在我国,人们每天约80%~90%的时间在室内环境中度过[1],室内空气质量对于人群健康具有重要影响。据世界卫生组织(WHO)报告,全球每年有约400万人因室内空气污染导致的疾病而过早死亡[2]。而人的一生中约有1/3的时间在睡眠中度过,卧室是我们常处的室内环境之一,暴露于卧室中的空气污染物严重威胁人体健康。

过去的几十年里,包括家具、电子产品、建筑材料和日用品在内的消费品大量涌入到室内环境中,这些消费品往往含有大量添加剂,如阻燃剂、增塑剂、润滑剂、杀虫剂和香料等[3]。多数添加剂是半挥发性有机物(SVOCs),接触它们可能会对人体健康造成不利影响。例如,邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)会导致生殖问题、呼吸道症状、儿童肥胖和神经发育障碍[4-5];多环芳烃(PAHs)会导致心血管疾病、癌症以及DNA和脂质的氧化损伤[6-8];室内灰尘中的有机磷酸酯(OPEs)被发现与哮喘和过敏性鼻炎的患病率上升显著相关[9]。

SVOCs会随着时间从消费品中释放到室内环境中,在空气、灰尘和物体表面重新分配,而灰尘是室内SVOCs重要的汇[3]。Zhang等[7]在广州市的室内灰尘中检出16种PAHs,菲和萘被发现是灰尘中主要的PAHs。Zhu等[10]调查了从我国6个地理区域收集的室内灰尘中的9种PAEs,发现邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯浓度水平最高。Hu等[11]在广州不同室内环境的灰尘中检出8种OPEs和7种有机磷酸二酯,磷酸三(2-氯异丙基)酯和磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯是主要污染物。Arnold等[12]在美国和葡萄牙的养老机构收集的灰尘中分析了120种SVOCs,发现OPEs、PAHs和溴化阻燃剂含量最多。现有研究多集中关注灰尘中有限几类的SVOCs,关于SVOCs的复合污染水平以及相应健康风险尚不明确。

本研究从19个家庭卧室中采集沉降灰尘样品,使用气相色谱质谱仪(GC-MS)高通量筛查室内灰尘中895种SVOCs的存在水平,甄别主要污染物。比较本研究与前人研究中室内SVOCs的检出浓度,分析其潜在来源。根据美国环境保护局(US EPA)开发的健康风险评价模型,评价了灰尘中SVOCs对成人和幼儿的非致癌和致癌风险,为保护室内人群健康提供基础数据。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 样品采集

2021年8月和9月,招募志愿者,在我国13个省市的19户志愿者家庭卧室中采集了灰尘样品。通过问卷调查获得采样家庭的相关信息,调查显示:16户家庭处于交通不繁忙地带;8个卧室每天的通风时间为13~24 h,3个卧室通风时间为7~12 h,其余卧室通风时间不足6 h;所有卧室采样期间均未使用空气净化器;13个卧室铺设瓷砖,6个卧室铺设木质地板。

在卧室地板上,使用预先用甲醇清洗过的毛刷采集了19个沉降灰尘样品,将样品用锡箔包裹并密封在聚乙烯袋中,在-20 ℃下储存至提取和分析。

1.2 样品前处理及分析

取0.1 g灰尘放入玻璃离心管中,加入7种氘代回收率替代物(2,4-二氯苯酚-d3、芴-d10、硝基苯-d5、蒽-d10、对三联苯-d14、芘-d10,购自日本Shimadzu;磷酸三苯酯-d15,购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer),加入8 mL二氯甲烷(美国Sigma,色谱纯),超声20 min(昆山市超声仪器有限公司,KQ-300E型超声波清洗器)。提取液以4 000 r·min-1离心15 min(湖南湘仪实验室仪器开发有限公司,湘仪TDZ5-WS),上清液转移到另一个离心管中。再次加入8 mL二氯甲烷,按照相同步骤重复提取一次。合并所得溶液,使用硫酸钠干燥柱(美国Agilent,Bond Elut JR-Sodium sulf,1.4g)进行过滤。过滤液使用氮气缓慢浓缩至1 mL,加入4 mL正己烷(美国Sigma,色谱纯),摇匀后继续浓缩至0.5 mL,加入6种氘代物质(1,4-二氯苯-d4、萘-d8、苊-d10、菲-d10、荧蒽-d10和![]() -d12,购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer)和六甲基苯(购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer)作为内标,将溶液通过尼龙膜(天津津腾,nylon 66,0.22 μm)过滤至棕色小瓶,待仪器分析。

-d12,购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer)和六甲基苯(购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer)作为内标,将溶液通过尼龙膜(天津津腾,nylon 66,0.22 μm)过滤至棕色小瓶,待仪器分析。

本研究对灰尘中895种SVOCs进行高通量筛查。使用GC-MS(美国Agilent,6890N-5975)在全扫描模式(EI源)下分析灰尘样品中的SVOCs,结合自动识别与定量系统(AIQS)数据库[13]对886种SVOCs进行靶标筛查。该数据库中含有403种农药、78种PAHs、63种多氯联苯、54取代苯酚、50种酯、34种取代苯胺、26种脂肪酸、26种正构烷烃、20种取代硝基苯、17种醇、17种药物及个人护理品、16种取代联苯、15种氯苯、14种醚、13种PAEs、9种OPEs、6种酰胺和34种其他SVOCs的信息。分析时,使用HP-5MS毛细管柱(30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm)分离目标物,采用不分流进样,进样体积为2 μL。具体的仪器条件参考Li等[14]的研究。

此外,使用GC-MS(日本Shimadzu,QP2020)在选择离子模式(EI源)下分析了室内灰尘中的9种OPEs(磷酸三苯酯(TPHP)、磷酸三(2-氯异丙基)酯(TCIPP)、磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯(TCEP)、磷酸三甲苯酯(TCP)、磷酸三(丁氧基乙基)酯(TBOEP)、磷酸三辛酯(TEHP)、磷酸三(1,3-二氯异丙基)酯(TDCIPP)、磷酸三丁酯(TBP)、2-乙基己基二苯基磷酸酯(EHDPP),标准品购自德国Dr.Ehrenstorfer)。使用SH-RXI-5silMS毛细管柱(30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm)分离目标物。升温程序为:初始温度60 ℃,保持1 min,以12 ℃·min-1升温至312 ℃,保持10 min。采用不分流进样,进样体积为1 μL。

1.3 质量保证和质量控制

AIQS数据库是由门上希和夫教授等[13]开发,数据库中包含886种目标物的标准品的保留时间、校准曲线和质谱信息。使用该数据库,可以在不使用标准品的情况下自动识别实际样品中的目标物,前提条件是要保证测样时GC-MS性能与用于构建数据库的仪器性能相当。该数据库已成功应用于定量分析地下水[14]和大气颗粒物[15]等样品中的SVOCs。

为确保从AIQS数据库获得的目标物定性和定量结果的可靠性,需要确认本研究中使用的Agilent GC-MS仪器性能。在实际样品测量前,使用性能检查标准液(NAGINATA Criteria sample mix Ⅱ,购自日本林纯药工业株式会社)评价仪器进样口衬管和色谱柱的惰性以及仪器响应情况[13]。该标准液中,含有24种正构烷烃(C10~C33),用于保留时间定性;16种物质(表1)用于评价仪器性能;6种氘代物(与样品前处理所加氘代内标相同)用作内标。评价结果(表1)显示:16种化合物的保留时间漂移(偏离数据库设定的保留时间)范围为-0.77~1.10 s;14种物质的仪器响应为0.66~1.26(相对于内标的理想响应为1)。这些结果表明,使用GC-MS结合AIQS数据库对886种SVOCs进行靶标分析,能够产生可靠的定性和定量结果。

