environmental Research, 2014, 95: 89-95

[9] Bellas J, Martínez-Armental J, Martínez-Cámara A, et al. Ingestion of microplastics by demersal fish from the Spanish Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2016, 109(1): 55-60

[10] Amato-Lourenço L F, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior G R, et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 416: 126124

[11] Schwabl P, Köppel S, Königshofer P, et al. Detection of various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series [J]. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2019, 171(7): 453-457

[12] Ragusa A, Svelato A, Santacroce C, et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta [J]. Environment International, 2021, 146: 106274

[13] Braun T, Ehrlich L, Henrich W, et al. Detection of microplastic in human placenta and meconium in a clinical setting [J]. Pharmaceutics, 2021, 13(7): 921

[14] Ibrahim Y S, Tuan Anuar S, Azmi A A, et al. Detection of microplastics in human colectomy specimens [J]. JGH Open: An Open Access Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2020, 5(1): 116-121

[15] Liu K, Wang X H, Fang T, et al. Source and potential risk assessment of suspended atmospheric microplastics in Shanghai [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 675: 462-471

[16] Liao Z L, Ji X L, Ma Y, et al. Airborne microplastics in indoor and outdoor environments of a coastal city in Eastern China [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 417: 126007

[17] Jenner L C, Sadofsky L R, Danopoulos E, et al. Household indoor microplastics within the Humber region (United Kingdom): Quantification and chemical characterisation of particles present [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2021, 259: 118512

[18] van Wezel A, Caris I, Kools S A E. Release of primary microplastics from consumer products to wastewater in the Netherlands [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2016, 35(7): 1627-1631

[19] Barboza L G A, Gimenez B. Microplastics in the marine environment: Current trends and future perspectives [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2015, 97(1-2): 5-12

[20] Loppi S, Roblin B, Paoli L, et al. Accumulation of airborne microplastics in lichens from a landfill dumping site (Italy) [J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1): 4564

[21] Kole P J, Löhr A J, van Belleghem F, et al. Wear and tear of tyres: A stealthy source of microplastics in the environment [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017, 14(10): 1265

[22] O’Brien S, Okoffo E D, Rauert C, et al. Quantification of selected microplastics in Australian urban road dust [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 416: 125811

[23] Klein M, Fischer E K. Microplastic abundance in atmospheric deposition within the Metropolitan area of Hamburg, Germany [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 685: 96-103

[24] Liu C G, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Widespread distribution of PET and PC microplastics in dust in urban China and their estimated human exposure [J]. Environment International, 2019, 128: 116-124

[25] O’Brien S, Okoffo E D, O’Brien J W, et al. Airborne emissions of microplastic fibres from domestic laundry dryers [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 747: 141175

[26] Ma J, Chen F Y, Xu H, et al. Face masks as a source of nanoplastics and microplastics in the environment: Quantification, characterization, and potential for bioaccumulation [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 288: 117748

[27] Zhang J J, Wang L, Kannan K. Microplastics in house dust from 12 countries and associated human exposure [J]. Environment International, 2020, 134: 105314

[28] Zhu X, Huang W, Fang M Z, et al. Airborne microplastic concentrations in five megacities of northern and southeast China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(19): 12871-12881

[29] Yukioka S, Tanaka S, Nabetani Y, et al. Occurrence and characteristics of microplastics in surface road dust in Kusatsu (Japan), Da Nang (Vietnam), and Kathmandu (Nepal) [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2020, 256: 113447

[30] Gaston E, Woo M, Steele C, et al. Microplastics differ between indoor and outdoor air masses: Insights from multiple microscopy methodologies [J]. Applied Spectroscopy, 2020, 74(9): 1079-1098

[31] Wright S L, Ulke J, Font A, et al. Atmospheric microplastic deposition in an urban environment and an evaluation of transport [J]. Environment International, 2020, 136: 105411

[32] Cai L Q, Wang J D, Peng J P, et al. Characteristic of microplastics in the atmospheric fallout from Dongguan City, China: Preliminary research and first evidence [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2017, 24(32): 24928-24935

[33] 周帅, 李伟轩, 唐振平, 等. 气载微塑料的赋存特征、迁移规律与毒性效应研究进展[J]. 中国环境科学, 2020, 40(11): 5027-5037