表1 GC-MS系统的性能

Table 1 Performance of the GC-MS system

序号No.化合物Compound保留时间漂移/sRetention-time shift/s响应Response1敌菌丹 Captafol-0.100.942恶唑磷 Isoxathion-0.431.2632,4-二氯苯胺 2,4-dichloroanilin0.040.9842,4-二硝基苯胺 2,4-dinitroaniline-0.031.145五氯酚 Pentachlorophenol-0.110.356西玛津 Simazine-0.411.017杀螟松 Fenitrothion0.540.708十氟三苯基磷 Decafluorotriphenylphosphine1.100.8392,6-二氯苯酚 2,6-dichlorophenol0.090.73102,6-二甲基苯胺 2,6-dimethylaniline-0.771.1011苯并噻唑 Benzothiazole-0.360.9612邻苯二甲酸丁苄酯 Butyl benzyl phtalate-0.101.0913邻苯二甲酸二乙酯 Diethyl phthalate0.320.9914磷酸三丁酯 Tributyl phosphate0.350.8015磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯 Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate0.480.5516甲基毒死蜱 Chlorpyrifos-methyl0.230.66

为评估实验室分析过程中的潜在污染,本研究分析了3个空白样品(仅添加溶剂和内标)。在空白样品中检出23种SVOCs,有13种为正构烷烃(C12~C24)。23种SVOCs的平均检出质量为0.14~9.7 μg,标准偏差为0.0026~0.80 μg。如果样品中的目标物浓度是空白中平均浓度的2倍,则通过减去空白平均浓度来报告浓度。否则,目标物将被视为未检出。

在4个灰尘样品中加入回收率替代物,以检查方法回收率。2,4-二氯苯酚-d3的回收率为(88.6±6.1)%,芴-d10的回收率为(79.8±5.2)%,硝基苯-d5的回收率为(68.9±7.1)%,蒽-d10的回收率为(79.3±5.9)%,对三联苯-d14的回收率为(88.4±6.2)%,芘-d10的回收率为(70.6±4.8)%,磷酸三苯酯-d15的回收率为(97.7±9.9)%。回收率不用于校正目标物的检出浓度。

1.4 人体暴露和健康风险评价

不同环境介质中的SVOCs会通过不同的暴露途径进入人体并导致健康风险。室内灰尘中的SVOCs可以通过经口摄入、呼吸吸入和皮肤吸收这3种途径进入人体。因此,本研究在暴露评价中分别计算了成人和幼儿(0~2岁,在卧室睡眠时间长)的经口摄入(CDIing)、呼吸吸入(CDIinh)和皮肤吸收(CDIder)的慢性每日摄入剂量(CDI)(ng·kg-1·d-1)[16]:

CDIing=(c×IngR×f×EF×ED)/(BW×AT×1000)

(1)

CDIinh=(c×InhR×f×EF×ED×1000)/(BW×AT×PEF)

(2)

CDIder=(c×AF×ABS×SA×f×EF×ED)/(BW×AT×1000)

(3)

CDItotal=CDIing+CDIinh+CDIder

(4)

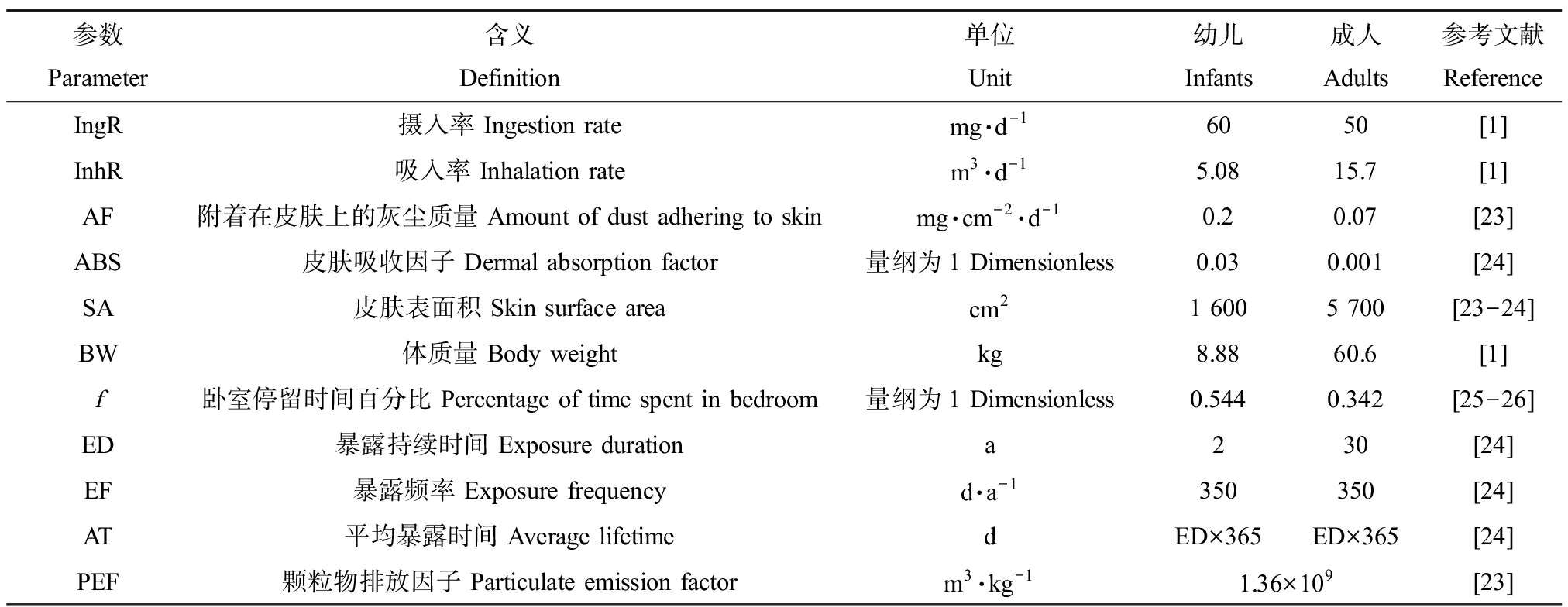

式中:c为灰尘样品中SVOCs的检出浓度(ng·g-1);IngR是灰尘摄入率(mg·d-1);InhR是吸入率(m3·d-1);AF是附着在皮肤上的灰尘质量(mg·cm-2·d-1);ABS是皮肤吸收因子;SA是暴露的皮肤表面积(cm2);BW是体质量(kg);f是每天人群每天花在卧室里的时间百分比;ED是暴露持续时间(a);EF是暴露频率(d·a-1);AT是平均总暴露时间(d);PEF是颗粒物排放因子(m3·kg-1)。相关的暴露参数取值如表2所示。

表2 人体暴露评价相关参数

Table 2 Parameters for human exposure assessment

参数Parameter含义Definition单位Unit幼儿Infants成人Adults参考文献ReferenceIngR摄入率 Ingestion ratemg·d-16050[1]InhR吸入率 Inhalation ratem3·d-15.0815.7[1]AF附着在皮肤上的灰尘质量 Amount of dust adhering to skinmg·cm-2·d-10.20.07[23]ABS皮肤吸收因子 Dermal absorption factor量纲为1 Dimensionless0.030.001[24]SA皮肤表面积 Skin surface areacm21 6005 700[23-24]BW体质量 Body weightkg8.8860.6[1]f卧室停留时间百分比 Percentage of time spent in bedroom量纲为1 Dimensionless0.5440.342[25-26]ED暴露持续时间 Exposure durationa230[24]EF暴露频率 Exposure frequencyd·a-1350350[24]AT平均暴露时间 Average lifetimedED×365ED×365[24]PEF颗粒物排放因子 Particulate emission factorm3·kg-11.36×109[23]

非致癌风险评价中,使用摄入(HQing)、吸入(HQinh)和皮肤吸收(HQder)这3种暴露途径的危害商(HQ)[17]来表征单体SVOC的风险,危害指数(HI)则为3种暴露途径的风险加和:

HQing=CDIing/RfD

(5)

HQinh=CDIinh/RfD

(6)

HQder=CDIder/RfD

(7)

HI=HQing+HQinh+HQder

(8)

式中:RfD是SVOCs的慢性毒性参考剂量(ng·kg-1·d-1),该数据可从美国的综合风险信息系统(IRIS)[18]和风险评估信息系统(RAIS)[19]等数据库获得,当数据库中缺失相关SVOCs的RfD时,本研究使用由Wignall等[20]开发的定量结构-活性关系模型(QSAR)预测得到的RfD,用于风险评价。非致癌风险被划分为高风险(HQ>1)、中等风险(0.1≤HQ≤1)、低风险(0.01≤HQ≤0.1)和可忽略的风险(HQ<0.01)[21]。

致癌风险评价中,成人的慢性每日摄入量被用于计算终生致癌风险(CR),方法如下[17]:

CRing=CDIing×CSF

(9)

CRinh=CDIinh×CSF

(10)

CRder=CDIder×CSF

(11)

CRtotal=CRing+CRinh+CRder

(12)

式中:CRing、CRinh和CRder分别表示经口摄入、呼吸吸入和皮肤吸收引起的致癌风险;CSF为致癌斜率因子(kg·d·ng-1),该数据也可从相关的数据库获得,当数据库中缺失该数据时,使用由Wignall等[20]开发的模型预测值。由于缺乏不同暴露途径下SVOCs的CSF值,本研究均使用经口暴露的CSF来评价检出物的致癌风险。致癌风险分为不可接受的风险(CR>10-4)、潜在风险(10-6≤CR≤10-4)和可忽略的风险(CR<10-6)[21-22]。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 卧室灰尘中SVOCs的存在水平

在19个灰尘样品中共检出了85种SVOCs,包括20种正构烷烃、12种PAHs、6种PAEs、8种OPEs、7种醇、6种取代苯、9种酚、9种农药、4种酯、2种脂肪酸和2种其他类。灰尘中检出的SVOCs的总浓度范围为92~1.4×103μg·g-1(中值:4.3×102μg·g-1),每户家庭灰尘中至少检出31种SVOCs,最多可以检出43种SVOCs。本研究分析了不同种类SVOCs的浓度对总浓度的贡献(图1),PAEs是灰尘中含量最丰富的SVOCs,对总浓度的平均贡献达到了(40.9±11.7)%;其次为正构烷烃,平均贡献为(29.8±9.7)%;其余种类的SVOCs的平均贡献均不超过10%。

图1 不同家庭室内灰尘中检出的半挥发性有机物的组成

注:PAHs表示多环芳烃;OPEs表示有机磷酸酯;PAE表示邻苯二甲酸酯。

Fig.1 Composition profile of semi-volatile organic compounds detected in indoor dust from different homes

Note: PAHs stands for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; OPEs stands for organophosphate esters; PAEs stands for phthalates.

6种PAEs的总浓度范围为28~5.3×102μg·g-1(中值:1.4×102μg·g-1)。经浓度贡献分析(图2),邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯(DEHP,检出率:100%)、邻苯二甲酸二丁酯(DBP,78.9%)和邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯(DIBP,100%)分别贡献了总浓度的(63.1±14.5)%、(25.6±17.1)%和(10.4±10.2)%,是灰尘中最主要的3种PAEs。邻苯二甲酸二甲酯(DMP,47.4%)和邻苯二甲酸二乙酯(DEP,78.9%)尽管也在多个灰尘样品中检出,但二者加和贡献仅为(0.8±1.3)%。此外,仅在一个样品中检出邻苯二甲酸二正辛酯(DnOP)。

图2 不同家庭室内灰尘中检出的邻苯二甲酸酯的组成

注:DEHP表示邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯;DBP表示邻苯二甲酸二丁酯;DIBP表示邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯;DMP表示邻苯二甲酸二甲酯;DEP表示邻苯二甲酸二乙酯;DnOP表示邻苯二甲酸二正辛酯。

Fig.2 Composition profile of phthalates detected in indoor dust from different homes

Note: DEHP stands for bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate; DBP stands for dibutyl phthalate; DIBP stands for diisobutyl phthalate; DMP stands for dimethyl phthalate; DEP stands for diethyl phthalate; DnOP stands for di-n-octyl phthalate.

检出的正构烷烃为C12、C14和C16~C33,总浓度范围为34~2.5×102μg·g-1(中值:1.2×102μg·g-1)。为分析灰尘中正构烷烃的可能来源,本研究计算了碳优势指数(CPI,奇数碳的正构烷烃浓度之和与偶数碳的正构烷烃浓度之和的比值)和主峰碳(Cmax,含量最丰富的正构烷烃的碳数)2个参数。计算出的CPI范围为0.9~2.9(中值:1.8)。从11个样品中识别出的Cmax为C29,其次在5个样品中识别出的Cmax为C31。

鲸蜡醇(检出率:84.2%)、月桂醇(73.7%)和1-壬醇(63.2%)是灰尘中最常检出的3种醇,中值浓度分别达到17、8.5和1.3 μg·g-1。棕榈酸甲酯(73.7%)和乙酰柠檬酸三丁酯(ATBC,63.2%)则是最常检出的酯,中值浓度分别达到1.3 μg·g-1和6.1 μg·g-1。检出2种脂肪酸,肉豆蔻酸和硬脂酸,但检出率均低于20%。

壬基酚和苯乙烯化苯酚是灰尘中检出率最高的酚类污染物,二者检出率均为57.9%,中值浓度分别为4.4 μg·g-1和2.5 μg·g-1。此外,还检出2,6-二叔丁基对甲酚、三氯生等,但检出率均低于30%。

灰尘中检出的农药均为各类杀虫剂或杀虫剂助剂(包括3种拟除虫菊酯、避蚊胺和增效醚等),但检出率均未超过50%。仅氯菊酯的检出率达到42.1%,其最高检出浓度达29 μg·g-1。

检出的OPEs的总浓度范围为0.11~4.8×102μg·g-1(中值:1.6 μg·g-1)。其中,TCIPP、TCEP、TPHP、TDCIPP和EHDPP均被100%检出,它们共同贡献了总浓度的(87.3±19.3)%。TCIPP是灰尘中主要的OPE,平均贡献为(33.5±21.4)%。