Zhou S, Li W X, Tang Z P, et al. Progress on the occurrence, migration and toxicity of airborne microplastics [J]. China Environmental Science, 2020, 40(11): 5027-5037 (in Chinese)

[34] Dris R, Gasperi J, Saad M, et al. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment? [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2016, 104(1-2): 290-293

[35] Soltani N S, Taylor M P, Wilson S P. Quantification and exposure assessment of microplastics in Australian indoor house dust [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 283: 117064

[36] Wang X H, Li C, Liu K, et al. Atmospheric microplastic over the South China Sea and East Indian Ocean: Abundance, distribution and source [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 389: 121846

[37] 田媛, 涂晨, 周倩, 等. 环渤海海岸大气微塑料污染时空分布特征与表面形貌[J]. 环境科学学报, 2020, 40(4): 1401-1409

Tian Y, Tu C, Zhou Q, et al. The temporal and spatial distribution and surface morphology of atmospheric microplastics around the Bohai Sea [J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 2020, 40(4): 1401-1409 (in Chinese)

[38] 涂晨, 田媛, 刘颖, 等. 大连海岸带夏、秋季大气沉降(微)塑料的赋存特征及其表面生物膜特性[J]. 环境科学, 2022, 43(4): 1821-1828

Tu C, Tian Y, Liu Y, et al. Occurrence of atmospheric (micro)plastics and the characteristics of the plastic associated biofilms in the coastal zone of Dalian in summer and autumn [J]. Environmental Science, 2022, 43(4): 1821-1828 (in Chinese)

[39] Pauly J L, Stegmeier S J, Allaart H A, et al. Inhaled cellulosic and plastic fibers found in human lung tissue [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 1998, 7(5): 419-428

[40] 王英雪, 徐熳, 王立新, 等. 微塑料在哺乳动物的暴露途径、毒性效应和毒性机制浅述[J]. 环境化学, 2021, 40(1): 41-54

Wang Y X, Xu M, Wang L X, et al. The exposure routes, organ damage and related mechanism of the microplastics on the mammal [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2021, 40(1): 41-54 (in Chinese)

[41] Vianello A, Jensen R L, Liu L, et al. Simulating human exposure to indoor airborne microplastics using a Breathing Thermal Manikin [J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9: 8670

[42] 那军, 耿译航, 蒋莹, 等. 快递员痰液和鼻腔冲洗液中微塑料污染分析[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2021, 37(3): 451-454

Na J, Geng Y H, Jiang Y, et al. Microplastics detected in sputum and nasal lavage fluid of couriers: A pilot study [J]. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 2021, 37(3): 451-454 (in Chinese)

[43] Gasperi J, Stephanie L W, Rachid D, et al. Microplastics in air: Are we breathing it in? [J]. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 2018, 1: 1-5

[44] 郭西龙. 颗粒物在人体肺部沉积规律及影响因素研究[D]. 长沙: 中南大学, 2013: 22-23

Guo X L. Particle deposition in human lungs: Mechanisms and factors [D]. Changsha: Central South University, 2013: 22-23 (in Chinese)

[45] Carvalho T C, Peters J I, Williams III R O. Influence of particle size on regional lung deposition—What evidence is there? [J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2011, 406(1-2): 1-10

[46] Xu M K, Gulinare H, Qianru Z, et al. Internalization and toxicity: A preliminary study of effects of nanoplastic particles on human lung epithelial cell [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 694: 133794

[47] Pauluhn J. Poorly soluble particulates: Searching for a unifying denominator of nanoparticles and fine particles for DNEL estimation [J]. Toxicology, 2011, 279(1-3): 176-188

[48] H Greim P B. Toxicity of fibers and particles-Report of the workshop held in Munich, Germany, 26-27 October 2000 [J]. Inhalation Toxicology, 2001, 13(9): 737-754

[49] Geiser M, Kreyling W G. Deposition and biokinetics of inhaled nanoparticles [J]. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 2010, 7: 2

[50] Goodman K E, Hare J T, Khamis Z I, et al. Exposure of human lung cells to polystyrene microplastics significantly retards cell proliferation and triggers morphological changes [J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2021, 34(4): 1069-1081

[51] Dong C D, Chen C W, Chen Y C, et al. Polystyrene microplastic particles: In vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 385: 121575

[52] Chiu H W, Xia T, Lee Y H, et al. Cationic polystyrene nanospheres induce autophagic cell death through the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress [J]. Nanoscale, 2015, 7(2): 736-746