所有的灰尘样品中都检出PAHs,总浓度范围为0.18~8.3 μg·g-1(中值:2.0 μg·g-1)。低环PAHs检出率相对较高,如2-甲基萘(2环,84.2%)、菲(3环,78.9%)和萘(2环,57.9%),中值浓度分别为0.43、0.86和0.18 μg·g-1。菲是灰尘中的最主要PAH,平均贡献为(36.6±21.4)%。苯乙酮是检出率最高的取代苯(84.2%),中值浓度为0.39 μg·g-1。

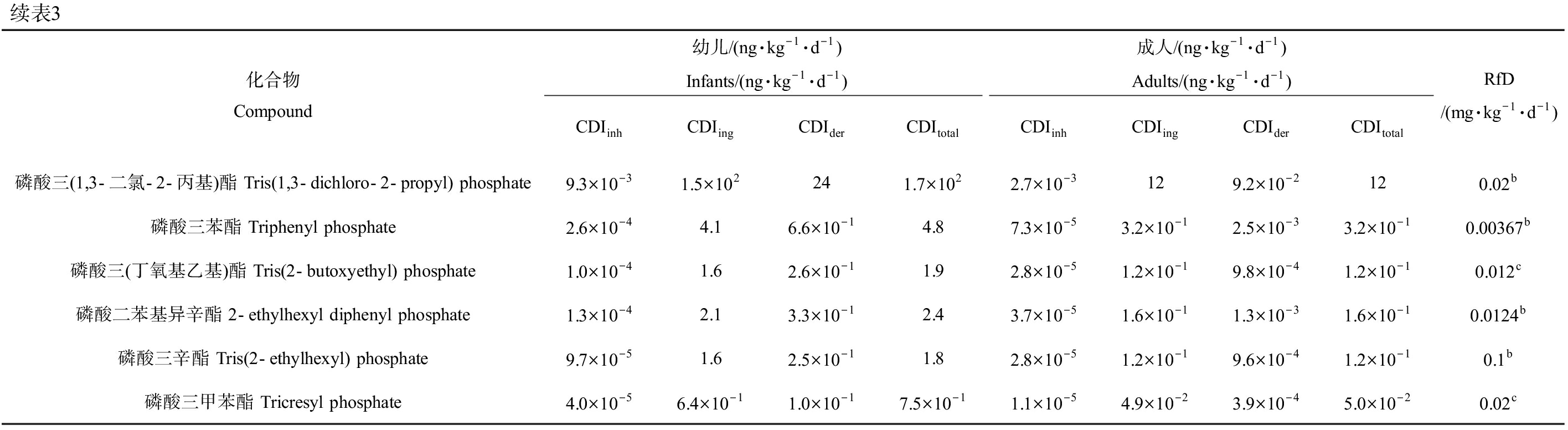

2.2 卧室灰尘中SVOCs的健康风险

本研究基于灰尘样品中的第95分位浓度,对检出率>10%的38种SVOCs进行人体暴露和健康风险评价。成人和幼儿通过摄入、吸入和皮肤吸收这3种途径的慢性每日摄入量如表3所示。3种途径中,吸入途径的摄入量远比另外2种途径低,可忽略不计。暴露量计算结果表明,幼儿和成人对DEHP的摄入量最高,分别达到7.5×102ng·kg-1·d-1和50 ng·kg-1·d-1。幼儿的摄入量均比成人的高,因此幼儿更容易受到室内灰尘中SVOCs的健康威胁。

表3 幼儿和成人的慢性每日摄入剂量(CDI)及对应的参考剂量(RfD)

Table 3 Chronic daily intake(CDI)and corresponding reference dose(RfD)for infants and adults

化合物 Compound幼儿/(ng·kg-1·d-1) Infants/(ng·kg-1·d-1)成人/(ng·kg-1·d-1) Adults/(ng·kg-1·d-1)CDIinhCDIingCDIderCDItotalCDIinhCDIingCDIderCDItotalRfD/(mg·kg-1·d-1)邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯 Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate4.0×10-26.5×1021.0×1027.5×1021.2×10-2504.0×10-1500.02a邻苯二甲酸二丁酯 Dibutyl phthalate2.9×10-24.7×102755.4×1028.3×10-3362.9×10-1360.1a邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯 Diisobutyl phthalate9.9×10-31.6×102251.8×1022.8×10-3129.7×10-2120.4d邻苯二甲酸二甲酯 Dimethyl phthalate3.4×10-45.48.6×10-16.39.6×10-54.1×10-13.3×10-34.2×10-10.35d邻苯二甲酸二乙酯 Diethyl phthalate5.5×10-48.81.4101.6×10-46.8×10-15.4×10-36.8×10-10.8c苯乙酮 Acetophenone2.6×10-44.26.7×10-14.97.5×10-53.2×10-12.6×10-33.3×10-10.1a苯并噻唑 Benzothiazole5.3×10-58.6×10-11.4×10-111.5×10-56.6×10-25.3×10-46.6×10-20.00492c邻苯二甲酸 Phthalic acid3.8×10-3619.7701.1×10-34.73.7×10-24.70.5b肉豆蔻酸 Myristic acid2.2×10-23.5×102554.0×1026.1×10-3272.1×10-1270.0181c2-甲基萘 2-methyl naphthalene1.3×10-42.13.4×10-12.53.8×10-51.6×10-11.3×10-31.7×10-10.004a联苯 Biphenyl5.8×10-59.3×10-11.5×10-11.11.7×10-57.2×10-25.7×10-47.2×10-20.5a菲Phenanthrene5.4×10-48.61.4101.5×10-46.6×10-15.3×10-36.7×10-10.00656c萘 Naphthalene4.6×10-47.41.28.61.3×10-45.7×10-14.5×10-35.7×10-10.02a荧蒽 Fluoranthene2.0×10-43.15.0×10-13.75.6×10-52.4×10-11.9×10-32.4×10-10.04a芘 Pyrene1.7×10-42.74.3×10-13.14.8×10-52.1×10-11.6×10-32.1×10-10.03a月桂醇 Lauryl alcohol4.1×10-36711771.2×10-35.14.1×10-25.20.0181c1-壬醇 1-nonanol3.0×10-3487.6558.4×10-43.72.9×10-23.70.0154a硬脂醇 Stearyl alcohol1.2×10-21.9×102312.2×1023.4×10-3151.2×10-1150.0202c鲸蜡醇 Cetyl alcohol7.1×10-31.1×102181.3×1022.0×10-38.87.0×10-28.90.0171c辛醇 Octanol2.7×10-44.47.0×10-15.17.8×10-53.4×10-12.7×10-33.4×10-10.0161c苯甲醇 Benzyl alcohol6.9×10-4111.8132.0×10-48.5×10-16.8×10-38.5×10-10.1a棕榈酸甲酯 Methyl palmitate1.0×10-3162.6192.9×10-41.31.0×10-21.30.0283c硬脂酸甲酯 Methyl stearate1.0×10-3162.6192.9×10-41.29.9×10-31.30.0282c己二酸双(2-乙基己基)酯 Bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate1.3×10-3213.3243.7×10-41.61.3×10-21.60.6a乙酰柠檬酸三丁酯 Acetyl tri-n-butyl citrate1.1×10-21.7×102282.0×1023.1×10-3131.1×10-1130.0403c2,6-二叔丁基对甲酚 Butylated hydroxytoluene5.6×10-491.4101.6×10-46.9×10-15.5×10-37.0×10-10.3b壬基酚 Nonyl phenol3.4×10-3558.9649.8×10-44.23.4×10-24.30.0171c苯乙烯化苯酚 Styrenated phenol4.7×10-37612881.3×10-35.84.7×10-25.90.00123c氯菊酯Permethrin6.1×10-398161.1×1021.7×10-37.56.0×10-27.60.05a避蚊胺 Diethyltoluamide1.8×10-42.94.7×10-13.45.2×10-52.2×10-11.8×10-32.3×10-10.0171c磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯 Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate5.3×10-48.51.49.91.5×10-46.5×10-15.2×10-36.6×10-10.007b磷酸三(1-氯-2-丙基)酯 Tris(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate2.5×10-3416.5477.2×10-43.12.5×10-23.20.01b

续表3化合物 Compound幼儿/(ng·kg-1·d-1) Infants/(ng·kg-1·d-1)成人/(ng·kg-1·d-1) Adults/(ng·kg-1·d-1)CDIinhCDIingCDIderCDItotalCDIinhCDIingCDIderCDItotalRfD/(mg·kg-1·d-1)磷酸三(1,3-二氯-2-丙基)酯 Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate9.3×10-31.5×102241.7×1022.7×10-3129.2×10-2120.02b磷酸三苯酯 Triphenyl phosphate2.6×10-44.16.6×10-14.87.3×10-53.2×10-12.5×10-33.2×10-10.00367b磷酸三(丁氧基乙基)酯 Tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate1.0×10-41.62.6×10-11.92.8×10-51.2×10-19.8×10-41.2×10-10.012c磷酸二苯基异辛酯 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate1.3×10-42.13.3×10-12.43.7×10-51.6×10-11.3×10-31.6×10-10.0124b磷酸三辛酯 Tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate9.7×10-51.62.5×10-11.82.8×10-51.2×10-19.6×10-41.2×10-10.1b磷酸三甲苯酯 Tricresyl phosphate4.0×10-56.4×10-11.0×10-17.5×10-11.1×10-54.9×10-23.9×10-45.0×10-20.02c

注:CDIinh表示吸入量;CDIing表示经口摄入量;CDIder表示皮肤吸收量;CDItotal表示总摄入量;RfD表示参考剂量;a数据来自综合风险信息系统[18];b数据来自风险评估信息系统[19];cWignall等[20]开发的定量结构-活性关系模型预测值;d数据来自文献[14]。

Note: CDIinh stands for intake via inhalation; CDIingstands for intake via ingestion; CDIderstands for intake via dermal absorption; CDItotalstands for total intake; RfD stands for reference dose; athe data were from the Integrated Risk Information System[18]; bthe data were from the Risk Assessment Information System[19]; cthe data were predicted using the quantitative structure-activity relationship model developed by Wignall et al.[20]; dthe data were from the literature[14].

针对这38种SVOCs,本研究从各毒性数据库和文献中获取RfD值,评价它们的非致癌风险。结果显示,SVOCs的非致癌风险(HI)均未超过0.1。成人的非致癌风险最高仅为4.8×10-3,来自苯乙烯化苯酚,可忽略不计。4种SVOCs被发现会对儿童造成低风险,包括苯乙烯化苯酚(HI=7.2×10-2)、DEHP(HI=3.8×10-2)、肉豆蔻酸(HI=2.2×10-2)和硬脂醇(HI=1.1×10-2),其风险主要是摄入灰尘导致的。

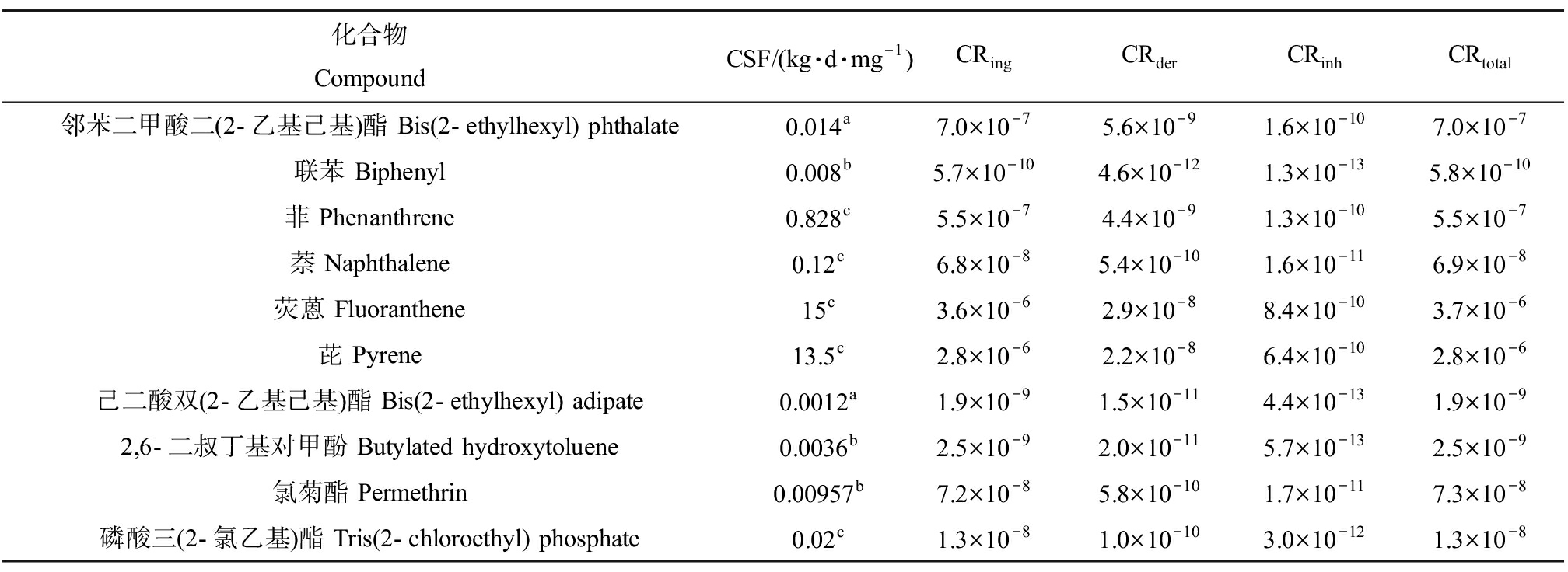

根据WHO的致癌物清单,在灰尘中识别出10种检出率>10%的致癌物,评价了它们的致癌风险(表4)。其中,2种4环PAHs,荧蒽(3.7×10-6)和芘(2.8×10-6)的风险被发现超出可接受水平(10-6),会造成潜在的致癌风险,其致癌风险同样是由摄入灰尘导致的。其余SVOCs的致癌风险均可忽略。

表4 半挥发性有机物的致癌斜率因子(CSF)和致癌风险(CR)

Table 4 Carcinogenic slope factor(CSF)and carcinogenic risk(CR)of semi-volatile organic compounds