[53] Paget V, Dekali S, Kortulewski T, et al. Specific uptake and genotoxicity induced by polystyrene nanobeads with distinct surface chemistry on human lung epithelial cells and macrophages [J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(4): e0123297

[54] Wu B, Wu X, Liu S, et al. Size-dependent effects of polystyrene microplastics on cytotoxicity and efflux pump inhibition in human Caco-2 cells [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 221: 333-341

[55] Xu M K, Halimu G, Zhang Q R, et al. Internalization and toxicity: A preliminary study of effects of nanoplastic particles on human lung epithelial cell [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 694: 133794

[56] Prata J C. Airborne microplastics: Consequences to human health? [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 234: 115-126

[57] Mastrangelo G, Fedeli U, Fadda E, et al. Lung cancer risk in workers exposed to poly(vinyl chloride) dust: A nested case-referent study [J]. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2003, 60(6): 423-428

[58] Anyfantis I D, Rachiotis G, Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function among Greek cotton industry workers: A cross-sectional study [J]. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2017, 8(1): 32-38

[59] Song Y, Li X, Du X. Exposure to nanoparticles is related to pleural effusion, pulmonary fibrosis and granuloma [J]. The European Respiratory Journal, 2009, 34(3): 559-567

[60] Oo T W, Thandar M, Htun Y M, et al. Assessment of respiratory dust exposure and lung functions among workers in textile mill (Thamine), Myanmar: A cross-sectional study [J]. BMC Public Health, 2021, 21(1): 673

[61] Braun T, Ehrlich L, Henrich W, et al. Detection of microplastic in human placenta and meconium in a clinical setting [J]. Pharmaceutics, 2021, 13(7): 921

[62] Fournier S B, D’Errico J N, Adler D S, et al. Nanopolystyrene translocation and fetal deposition after acute lung exposure during late-stage pregnancy [J]. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 2020, 17(1): 55

[63] Hu J N, Qin X L, Zhang J W, et al. Polystyrene microplastics disturb maternal-fetal immune balance and cause reproductive toxicity in pregnant mice [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2021, 106: 42-50

[64] Hou J Y, Lei Z M, Cui L L, et al. Polystyrene microplastics lead to pyroptosis and apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells via NLRP3/Caspase-1 signaling pathway in rats [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 212: 112012

[65] Li S D, Wang Q M, Yu H, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce blood-testis barrier disruption regulated by the MAPK-Nrf2 signaling pathway in rats [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2021, 28(35): 47921-47931

[66] Kwon W, Kim D, Kim H Y, et al. Microglial phagocytosis of polystyrene microplastics results in immune alteration and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 807(Pt 2): 150817

[67] Lu L, Wan Z Q, Luo T, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 631-632: 449-458

[68] Deng Y F, Zhang Y, Lemos B, et al. Tissue accumulation of microplastics in mice and biomarker responses suggest widespread health risks of exposure [J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 46687

[69] Barhoumi B, Tedetti M, Heimbürger-Boavida L E, et al. Chemical composition and in vitro aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated activity of atmospheric particulate matter at an urban, agricultural and industrial site in North Africa (Bizerte, Tunisia) [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 258: 127312

[70] Borges-Ramírez M M, Escalona-Segura G, Huerta-Lwanga E, et al. Organochlorine pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, metals and metalloids in microplastics found in regurgitated pellets of black vulture from Campeche, Mexico [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 801: 149674

[71] Menéndez-Pedriza A, Jaumot J, Bedia C. Lipidomic analysis of single and combined effects of polyethylene microplastics and polychlorinated biphenyls on human hepatoma cells [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 421: 126777

[72] Sharma M D, Elanjickal A I, Mankar J S, et al. Assessment of cancer risk of microplastics enriched with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 398: 122994

[73] Khalid N, Aqeel M, Noman A, et al. Interactions and effects of microplastics with heavy metals in aquatic and terrestrial environments [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 290: 118104

[74] Cheng Y, Lu J, Fu S, et al. Enhanced propagation of intracellular and extracellular antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater by microplastics [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 292: 118284

[75] Amato-Lourenço L F, de Souza Xavier Costa N, Dantas K C, et al. Airborne microplastics and SARS-CoV-2 in total suspended particles in the area surrounding the largest medical centre in Latin America [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 292(Pt A): 118299