化合物CompoundCSF/(kg·d·mg-1)CRingCRderCRinhCRtotal邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基己基)酯 Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate0.014a7.0×10-75.6×10-91.6×10-107.0×10-7联苯 Biphenyl0.008b5.7×10-104.6×10-121.3×10-135.8×10-10菲 Phenanthrene0.828c5.5×10-74.4×10-91.3×10-105.5×10-7萘 Naphthalene0.12c6.8×10-85.4×10-101.6×10-116.9×10-8荧蒽 Fluoranthene15c3.6×10-62.9×10-88.4×10-103.7×10-6芘 Pyrene13.5c2.8×10-62.2×10-86.4×10-102.8×10-6己二酸双(2-乙基己基)酯 Bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate0.0012a1.9×10-91.5×10-114.4×10-131.9×10-92,6-二叔丁基对甲酚 Butylated hydroxytoluene0.0036b2.5×10-92.0×10-115.7×10-132.5×10-9氯菊酯 Permethrin0.00957b7.2×10-85.8×10-101.7×10-117.3×10-8磷酸三(2-氯乙基)酯 Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate0.02c1.3×10-81.0×10-103.0×10-121.3×10-8

注:CSF表示致癌斜率因子;CRing表示摄入致癌风险;CRder表示皮肤吸收致癌风险;CRinh表示吸入致癌风险;CRtotal表示总致癌风险;a数据来自综合风险信息系统[18];b数据来自风险评估信息系统[19];cWignall等[20]开发的定量结构-活性关系模型预测值。

Note: CSF stands for carcinogenic slope factor; CRingstands for carcinogenic risk via ingestion; CRderstands for carcinogenic risk via dermal absorption; CRinhstands for carcinogenic risk via inhalation; CRtotalstands for total carcinogenic risk; athe data were from the Integrated Risk Information System[18]; bthe data were from the Risk Assessment Information System[19]; cthe data were predicted using the quantitative structure-activity relationship model developed by Wignall et al.[20]

3 讨论(Discussion)

本研究首次对我国家庭室内灰尘中的895种SVOCs开展了高通量筛查,阐明了卧室灰尘中SVOCs的复合污染概况。通过浓度贡献分析,从灰尘样品中检出的85种SVOCs中,识别出PAEs是最主要的污染物。此外,本研究对比了不同国家和地区室内灰尘中SVOCs的存在水平,并分析其潜在来源。

3.1 卧室灰尘中SVOCs的存在水平及来源分析

本研究中PAEs的检出水平(中值:1.4×102μg·g-1),低于在加拿大(626 μg·g-1)[27]、美国(288 μg·g-1)[28]。同时,本研究PAEs浓度也低于中国台湾地区(497 μg·g-1)[29]和广州市(241 μg·g-1)[30]的检出水平,但高于从我国6个地理区域(54 μg·g-1)[10]和7个地理区域(105 μg·g-1)[31]收集的室内灰尘中的浓度。本研究灰尘中PAEs组成与我国6个区域(DEHP:49.5%~89.4%,DBP:7.00%~31.2%,DIBP:3.20%~23.8%)[10]和我国7个区域(DEHP:60.4%,DBP:28.0%,DIBP:10.5%)[31]的组成相似,表明我国不同地区室内灰尘中的PAEs具有相似来源。DEHP具有较高的辛醇-空气分配系数(logKoa=12.56,来自EPIWEB 4.1),容易被灰尘吸附,是灰尘中最丰富的PAE。它还被发现是美国、法国、瑞典和日本等大多数国家灰尘中主要的PAE[32]。DEHP和DBP广泛用作聚氯乙烯塑料(PVC)、建筑材料、电子产品和玩具等消费品中的增塑剂,而DEP和DMP不用作增塑剂,用作化妆品、家庭和个人护理产品中的添加剂[32]。灰尘中DEHP和DBP的高检出率和高浓度,表明增塑剂的大规模使用导致PAEs成为室内主要的SVOCs。

由于碳数小的正构烷烃挥发性强,不易被颗粒物吸附,本研究中碳数<23的正构烷烃在灰尘中检出率均低于40%。高等植物排放的正构烷烃碳数一般>24,具有较高的Cmax,奇偶优势明显;化石燃料成熟度较高,燃烧排放的正构烷烃碳数一般<24,有较低的的Cmax[33]。本研究识别出的Cmax为C29和C31,这表明本研究中检出的正构烷烃明显受到植物源的影响。此外,一般化石燃料燃烧产生的正构烷烃的CPI值接近1,而植物源的正构烷烃CPI值>5[33]。本研究中正构烷烃的CPI中值为1.8(0.9~2.9),这说明化石燃料也是室内正构烷烃污染的重要来源。

目前,室内环境中醇污染相关的研究较少。本研究在灰尘中检出鲸蜡醇、月桂醇和1-壬醇等7种醇类物质。有研究指出,鲸蜡醇、月桂醇和1-壬醇常作为香料、乳化剂和表面活性剂等添加在各种化妆品和个人护理品中(如洗发水、肥皂和润肤乳)[34-35]。生活用品中添加剂造成的室内污染问题需要进一步的关注。

室内环境中的ATBC和棕榈酸甲酯检出率较高,分别为63.2%和73.7%。本研究中ATBC的浓度(中值:6.1 μg·g-1)高于广州地区的浓度(2.68 μg·g-1)[30],但远低于美国的检出浓度(271 μg·g-1)[36]。此外,这应是首次在室内灰尘中筛查出棕榈酸甲酯。ATBC是PAEs的主要替代增塑剂[36],棕榈酸甲酯则是PVC和橡胶中一种重要的稳定剂和润滑剂[37-38]。灰尘中这2种酯可能主要来自于塑料或橡胶制品。

酚在住宅环境中普遍存在[39]。本研究在一半以上的家庭中检出壬基酚和苯乙烯化苯酚。壬基酚广泛用作日用化学品和纺织品中的表面活性剂,也作为抗氧化剂加入塑料制品,是环境中普遍检出的雌激素物质[40]。本研究中壬基酚检出浓度(4.4 μg·g-1)低于加拿大的部分地区的检出浓度(4.9 μg·g-1)[41],高于日本的部分地区的检出浓度(3.1 μg·g-1)[42],且比我国2013年部分地区研究的检出浓度(3 ng·g-1)[43]高出1 000多倍。此外,苯乙烯化苯酚常用作橡胶防老剂(抗氧化剂),是酚类防老剂中使用较广泛的品种[44]。然而,目前关于室内灰尘中苯乙烯化苯酚的发现较少,需要进一步研究室内环境中该类物质的污染水平。

本研究中OPEs的检出浓度(中值:1.6 μg·g-1)高于成都(0.5 μg·g-1)[45]和广州(1.4 μg·g-1)[30]地区灰尘中浓度,但低于上海(11.5 μg·g-1)[46]、大连和通辽(2.5 μg·g-1)[47]地区灰尘中浓度。本研究发现氯化OPEs(TCIPP、TCEP和TDCIPP)和非氯化OPEs(TPHP和EHDPP)都与DEHP具有显著相关性(P<0.05)。已有研究表明,氯化OPEs常作为聚氨酯泡沫(PUF)中的阻燃剂,而非氯化OPEs则被广泛用作PVC和PUF中的增塑剂[48]。由此可知,灰尘中DEHP和OPEs可能具有共同来源。此外,TCEP由于其致癌性已逐渐被TCIPP和TDCIPP替代,并在欧盟、美国等多个地区被禁用,但在我国仍在使用且没有任何管控措施[48]。本研究中在所有样品中检出TCEP,且其对OPEs总浓度的平均贡献达到(15.6±18.5)%,值得进一步关注。

本研究中PAHs的浓度水平(中值:2.0 μg·g-1)与广州地区的浓度(2.17 μg·g-1)[7]相当。本研究发现,灰尘中的PAHs以菲为主,这与在广州[7]、大连和通辽[47]地区的研究结果具有一致性。据报道,在亚洲,交通排放、烹饪和生物质燃烧是PAHs的主要来源,室内烹饪、取暖和吸烟活动则会直接加重增加室内PAHs污染[49]。通常低环PAHs(2~3环)来源于石油污染和木柴、煤等在低中温度燃烧,高环PAHs(4~6环)主要来源于化石燃料的高温燃烧[50]。本研究结果发现灰尘中的PAHs以低环为主,推测室内灰尘中PAHs主要来自烹饪等室内源。

3.2 卧室灰尘中SVOCs的健康风险评价

本研究从筛查出的85种SVOCs中,选取38种检出率>10%的SVOCs进行了健康风险评价。结果表明,所有检出SVOCs对成人均无非致癌风险。然而对幼儿来说,苯乙烯化苯酚、DEHP、肉豆蔻酸和硬脂醇的暴露会对0~2岁的幼儿造成一定程度的非致癌风险(HI>0.01)。幼儿的非致癌风险主要是由室内灰尘摄入所导致。幼儿暴露于灰尘中SVOCs的健康风险大于成人的主要原因是:幼儿单位体质量的摄入比成人多,且具有相对频繁的爬行和手对口的行为[51-52]。本研究首次发现室内环境中苯乙烯化苯酚对人体健康造成潜在风险。苯乙烯化苯酚在橡胶中应用广泛,也经常在室内灰尘中检出,但关于它的毒性数据非常缺乏。由于毒性数据的缺乏,本研究中采用QSAR预测的RfD值,评价了其非致癌风险,这可能导致低估或高估实际风险。因此,有必要继续关注室内灰尘中苯乙烯化苯酚对人体健康的风险。此外,研究表明DEHP具有生殖和发育毒性,产前暴露于DEHP可能会增加儿童行为和情绪问题[53]。幼儿正处于生长发育的关键阶段,需要进一步关注室内SVOCs对幼儿的健康风险。

室内灰尘中2种PAHs(荧蒽和芘)对人群的致癌风险,超过了US EPA推荐的致癌风险的可接受水平(10-6)。本研究在灰尘中发现荧蒽和芘是主要的致癌风险来源,它们属于高环PAHs,毒性更大。尽管灰尘中含量更丰富的低环PAHs显示出的致癌风险可忽略,但考虑到PAHs之间的协同作用[54],灰尘中PAHs的联合致癌风险可能会更高。需要进一步关注室内PAHs污染。

本研究通过在室内灰尘中筛查895种SVOCs的存在水平和健康风险,发现了6种SVOCs对人体健康具有潜在危害。然而,本研究仍存在一定的局限性:灰尘样本数量较少,无法较为全面地反映我国家庭灰尘中SVOCs的污染状况,未来研究需要进一步扩大样本量;部分SVOCs的RfD和CSF是通过QSAR模型预测得到,人群暴露于SVOCs的实际健康风险可能被高估或低估;筛查室内SVOCs的健康风险时,未考虑检出的复合污染物的潜在相互作用和联合毒性效应,风险结果存在一定的不确定性。因此,仍需进一步开展研究关注室内SVOCs污染对人体健康的风险。

[1] 段小丽.中国人群暴露参数手册[M].北京: 中国环境出版社, 2013: 269-271

Duan X L.Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population[M].Beijing: China Environmental Science Press, 2013: 269-271(in Chinese)

[2] World Health Organization.Household air pollution and health[EB/OL].(2021-09-22)[2022-03-26].https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health

[3] Lucattini L, Poma G, Covaci A, et al.A review of semi-volatile organic compounds(SVOCs)in the indoor environment: Occurrence in consumer products, indoor air and dust[J].Chemosphere, 2018, 201: 466-482

[4] Sedha S, Lee H, Singh S, et al.Reproductive toxic potential of phthalate compounds—State of art review[J].Pharmacological Research, 2021, 167: 105536

[5] Katsikantami I, Sifakis S, Tzatzarakis M N, et al.A global assessment of phthalates burden and related links to health effects[J].Environment International, 2016, 97: 212-236

[6] Poursafa P, Moosazadeh M, Abedini E, et al.A systematic review on the effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on cardiometabolic impairment[J].International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2017, 8: 19

[7] Zhang Y J, Huang C, Lv Y S, et al.Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure, oxidative potential in dust, and their relationships to oxidative stress in human body: A case study in the indoor environment of Guangzhou, South China[J].Environment International, 2021, 149: 106405

[8] Idowu O, Semple K T, Ramadass K, et al.Beyond the obvious: Environmental health implications of polar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons[J].Environment International, 2019, 123: 543-557

[9] Araki A, Saito I, Kanazawa A, et al.Phosphorus flame retardants in indoor dust and their relation to asthma and allergies of inhabitants[J].Indoor Air, 2014, 24(1): 3-15

[10] Zhu Q Q, Jia J B, Zhang K G, et al.Phthalate esters in indoor dust from several regions, China and their implications for human exposure[J].The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 652: 1187-1194

[11] Hu Q P, Xu L, Liu Y, et al.Co-occurrence and distribution of organophosphate tri-and di-esters in indoor dust from different indoor environments in Guangzhou and their potential human health risk[J].Environmental Pollution, 2020, 262: 114311

[12] Arnold K, Teixeira J P, Mendes A, et al.A pilot study on semivolatile organic compounds in senior care facilities: Implications for older adult exposures[J].Environmental Pollution, 2018, 240: 908-915

[13] Kadokami K, Tanada K, Taneda K, et al.Novel gas chromatography-mass spectrometry database for automatic identification and quantification of micropollutants[J].Journal of Chromatography A, 2005, 1089(1-2): 219-226

[14] Li X H, Tian T, Shang X C, et al.Occurrence and health risks of organic micro-pollutants and metals in groundwater of Chinese rural areas[J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 2020, 128(10): 107010

[15] Duong H T, Kadokami K, Trinh H T, et al.Target screening analysis of 970 semi-volatile organic compounds adsorbed on atmospheric particulate matter in Hanoi, Vietnam[J].Chemosphere, 2019, 219: 784-795

[16] United States Environmental Protection Agency.Guidelines for exposure assessment[R].Washington DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1992

[17] United States Environmental Protection Agency.Risk-assessment guidance for Superfund.Volume 1.Human health evaluation manual.Part A.Interim report(Final)[R].Washington DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1989

[18] United States Environmental Protection Agency.Integrated Risk Information System[DB/OL].[2022-03-26].https://www.epa.gov/iris

[19] United States Environmental Protection Agency.The Risk Assessment Information System[DB/OL].[2022-03-26].https://rais.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/tools/TOX_search?select=chemtox

[20] Wignall J A, Muratov E, Sedykh A, et al.Conditional toxicity value(CTV)predictor: An in silicoapproach for generating quantitative risk estimates for chemicals[J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 2018, 126(5): 057008

[21] Ramos R L, Moreira V R, Lebron Y A R, et al.Phenolic compounds seasonal occurrence and risk assessment in surface and treated waters in Minas Gerais-Brazil[J].Environmental Pollution, 2021, 268(Pt A): 115782

[22] Bai L, Chen W Y, He Z J, et al.Pollution characteristics, sources and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM2.5in an office building in northern areas, China[J].Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020, 53: 101891

[23] United States Environmental Protection Agency.Supplemental guidance for developing soil screening levels for superfund sites[R].Washington DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2002

[24] Doyi I N Y, Isley C F, Soltani N S, et al.Human exposure and risk associated with trace element concentrations in indoor dust from Australian homes[J].Environment International, 2019, 133: 105125

[25] United States Environmental Protection Agency.Exposure factors handbook chapter 16(activity factors)[R].Washington DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2011

[26] Boor B E, Spilak M P, Laverge J, et al.Human exposure to indoor air pollutants in sleep microenvironments: A literature review[J].Building and Environment, 2017, 125: 528-555

[27] Yang C Q, Harris S A, Jantunen L M, et al.Phthalates: Relationships between air, dust, electronic devices, and hands with implications for exposure[J].Environmental Science &Technology, 2020, 54(13): 8186-8197

[28] Bi C Y, Maestre J P, Li H W, et al.Phthalates and organophosphates in settled dust and HVAC filter dust of US low-income homes: Association with season, building characteristics, and childhood asthma[J].Environment International, 2018, 121: 916-930

[29] Huang C N, Chiou Y H, Cho H B, et al.Children’s exposure to phthalates in dust and soil in Southern Taiwan: A study following the phthalate incident in 2011[J].Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 696: 133685

[30] Tang B, Christia C, Malarvannan G, et al.Legacy and emerging organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in indoor microenvironments from Guangzhou, South China[J].Environment International, 2020, 143: 105972

[31] Li X, Zhang W P, Lv J P, et al.Distribution, source apportionment, and health risk assessment of phthalate esters in indoor dust samples across China[J].Environmental Sciences Europe, 2021, 33(1): 1-14

[32] Kashyap D, Agarwal T.Concentration and factors affecting the distribution of phthalates in the air and dust: A global scenario[J].The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 635: 817-827

[33] 程玲珑, 李杏茹, 徐小娟, 等.唐山市大气气溶胶中正构烷烃污染特征及来源分析[J].环境化学, 2016, 35(9): 1808-1814

Cheng L L, Li X R, Xu X J, et al.Pollution characteristics and source analysis of n-alkanes in atmospheric aerosol of Tangshan[J].Environmental Chemistry, 2016, 35(9): 1808-1814(in Chinese)

[34] Fiume M, Bergfeld W F, Belsito D V, et al.Final report on the safety assessment of sodium cetearyl sulfate and related alkyl sulfates as used in cosmetics[J].International Journal of Toxicology, 2010, 29(Suppl.3): 115S-132S

[35] Api A M, Belsito D, Biserta S, et al.RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, 1-nonanol, 2, 4, 6, 8-tetramethyl-, acetate, CAS Registry Number 68922-14-5[J].Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2020, 144: 111640

[36] Subedi B, Sullivan K D, Dhungana B.Phthalate and non-phthalate plasticizers in indoor dust from childcare facilities, salons, and homes across the USA[J].Environmental Pollution, 2017, 230: 701-708

[37] Qi Y Y, He J H, Li Y F, et al.A novel treatment method of PVC-medical waste by near-critical methanol: Dechlorination and additives recovery[J].Waste Management, 2018, 80: 1-9

[38] Meng Z R, Gao X, Yu H F, et al.Compatibility of rubber stoppers for recombinant antitumor-antivirus protein injection by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry[J].Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2019, 9(3): 178-184

[39] Levasseur J L, Hammel S C, Hoffman K, et al.Young children’s exposure to phenols in the home: Associations between house dust, hand wipes, silicone wristbands, and urinary biomarkers[J].Environment International, 2021, 147: 106317

[40] 董林娟, 王孟, 石钰.塑料鞋材中壬基酚和壬基酚聚氧乙烯醚的检测[J].塑料科技, 2021, 49(11): 101-105

Dong L J, Wang M, Shi Y.Determination of nonylphenol and nonylphenol polyoxyethylene ether in plastic shoe materials[J].Plastics Science and Technology, 2021, 49(11): 101-105(in Chinese)

[41] Kubwabo C, Rasmussen P E, Fan X H, et al.Simultaneous quantification of bisphenol A, alkylphenols and alkylphenol ethoxylates in indoor dust by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and a comparison between two sampling techniques[J].Analytical Methods, 2016, 8(20): 4093-4100

[42] Kanazawa A, Saito I, Araki A, et al.Association between indoor exposure to semi-volatile organic compounds and building-related symptoms among the occupants of residential dwellings[J].Indoor Air, 2010, 20(1): 72-84

[43] Lu X M, Chen M J, Zhang X L, et al.Simultaneous quantification of five phenols in settled house dust using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J].Analytical Methods, 2013, 5(19): 5339-5344

[44] 张金龙, 陈墨雨.苯乙烯化苯酚的合成研究[J].精细石油化工进展, 2009, 10(1): 51-52, 55

Zhang J L, Chen M Y.Synthesis of styrenated phenol[J].Advances in Fine Petrochemicals, 2009, 10(1): 51-52, 55(in Chinese)

[45] Chen M Q, Jiang J Y, Gan Z W, et al.Grain size distribution and exposure evaluation of organophosphorus and brominated flame retardants in indoor and outdoor dust and PM10from Chengdu, China[J].Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 365: 280-288

[46] Peng C F, Tan H L, Guo Y, et al.Emerging and legacy flame retardants in indoor dust from East China[J].Chemosphere, 2017, 186: 635-643

[47] Yang Y, Wang Y, Tan F, et al.Pet hair as a potential sentinel of human exposure: Investigating partitioning and exposures from OPEs and PAHs in indoor dust, air, and pet hair from China[J].The Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 745: 140934

[48] Hou M M, Shi Y L, Na G S, et al.A review of organophosphate esters in indoor dust, air, hand wipes and silicone wristbands: Implications for human exposure[J].Environment International, 2021, 146: 106261

[49] Ma Y N, Harrad S.Spatiotemporal analysis and human exposure assessment on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor air, settled house dust, and diet: A review[J].Environment International, 2015, 84: 7-16

[50] 李法松, 韩铖, 周葆华, 等.安徽省室内降尘中多环芳烃分布及来源解析[J].中国环境科学, 2016, 36(2): 363-369

Li F S, Han C, Zhou B H, et al.Distribution and source analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor dust from Anhui Province, China[J].China Environmental Science, 2016, 36(2): 363-369(in Chinese)

[51] Selevan S G, Kimmel C A, Mendola P.Identifying critical windows of exposure for children’s health[J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 2000, 108(Suppl.3): 451-455

[52] Moya J, Phillips L.A review of soil and dust ingestion studies for children[J].Journal of Exposure Science &Environmental Epidemiology, 2014, 24(6): 545-554

[53] Yoon H, Kim T H, Lee B C, et al.Comparison of the exposure assessment of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate between the PBPK model-based reverse dosimetry and scenario-based analysis: A Korean general population study[J].Chemosphere, 2022, 294: 133549

[54] Staal Y C, Hebels D G, van Herwijnen M H, et al.Binary PAH mixtures cause additive or antagonistic effects on gene expression but synergistic effects on DNA adduct formation[J].Carcinogenesis, 2007, 28(12): 2632-2640